“I would rather die upon yonder gallows than to live in slavery.”

Sam Sharpe wrote these words in a letter to the British Parliament from his jail cell in Jamaica. Sharpe, a Baptist deacon and lay preacher, faced execution for organizing and leading a rebellion of 60,000 enslaved persons — the largest such revolt in the British Caribbean.

The rebellion began the day after Christmas in 1831 and brought about the end of slavery in the empire. It became known as the Baptist War.

Sharpe was born in 1801 to an enslaved mother. She was one of 300,000 Africans in Jamaica laboring on sugar cane plantations to satisfy the British sweet tooth. The enslaved outnumbered the white plantocracy in Jamaica 12 to 1.

Portrait of Sam Sharpe by Barrington Watson

Plantation owners resorted to extreme measures to maintain control. An eyewitness declared, “No country excels (Jamaica) in a barbarous treatment of slaves, or in the cruel methods they put them to death.” Baptist abolitionist Martha Gurney saw men forced to work wearing muzzles to keep them from eating and 56-pound weights to keep them from escaping.

The first Baptist church

George Liele, the first ordained African American Baptist preacher, planted the first Baptist church in Jamaica. Freed by his owner to serve God, Liele was commissioned by Georgia Baptists and sent as a missionary to the Black residents of Savannah, Ga. When the British left America in 1783, Liele went with them to Jamaica rather than risk re-enslavement in the American South.

George Liele

While in Jamaica, he baptized hundreds of enslaved Africans and organized them into Baptist congregations.

“It’s no wonder enslaved people saw in Jesus one of their own whose experience of oppression was analogous, and indeed synonymous to their own,” said Professor Anthony Reddie of Oxford University.

Fearing an uprising, the white Jamaican authorities prohibited Christian preaching and teaching on penalty of death to enslaved persons, which they zealously enforced. The predominantly Black Jamaican Baptists refused to capitulate. Instead, they wrote to the Baptist Missionary Society in England and requested help building chapels and setting up mission schools.

The BMS sent several missionaries to Jamaica but refused to openly support emancipation. Mission schools used the Bible to teach enslaved children and adults, including Sam Sharpe, how to read.

“In the reading of the Bible, (Sharpe) gained a sense of who he is as a man before God and before the world.”

“In the reading of the Bible, (Sharpe) gained a sense of who he is as a man before God and before the world,” said Rosemarie Davidson-Gotobed, founder of the Sam Sharpe Lecture. “And also, a realization that his enslaved state was not the will of God. Nor was it the will of God for people to be slave holders. So, his heart was not just for his fellow enslaved people but for the people who were enslaving them.”

Sam Sharpe ordained

Noticing his passion for the Bible, Burchell Baptist Church in Montego Bay ordained Sam Sharpe as a deacon. Unlike other denominations, deacons in Jamaica’s Baptist churches had an enormous amount of autonomy and responsibility. The pastor of Burchell Baptist Church, British missionary Thomas Burchell, often was away so Sharpe conducted the worship services and ran the church in his absence. He also traveled to other local parishes speaking about the injustices of slavery and sharing the gospel, which he believed promised freedom.

“Sam Sharpe is saying, ‘This condition you have me in is a contradiction in terms. I cannot be a Christian and be a slave,’” explained Reddie. “He is making a plea for what we now call Black Liberation Theology. God is not on the side of oppressive structures.”

Sharpe’s own situation was not as dire as those faced by most enslaved persons in Jamaica. During his imprisonment, he reportedly told Henry Bleby, a Methodist missionary, he had no complaint against his owners. But based on what he read in the Bible, white men had no right to hold Black men in bondage just as Black men had no right to enslave white men.

Reddie explains: “Sam Sharpe didn’t hate anyone. He loved justice and hated oppression.” So, Sharpe devised a plan to end chattel slavery in Jamaica.

Illustration of George Liele preaching in Jamaica.

The ‘rebellion’

“It’s called a rebellion, but what he initially had said was that ‘We are people who work hard, and we should be paid for our work. So, after the Christmas break, don’t go back to work.’ (It was) basically a strike,” said Davidson-Gotobed.

The plan was for the slaves to refuse to harvest the ripe sugar cane until the plantation owners met their demands for more time off and pay at “half the going wage rate.” No one would be harmed and nothing destroyed, if the plantocracy complied. However, if plantation owners tried to force them to work without pay, then Sharpe and his followers vowed to fight for their freedom.

On Christmas Day, Sharpe met with leaders from other plantations to finalize details for the strike. Tensions were running high in the community. Some believed the Parliament in England had outlawed slavery, and that Jamaica’s white leaders were hiding emancipation from their Black workers. There were even rumors that plantation owners were plotting to kill the men and keep the women and children enslaved. When the St. James Militia attempted to force Kensington strikers back to work the evening of December 27, they set fire to the “trash house,” a shed used for drying sugar cane.

Sam Sharpe

Because of its elevated position, the Kensington trash house served as a beacon to other estates on the island whose enslaved lit their own sheds in response. Seeing these beacons across the island, Sharpe and his followers knew peaceful resistance was no longer possible. It was time to fight.

The rebels’ Black Regiment achieved a few early victories over the local militia. In a public proclamation, the Jamaican government promised amnesty for those who would surrender and death to any helping the rebels.

“I think it shows that the authorities had been shaken by the event,” said Daniel Gilfoyle, records specialist at the National Archives in England.

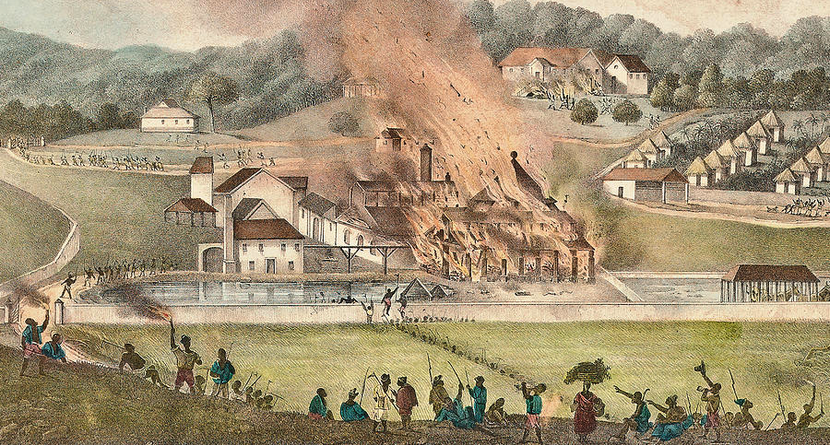

A second proclamation offered a reward of $300 for the capture of Sam Sharpe, referred to as the “Preacher to the Rebels.” During the rebellion, he went from plantation to plantation encouraging the enslaved to join the uprising. When three British Man ’O Wars arrived in Montego Bay, Sharpe’s followers realized they were no match for the military. They turned their attention to destroying the infrastructure of sugar cane production, its factories, wharves and water canals. A later government report estimated the total damage done at £1,154,589 (£106,804,144.72 in 2023).

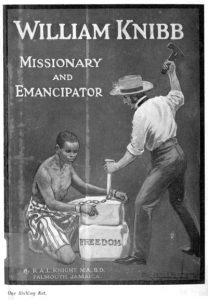

When the governor declared martial law, plantation owners and Anglican clergy quickly formed the Colonial Church Union, a vigilante group whose objective was “to wipe the non-conformist preachers off the face of the earth.” During the chaos of the rebellion, the CCU burned down a dozen Baptist chapels and for three days stoned the house of Baptist missionary William Knibb. Some sources claim the CCU threatened to tar and feather him if he ventured outside. The authorities jailed Knibb and Thomas Burchell and charged them with treason for their connections to the rebels. A court found both innocent and later released them.

“Those in charge, slave owners themselves, executed 300 participants.”

The Baptist War lasted for more than a week before colonial authorities gained control of the island. Sam Sharpe and 500 other enslaved Jamaicans were captured and tried in a “slave court.” Retribution was swift. Those in charge, slave owners themselves, executed 300 participants. Some were beheaded and their heads placed atop poles around the sugar cane plantations.

One hundred and sixty enslaved people were sentenced to flogging or the workhouse. Those who were flogged were given anywhere from 50 to 500 lashes.

“Eliza James and Susan James were accused of stealing a jug of rum during the insurgency while the building was on fire. They were given quite severe sentences, (200) lashes,” said Gilfoyle. The court documents show “the very severe attitude which the authorities took toward the insurgency.”

Destruction of the Roehampton Estate, January 1832 (Public domain image, Painting by Adolphe Duperly)

Sam Sharpe’s trial

Sam Sharpe’s trial was held April 19. The slave court found him guilty of “rebellious conspiracy and administering unlawful oaths.”

“Sam Sharpe himself was given the offer to not rebel and we will spare you and he said he would rather die on the gallows than live another day as a slave,” Davidson-Gotobed said. A month later, on May 23, Sharpe swiftly mounted the gallows’ steps and said to the crowd, “I will soon appear before a judge that is greater than all. Let me beg you, my brethren, to attend to your Christian duties, for it is the only way for you to go to salvation. I now bid you farewell.”

The authorities buried Sharpe’s body in the sands at Montego Bay Harbor, the “cemetery” for criminals. Knibb later moved Sharpe’s bones and interred them in a place of honor beneath the pulpit of the rebuilt Burchell Memorial Baptist Church.

Telling the story in Britain

Just as the enslaved Jamaican Baptists had called for missionaries to come to the island, after Sharpe’s death they asked Knibb to return to the United Kingdom and plead the case for emancipation before the British public. Speaking to the congregation at Spa Fields Chapel he said, “I call upon you all by the sympathies of Jesus, whose mission was, and is, to bind up the brokenhearted, and to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to them that ‘are bound.’ Lord, open the eyes of Christians in England to see the evils of slavery and banish it forever from the earth.”

Hearing Knibb speak about atrocities in Jamaica, the Baptist Mission Society reversed its policy of remaining politically neutral and supported the anti-slavery movement.

Knibb also testified before both Houses of Parliament about the rebellion and its aftermath. His testimony, along with the dedication shown by the Jamaican rebels, moved Parliament to pass the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. It granted enslaved people in the Caribbean emancipation after they served an apprenticeship.

Knibb also testified before both Houses of Parliament about the rebellion and its aftermath. His testimony, along with the dedication shown by the Jamaican rebels, moved Parliament to pass the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. It granted enslaved people in the Caribbean emancipation after they served an apprenticeship.

However, “when the powers within Britain met to discuss so called Black freedom, not one Black person was present when the conversation was taking place about them. About them, without them,” noted Reddie. This lack of representation led to abuses by plantation owners, who charged workers inflated prices for their apprenticeships. Lobbying by Knibb and other abolitionists ended the apprenticeship scheme, and in 1838 enslaved Jamaicans finally received their full emancipation.

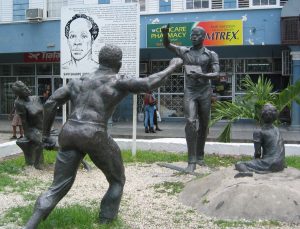

The government of Jamaica officially proclaimed Sam Sharpe a national hero in 1975 and renamed the site where he was executed Sam Sharpe Square. A bronze statue of Sharpe preaching from the Bible was added to the area in 1983.

Outside of Jamaica, Sharpe remained little more than a footnote in Baptist history until 2007. In a sermon, Karl Henlin, president of the Jamaican Baptist Union, challenged British Baptists to offer a “full apology” for their past involvement in the salve trade. Only then, said Henlin, “the forgiveness that is on offer can be appropriated, the healing made complete and the chapter closed.”

“Although he was an enslaved person, he knew he was free.”

The following year, a small delegation from Baptist Union of Great Britain traveled to Jamaica and delivered the apology in person. In 2010, both the Jamaican and British Baptist Unions partnered with Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture to host the first International Conference on Sam Sharpe. This successful conference grew into the Sam Sharpe Project and the annual Sam Sharpe Lecture.

“It’s a platform to talk about what does this legacy mean in various aspects of our lives in this country,” Davidson-Gotobed said. “What does it mean to be justified in your rebellion? What does it mean to be community? So those are the aspects we hope to provide conversations for through the lectures.”

Statue of Samuel Sharpe in Montego Bay, Jamaica (Wikidata)

Each year, the Sam Sharpe Lecture is held at a different location with a different presenter. In 2023, Anthony Reddie delivered the lecture, “From Sam Sharpe to Black Lives Matter: The Continued Struggle for Black Agency and Self-Determination,” at the University of Roehampton’s Whitelands College.

“We are not living with the privations and the restrictions that Sam Sharpe was wrestling with, and yet there’s still the ongoing battle which we need to continue to wage, which is the right for black agency and self-determination,” he said. “The gift of faith is the gift of transcendence. It’s the gift to believe that you are more than whatever a society and its strictures and its boundaries are placed upon you. That was Sam Sharpe’s imagination. Although he was an enslaved person, he knew he was free. So we have to start with the assumption that we are free already but our activism is in order to make good on our promise.”

There is still much work to be done. But Sam Sharpe and William Knibb show what is possible when Christians preach and live with conviction the gospel that sets all people free.