Editor’s note: This is the first opinion piece in a new series on religious liberty authored by BJC Fellows and made possible by a grant from the Prichard Family Foundation.

Picture yourself in a first grade classroom, one with colored rugs on the floor for circle time and little desks clumped together in groups of four. On the wall, a clock with a silly poem about telling time hangs above a cart full of art supplies. And, next to it, a framed copy — at least 16 by 20 inches — of the Ten Commandments.

Does this seem out of place to you? It certainly is a jarring image for me, especially after all I learned from the BJC Fellows program. Bound by my Catholic faith to recognize and honor the dignity of every person with a particular interest in interfaith collaboration, I was drawn to the work of BJC and the effort they pour into protecting religious liberty for all.

“BJC taught me how to advocate for religious liberty for all because of my Catholic Christian identity, not in spite of it.”

The BJC Fellows program provides a training in Colonial Williamsburg for young professionals to deepen our historical, theological and legal understanding of religious liberty in the United States and how we have a responsibility to use these new skills to advocate for the cause throughout our careers. BJC taught me how to advocate for religious liberty for all because of my Catholic Christian identity, not in spite of it.

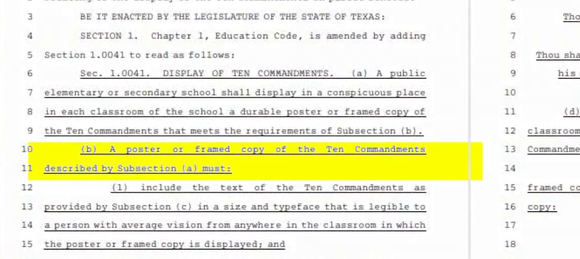

So when I first heard the news about HB 3448/SB 1515, I tuned right into the proposal. On April 5, the Texas State Senate Education Committee held a hearing for this bill, which would require a framed copy or poster displaying the Ten Commandments (King James version) in every public school classroom in the state. The bill specifies the poster must be “in a size and typeface that is legible to a person with average vision from anywhere in the classroom in which the poster or framed copy is displayed; and be at least 16 inches wide and 20 inches tall.”

Public schools would be required to accept any donated posters, and teachers would not be permitted to add any additional content. Texas Senator Phil King, R-Weatherford, introduced this bill and stated, “I think this would be a good, healthy step for Texas to bring back this tradition of recognizing America’s religious heritage. Senate Bill 1515 restores a little bit of those liberties that were lost.”

“Our religious history is a much more complicated story. And the heroes are the ones who recognized the need for both freedom for religion and freedom from religion.”

Senator King, like so many others, seems to believe the myth that the United States was founded as a religious country. My training with BJC taught me our religious history is a much more complicated story. And the heroes are the ones who recognized the need for both freedom for religion and freedom from religion.

That’s what our founders actually wrote into the First Amendment, after all: two different protections for religion. The protection of free exercise keeps the government from unnecessarily interfering with religious practices. This means my public-school first grader can wear a cross around his neck or pray before he eats lunch. The prohibition on an establishment of religion keeps the government from advancing or privileging religion. This means my son’s teacher cannot make him wear a cross necklace or require the whole gaggle of 7-year-olds to pray together during class time. With both protections from the First Amendment in mind, I fear this proposal is sorely out of place.

Britt Luby

In my son’s classroom, his teacher has a colorful poster with the classroom rules. He and his peers are expected to do things like “Listen when your teacher is talking” and “Be kind to others.” They even came up with a few rules to add to the list themselves: “Share your pencils” and “Use walking feet.” These are all age-appropriate expectations for young children sharing space in a public school setting, and he does his best to be a relatively good student. He interrupts his teacher more than I wish he did, and he also gets in trouble for talking too much to his best friend, Buddy.

Imagine another sign on the wall, one that includes, “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his cattle, nor anything that is thy neighbor’s.” Who is this message for, at the end of the day? And why? And who is charged with teaching these kids what all the words even mean? How should his Muslim classmate, Ali, understand this poster? And how should his agnostic teacher?

When referring to our country’s religious heritage, I wonder if Sen. King knows of Thomas Jefferson’s 1799 Letter to Elbridge Gerry, written when Jefferson was vice president. In this note, Jefferson wrote, “I am for freedom of religion, & against all maneuvres to bring about a legal ascendancy of one sect over another.”

The absence of a copy of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms is actually part of America’s historical relationship with church-state separation. The commandments are a religious text, and placing them in a government setting is counterintuitive to what Jefferson hoped this country would offer people of all religious traditions (or those with none at all).

Perhaps Sen. King should read more of Baptist preacher John Leland’s work, especially his 1791 text “The Right of Conscience Inalienable.”

Baptist leaders today continue to preach the same charge. In 2005, Holly Hollman wrote, “Those who share the BJC perspective on religious liberty will continue to promote the Ten Commandments (and other scriptural mandates) in a way that the Bible encourages: by writing them on our hearts, as the prophet Jeremiah instructed.”

For now, because of my identity as a Christian and not in spite of it, that is where I want the Ten Commandments to stay: in my church, in my home, in my heart.

Britt Luby earned a master’s degree in religion (ethics and social theory) from the Graduate Theological Union in conjunction with the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley, Calif. After years of service as a lay Catholic university chaplain, she now works in hospital chaplaincy. She is a member of Daughters of Abraham, an interfaith women’s group. She lives in Fort Worth, Texas. Read more of her writing here.

BJC Fellows come from diverse educational, professional and religious backgrounds to learn in an intensive education program that equips them for advocacy to protect religious liberty. Learn more about the program here.

Related articles:

Robert Jeffress says schools should fight gun violence by teaching the Ten Commandments

New platform of Texas GOP is laced with Christian privilege

Hypocrisy | Opinion by Mark Wingfield