By Bob Allen

A longtime pastor at a D.C.-area evangelical church testified in court May 13 that he did not report crimes alleged in 1992 against a man standing trial this week on charges of sexual abuse, according to a one-time ministerial colleague turned whistleblower attending the weeklong trial in Montgomery County, Md.

Brent Detwiler, who writes a blog devoted to alleged cover-up of child sexual abuse in churches affiliated with Sovereign Grace Ministries, said Tuesday’s testimony by Grant Layman, who stepped down recently after 31 years as a pastor at Covenant Life Church in Gaithersburg, Md., removes any doubt that church leaders conspired to cover up crimes while treating abuse allegations as a matter for private church discipline.

Sovereign Grace Ministries, a church-planting network with Reformed and charismatic theology, is not part of the Southern Baptist Convention, but its co-founder, C.J. Mahaney, is close friends with SBC leaders in a neo-Calvinist movement that goes by names including “young, restless and Reformed.”

Mahaney, now pastor of Sovereign Grace Church in Louisville, Ky., announced last summer that he would not participate in this year’s Together for the Gospel conference that he previously co-sponsored with Southern Seminary President Albert Mohler and Washington pastor Mark Dever, though he apparently attended.

Mohler and Dever were criticized previously for publicly supporting Mahaney amid allegations in a high-profile lawsuit that he conspired with other Sovereign Grace leaders in what media described as the largest evangelical abuse cover-up scandal to date.

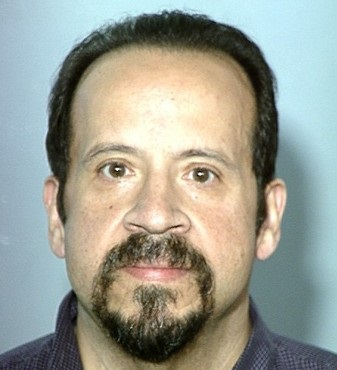

The civil lawsuit was dismissed for legal reasons and is under appeal, but one of a number of alleged pedophiles it names faces criminal charges in Montgomery County Circuit Court. Nathaniel Morales, a former member at the 3,000-member Covenant Life Church, stands accused of molesting numerous boys in the 1980s and 1990s.

The civil lawsuit was dismissed for legal reasons and is under appeal, but one of a number of alleged pedophiles it names faces criminal charges in Montgomery County Circuit Court. Nathaniel Morales, a former member at the 3,000-member Covenant Life Church, stands accused of molesting numerous boys in the 1980s and 1990s.

Detwiler, one of four founders of Sovereign Grace Ministries, broke ties with the movement after challenging Mahaney’s leadership before the SGM board. Mahaney took a leave of absence in 2011 and was later declared fit for ministry by the SGM board.

Mahaney stepped down last year as president of Sovereign Grace Ministries. The board issued a statement of gratitude for his leadership, but Detwiler said it was window-dressing and claimed that Mahaney was asked to resign.

Detwiler said none of the Covenant Life Church pastors or any leaders from Sovereign Grace Ministries have attended Morales’ trial so far.

“I find that utterly reprehensible,” Detwiler wrote. “The entire pastoral staff of Covenant Life Church should have attended the trial to hear the evidence against Morales and against them. Furthermore, they should have been here to support the victims and hear their anguished testimony. Tomorrow, they should be present to beg everyone’s forgiveness and begin the process of public confession, calling C.J. Mahaney to account, and making restitution to the victims.”

Russell Moore, head of the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, said at a recent conference on sexuality that church leaders who suspect abuse have an obligation both to contact legal authorities and to address it internally through church discipline.

“If someone comes and says ‘I have been abused sexually’ or ‘I know someone who’s been abused sexually,’ you have to first of all recognize that there are two authorities at work here, and both of them need to be involved,” Moore said.

“Caesar has a responsibility to deal with this at the civil level. The church has a responsibility to deal with this at the ecclesial level. You immediately call the police. Even if you don’t know whether this is true or not, you don’t know whether or not this has actually happened, you call the police and you say, ‘Caesar has a responsibility, the government has a responsibility, to investigate this.’

“You also … though, can’t simply say, ‘Well, we have sex abuse happening and that’s a civil issue so the civil state deals with it.’ They do, but you also come in and deal with it in terms of church discipline, which means that you’re saying if this is someone who is sexually predatory in our congregation, we are also going to deal with it at the level of church discipline, and we’re going to deal with this very, very seriously.”

Amy Smith, Houston representative for the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, said when allegations of abuse arise, the first and foremost concern should be for the victims.

“There should not be any distinction of the ‘civil level’ and ‘ecclesial level’ when it comes to reporting alleged crimes,” she said. “The church is not above or outside of the law.”

Moore said that given the number of Americans who have been sexually abused, it’s likely that every church includes someone who has been victimized.

“Some of them are battling with all sorts of psychological issues that come with people saying to them or implying to them that somehow they were at fault or at blame,” he said. “You need to eradicate that and say, ‘No, you’re not to blame for this. We’re ministering to you as somebody who was a victim, who is continually a victim, of what has been done to you.’”

Christa Brown, an abuse survivor and longtime victims’ advocate, said the reality in many Southern Baptist churches is that those who report clergy sex abuse are demonized, churches typically keep quiet about it and predatory clergy hop from church to church because the denomination lacks any cooperative mechanisms to track them.

Brown worked unsuccessfully in 2006 to persuade SBC leaders to create a database of credibly accused predators and establish an independent panel to receive and evaluate reports of clergy abuse.

“Until Southern Baptist leaders can honestly acknowledge the wrong in what they have done in the past, and until they will hold accountable those pastors who have covered up for clergy sex crimes, no one should expect the future in Baptistland to be any different,” Brown said.