Africans look with dismay on the parting gift U.S. President Donald Trump has given them: On the last day of 2020, Trump extended the U.S. government’s ban on green cards and work visas, which his administration imposed in April last year as the coronavirus pandemic swept the globe.

The new order, like the first one, was meant to ensure that American workers didn’t lose jobs to foreign nationals desiring to migrate to the United States, the administration said. But in Africa, even before the coronavirus outbreak, Trump’s immigration policies had been particularly felt.

Migration from Africa to America

Over the decades, America, with its prospect of a better life, has been a choice destination for many leaving home around the globe, including large numbers of Africans. But Trump, who campaigned on an “America First” anti-immigration policy, made securing an American visa a more difficult process than it had been. Even some Africans who relied on naturalized family members in the U.S. to assist them to travel to the country saw their dreams upended.

While global attention has focused on the U.S.-Mexico border, Africans have been impeded by Trump’s immigration policies as well.

While much global attention has focused on the U.S.-Mexico border, where a mass of mainly Latin American migrants seek refuge in the U.S., Africans at home or in the U.S. have been impeded by Trump’s immigration policies as well.

Early in his administration, prospective travelers from three African countries — Sudan, Libya and Somalia — had their travel plans truncated by Trump’s executive order that banned travel from seven countries from entering the U.S. These were among the countries he later called “shithole countries.”

Then in January 2020 the Trump administration placed visa restriction on six countries, four of which are in Africa: Eritrea, Nigeria, Sudan and Tanzania. The restriction was reportedly imposed as penalty for the failure of the listed countries to meet certain U.S. security and information-sharing standards. The implication was that citizens of those countries are no longer eligible to apply or be sponsored for permanent residency by even their own family members with the right to do so.

According to a 2019 Migration Policy Institute report, “Slightly more than 2 million immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa lived in the United States in 2018.” The report reveals that while this figure represents “just 4.5% of the country’s 44.7 million immigrants, it is a rapidly growing one,” as “between 2010 and 2018, the sub-Saharan African population increased by 52%, significantly outpacing the 12% growth rate for the overall foreign-born population during that same period.”

Prior to this time, the report adds, “there were very few sub-Saharan Africans in the United States … with under 150,000 residents in 1980. Since then, immigrants from some of the largest sub-Saharan countries, such as Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Somalia and South Africa, have settled in the United States. Overall, more than 2 million immigrants have come from the 51 countries that comprise sub-Saharan Africa, making up 84% of the 2.4 million immigrants from the entire African continent. The remainder are from the six countries of North Africa: Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Sudan and Tunisia.”

Making travel to America more difficult

Before the Trump administration’s January 2020 order, the U.S Embassy had cancelled the dropbox visa process in Nigeria, which allowed some visa applicants the option of not appearing in person at the embassy. A statement from the U.S Embassy and Consulate in Nigeria, with the headline, “Indefinite Suspension of ‘Dropbox’ Process for Renewals,” informs that effective May 14, 2019, the U.S Mission to Nigeria would indefinitely suspend interview waivers for renewals, otherwise known as the “Dropbox” process. That meant every visa applicant was to appear in person at the consulate for an interview, a much more laborious process.

Visa applicants from of 23 countries —16 of which are African— must now pay bonds of between $5,000 to $15,000.

Making securing an American visa even more difficult for some Africans was a visa bond pilot program initiated two months ago, which requires nationals of 23 countries —16 of which are African— seeking tourist and business visas, to pay bonds of between $5,000 to $15,000, excluding the visa fee. The U.S. Department of State statement said the increase was meant to serve as a deterrent for countries with high visa overstay in the U.S.

The State Department said the number of “overstays” among non-immigrant visitors had grown from 228,783 in 2015 to 320,086 in 2019. The defaulting African countries listed were Angola, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa), Djibouti, Eritrea, the Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Libya, Mauritania, Papua New Guinea, Sao Tome and Principe, and Sudan.

Long before this disclosure, stringent visa policies resulted in a high decline rate for African applicants seeking U.S. visas. Relating specifically to Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, a January 2020 report by Quartz, states that “data from the U.S. travel and tourism office shows Nigeria recorded the largest global drop-off in visitors to the U.S. As of October 2019, 34,000 fewer Nigerians traveled to the U.S. compared to the previous year — a 21% drop. After a sustained period of growth between 2011 and 2015, the number of Nigerian visitors to the U.S. started to plateau in 2016 until the big drop-off last year.”

A diplomatic row with Ghana

Ghana also wasn’t spared from Trump’s immigration onslaught. A statement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement showed that 305 Ghanaians were to be removed from the U.S. in 2017, while 243 others were to be deported in 2018. But Ghanaian authorities didn’t fancy the idea. This soon created a diplomatic row as the U.S. State Department decided to restrict entry of top Ghanaian government officials and their families into the country. The face-off lasted until February 2019, when the U.S. Embassy in Ghana announced that the sanction had been lifted. Ghana wasn’t the only country affected. Guinea, Eritrea and Sierra Leone were similarly called out and sanctioned.

Prince Appiah

Prince Appiah, a Ghana journalist, recalls that the issue attracted diverse reactions from Ghanaians.

“Government officials reacted differently from ordinary Ghanaians,” he said. “A good number of top government officials were mad at the U.S. because they (felt they) were working in the interest of (their) people.” Meanwhile, “ordinary Ghanaians were very happy government officials were banned because they felt these officials take advantage of state resources to benefit from opportunities that come with travelling to foreign countries while the underprivileged class who really need the opportunities to change their family fortunes don’t get such privileges.” He added that “it is believed a good number of top officials have their children and family sometimes living and schooling abroad, benefiting from (assumed better) economic and educational systems.”

Generally, Appiah feels that “Trump’s immigration policies didn’t favor Africa and its people,” as “a greater number of people were denied the opportunity to access the economic and educational benefits” in the U.S.

A long history of desperate migration

While that is evidently true, it is also not in doubt that long before Trump came to power, not everyone who applies for a U.S. visa succeeded in getting it. But that doesn’t deter some Africans, particularly the desperate ones seeking to travel abroad, whether to Europe, the Americas, Asia or elsewhere, from seeking other options.

A new born baby girl lays in her mothers’ arms right after being born onboard a Spanish rescue vessel on the Mediterranean Sea, Wednesday, Sept. 6, 2017. A rescued woman from Ghana has given birth to a girl immediately after being rescued while trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea from Libya to Italy on a traffickers’ flimsy dinghy. (AP Photo/Bram Janssen)

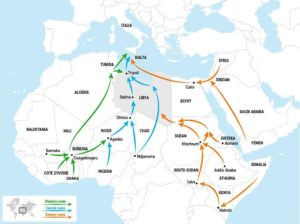

A route often explored by them is the Sahara desert or Sahel region linking countries like Niger Republic and Libya, the latter of which shares a maritime border with countries like Italy. It is the devil’s alternative of a route, not just because of the gangs and human traffickers that operate along the region, but also because of the insufferable nature of the peregrination that may lead to nowhere. But some people, waving aside concerns of the danger, see it as their only way to travel abroad. Some of those who manage to make it beyond Libya to Europe and still have their sights on the U.S. also fancy the Mexican border with the U.S. as an option to reach America.

Bola Olajuwon, a Nigerian development journalist who also covers migration, describes the Niger-Libya route as a smuggling epicenter, made even worse by the absence of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya’s former powerful president, who was killed after the protests that arose from the Arab Spring.

Said Olajuwon: “After the fall of Gaddafi in 2011, long locked smuggling routes between Niger and Libya suddenly reopened, and Agadez, the small desert town of roughly 120,000 inhabitants, became the de facto smuggling capital of the sub-Saharan region. However, owing to a European Union pact with Niger and warlords in Libya, trafficking in humans had reduced drastically and the family business had suffered a serious bash. But the dangerous dimension is that locals and traffickers have taken to smuggling of guns and ammunition” as well as the “sale of Black Africans,” leading to “a booming black market for parts of the human body in the Middle East now.”

Bola Olajuwon

He pointed out that “migration from Nigeria or Africa, in general, has the elements of the good, the bad and the ugly,” and that while movement of people from place to place is as old as human existence, migration, in our time, “has emerged as a major challenge of the 21st century.”

“The bad and the ugly side of migration, which is illegal migration to Europe (a pathway that leads to forced labor, beatings, torture and rape) reached a peak in 2015, when rising numbers of people, from Nigeria and other parts of Africa, arrived in EU countries, traveling across the Mediterranean Sea,” he said.

“EU’s policies to engage with the countries where illegal migrants pass through to Europe, media reports on death and the global outcry over the open sale of migrants as slaves in Libya have assisted in reducing the carnage on Sahara Desert-Agadez and the Libyan-Mediterranean Sea migrants’ routes,” he added. “While the number of migrants to Europe might have reduced, the illegal migrants and traffickers have become daring in their operations.”

Other perils on the journey

According to the International Organization for Migration, “migration should be a choice, not a necessity,” but varied accounts of many African migrants interviewed on their journey experiences over the years along the perilous Sahel route, from Nigeria to Ghana, Liberia, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Eritrea or elsewhere consider it to be both a matter of choice and necessity. Joblessness, poverty, hardship, conflict, religious persecution, insecurity, corruption and embezzlement of state funds by elites are just a few problems cited by many as to why they opted to seek succor elsewhere.

AURELIE BAUMEL, Médecines san Frontières

Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria, for example, which targets both Muslims and Christians, has led to the death of thousands and displacement of millions of people from their homes and created a refugee and humanitarian crisis both within and outside the country in places like Niger Republic, Chad and Cameroon, where the Boko Haram violence is also rife.

Apart from the Boko Haram crisis, Cameroon is also battling with a secessionist struggle by people in the southern part of the country, which on its own had displaced many from their land, leading to a rising refugee rate within and outside the country. And long before now, the Liberian civil war and conflicts in Somalia, Sudan, to mention just these, led to many citizens of the countries seeking asylum in countries like the U.S.

False assumptions taught about migration

There are some, however, who view migration from an ethno-centric standpoint.

“I see the concept of migration as a very interesting part of the African psyche; in that, culturally we are made to believe that one can only be successful to a large extent when an individual moves from his hometown or village to the city,” Appiah said. “So growing up in most parts of Africa, many people grow up looking for greener pastures outside of where they are born.”

Such a mindset “has graduated into not only moving from one’s village to the cities to be ‘successful’ but from Ghana, Nigeria or Africa to Europe or USA to fulfil their dreams and become successful,” he added. “Now the concept of migration has changed from many moving from Ghana or Africa directly to go look for jobs out there in USA, to attending better schools with the belief of securing better job afterward. This has resulted in Ghana or Africa losing many brainy individuals to the USA or the European countries where they find themselves.”

Olajuwon, who noted that Nigeria’s “brain drain escalation reached an alarming rate since the ’80s,” said that “whether through illegal or legal migration, Nigeria and other African countries have lost a significant number of their citizens to other continents over the years.”

With Trump set to leave office in just a matter of days, to be replaced by a man who has vastly different views, many who feel harmed by Trump’s policies may heave a sigh of relief. But Olajuwon believes a return to previous travel and immigration policies shouldn’t absolve the responsibility of African leaders to account for the disenchantment and eagerness of many Africans to relocate abroad.

African leaders should “replicate the better environment in Europe and America in Nigeria and other parts of Africa,” he suggested.

“I know that Africa is progressing, but the growth rate is static and enormous economic, social and political challenges are rampant in most of the countries, Nigeria inclusive. Nigeria and others must tackle poverty, create better and quality education, health and inclusive democracy,” he advised. “Economic transformation and creation of productive employment for young people, containment of clientelism and corruption, improvement of public services — education, health and infrastructure — investment climate, more private and infrastructural investment are key to tackling illegal migration and brain drain.”

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born journalist currently living in Houston.