“Each and every sin in its own unique way is a denial of what is real.” — Fr. Terrance Klein

In my last post, I began to explore the ethics of truth as one finds this theme in the New Testament. My conclusion was that for the New Testament writers overall, spirituality is the core of character, character is the core of action, and one of the most important actions in New Testament terms is “walking in the truth.”

In this post, I want to explore the relationship between truthfulness and humility. My proposal is that living truthfully requires humility before the truth. Not just humility before the Truth, that is, God or Jesus. I really mean humbling oneself before truth itself. The virtue of truthfulness requires the related virtue of humility.

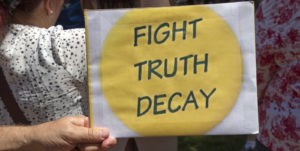

(Bigstockphoto)

I cannot find a direct biblical reference connecting truthfulness and humility. I do, though, see several texts connecting pride and lying. Consider this one: “For the sin of their mouths, the words of their lips, let them be trapped in their pride. For the cursing and lies that they utter, consume them in wrath” (Psalm 59:12-13; Jeremiah 5).

Let me see if I can unpack the connection between truthfulness and humility.

The truth comes to us like that mountain looming before you when you make the turn on the interstate and it’s just there. Truth recognizes and accurately describes the mountain that is there.

It’s so basic. And yet, so often we are unwilling to admit that we see the mountain. As T.S. Eliot has the Archbishop of Canterbury say in “Murder in the Cathedral” — “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.”

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality.”

It is January 2020, and there is a killer disease coming our way. The leaders in understanding this new killer are the scientific specialists in infectious disease. Their job is to recognize, accurately describe and combat this disease, based on the canons of their discipline. The job of politicians is to give a platform to the scientists to offer their best public description of reality, to listen to their recommendations concerning best mitigation, treatment and vaccine development strategies, and to guide communities in developing overall policy responses for the common good.

This activity requires humility in the face of terribly unpleasant reality. We wish there were not a killer disease coming our way, but it is coming. We wish it were not likely to spread in large groups, especially large groups not wearing masks and not keeping their distance from each other, but that is reality. We wish our lives were not going to be disrupted by this disease, but they will be. We will need to respond to reality as we find it.

Bending my will to reality — instead of attempting to redescribe or deny reality so that it fits with my will — requires humility.

This is especially the case when reality, and truthful description of it, is painful or embarrassing.

You are struggling with addiction, but you do not want anyone to know. Your spouse has lost his job, but you are trying to hold the news back as long as possible. You were supposed to pick up Junior from school at 2, but you got busy at work and forgot; you are tempted to say that you got stuck in traffic.

“Truth is greater, and you are lesser.”

But when push comes to shove, you instead recognize that reality is real and you must tell the truth about it. Truth is greater, and you are lesser. You humble yourself before reality and tell the truth — even if the consequences of doing so are far from sweet for you.

There is good reason why in many religious traditions, a basic claim is that the Divine creates, defines and grounds reality. This may be one implication of the mysterious revelation of the Divine Name in Exodus 3:14 — “I am who I am/what I am/what I will be.”

To submit oneself to God is very much akin to, or part of, submitting oneself to reality and, therefore, to truth. The same fundamental virtue inculcated in the spiritual life — humble submission before God — is required in relation to truth itself.

What we saw in the United States over the last four years was a president who lacked the humility — or is it the mental health? — to humble himself before reality. Instead, reality needed to be redescribed, redefined and reconfigured so that under no circumstances would a description of reality reflect badly on Donald J. Trump.

In many areas this could seem merely amusing. Do you remember when Trump misspoke (actually, mis-tweeted) about the potential of Hurricane Dorian reaching as far north as Alabama, and the National Weather Service corrected him? But he refused to admit he had been wrong. A few days later, in view of reporters, he had an aide bring him the official projected map of the path of the hurricane from the National Weather Service. Someone had used a black Sharpie to draw a big circle extending the possible path into Alabama. So he was right all along! When asked later who had drawn in Sharpie on an official weather map, the president purported not to know. A few days later the Washington Post reported that aides had revealed that the president, who always carries personalized black Sharpie pens, was himself the culprit.

“Humility is the virtue that enables submission to truth.”

Lies upon lies upon lies. All because the president was unwilling, or unable, to humble himself before the truth, even this silly little mistake.

Reality exists. Truthfulness is (in this dimension) making statements that correspond with reality. Humility is the virtue that enables submission to truth. When my will bumps up against reality, I defer humbly to reality. This does not mean that I might not undertake every effort to change aspects of reality that are changeable, so that bad realities eventually might become better ones. But in the meantime, I describe reality for what it is.

Humility and truthfulness are inextricably related virtues. Conversely, pridefulness and lying are inextricably related vices.

David Gushee serves as Distinguished University Professor of Christian Ethics and director of the Center for Theology and Public Life at Mercer University. He is the past-president of both the American Academy of Religion and Society of Christian Ethics. He is an author or editor of 25 books. His most recognized works include Righteous Gentiles of the Holocaust, Kingdom Ethics, The Sacredness of Human Life, and Changing Our Mind. He earned the Ph.D. from Union Seminary. He and his wife, Jeanie, live in Atlanta.

David Gushee serves as Distinguished University Professor of Christian Ethics and director of the Center for Theology and Public Life at Mercer University. He is the past-president of both the American Academy of Religion and Society of Christian Ethics. He is an author or editor of 25 books. His most recognized works include Righteous Gentiles of the Holocaust, Kingdom Ethics, The Sacredness of Human Life, and Changing Our Mind. He earned the Ph.D. from Union Seminary. He and his wife, Jeanie, live in Atlanta.

Other articles in this series: