Ukraine is a fascinating nation, the second largest in Europe by land area and the eighth most populous, after Russia. Although it is the poorest country in Europe, its extensive farmlands enable it to be one of the largest wheat producers in the world, annually exporting about 24 million metric tons, grown in the southeastern region where Russian troops already have invaded.

With a history that dates back thousands of years, Ukraine primarily exhibits traditional, if not modest, customs. Its art, music, literature and architecture are influenced both by its geographic neighbors and its religious traditions.

Concerning the religious affiliation of the more than 44 million Ukrainians, a 2018 survey conducted by the Razumkov Centre, a nongovernmental think tank founded in Kyiv in 1994, discovered that 67.3% claim to be members of one of several branches of the Orthodox Christian Church. Another 10.2% of the population are either Greek rite or Latin rite Catholics. Another 9.9% say they are also Christian, either identifying as one of several sects of Protestants or as believers who identify with no particular denomination. Followers of Judaism and Islam comprise 0.4% of the population. Hindus, Buddhists and Pagans make up about 0.1% of the Ukrainian citizenry each.

Followers of these religions differ dramatically in their doctrines. Some laypersons may assume that all religions have a sacred book, or worship a divine being, or have a set of commandments. But these specific characteristics do not define every religion, even all of those practiced in Ukraine.

It is more accurate to speak of a much broader list of traits that are commonly found in religions, including all the ones celebrated there. According to Michael Molloy in Experiencing the World’s Religions: Tradition, Challenge, and Change, these eight more general elements are present to some degree in what is ordinarily referred to as “religions.” They feature 1) a belief system; 2) a community; 3) central myths; 4) rituals; 5) ethics; 6) characteristic emotional experiences; 7) material expressions; and 8) sacredness.

The religions of Ukrainians are very different based upon their doctrines, or beliefs, but are strikingly similar in their ethics, or behaviors. One moral constant across the religious spectrum is to make and maintain peace.

“The religions of Ukrainians are very different based upon their doctrines, or beliefs, but are strikingly similar in their ethics, or behaviors. One moral constant across the religious spectrum is to make and maintain peace.”

It is thus reasonable to conclude that regardless of their religious identity or practice, some 90% of the populace of Ukraine values peaceful coexistence and desires it for themselves and their families. Followers of each spiritual tradition pray that their sacred sites and spaces will remain undamaged and undefiled.

Despite sectarian distinctions, they share a pride in their nation’s freedom and feel a strong impulse to defend it against foreign aggression, whether or not their religious teachings permit them to take up arms or commit violence.

Fathers and mothers collectively fear for the safety of their children and want to shelter them from harm and the trauma of war. All these Ukrainians cannot comprehend that their peaceful lives and ordinary activities suddenly have been threatened and are under attack.

To provide a more informed picture of who these Ukrainians of various faiths are — what they believe and how those beliefs lead them to treasure peace — I have turned to a group of my personal friends who are followers of the multiple religious traditions represented by the demographics of Ukraine. I owe these scholars and practitioners deep gratitude for their contributions to this analysis.

Orthodox Christians

Philip LeMasters is an archpriest and pastor of a local congregation in the Eastern Orthodox Church and is a professor of Christian ethics and director of the honors program at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas. He became interested in global Christianity in his travels and has presented lectures in Scotland, India, Syria, Greece, Romania, the Netherlands, Canada and the Republic of Georgia. He says he works out six times a week, loves to cook for the family, and reads long, “dull” books on history and politics for fun. He is committed to building friendships across faith boundaries and often speaks at ecumenical and interreligious events.

LeMasters

Reflecting the beliefs of the 67.3% of Ukraine’s population that is Orthodox, LeMasters writes:

The liturgical and moral vision of the Orthodox Church … calls for greater emphasis on the challenges of making and sustaining peace than on those of making war. …. Commitment to a dynamic praxis of peace is fundamental to Orthodox Christian social ethics. … His All Holiness, the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, writes that “we have an ethical obligation to resist war as a political necessity and to promote peace as an existential necessity.” …. Orthodoxy does not have an explicit just war theory and sees the taking of life in war, even in a necessary and unavoidable war, as a tragic, broken undertaking for which repentance is required. … War is a manifestation of sin that reveals the corrupt spiritual state of fallen humanity. … If those in high places kept the commandments of the Lord, and we obeyed them in humility, there would be great peace and gladness on earth, whereas now the whole universe suffers because of the ambition for power and absence of submission among the proud. … The church may tolerate war as a tragic necessity for the defense of justice, the protection of the weak, and the preservation of the imperfect, yet still imperative, peace that is possible among the nations and people of the world.

Catholics

Father John Pawlikowski is a Servite priest and a founding faculty member at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, where he is professor emeritus of social ethics, having taught for 49 years. An active participant in Christian-Jewish dialogue, he served six years as president of the International Council of Christians and Jews. Pawlikowski was instrumental in the planning and development of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., on whose board he served by presidential appointment for four terms.

Pawlikowski

Concerning Catholicism in Ukraine, he writes:

There are two major branches of the Catholic Church in the Ukraine. The larger one is the Ukrainian Catholic Church, which is one of the largest so-called Eastern (or Greek) rite communities linked to the Vatican. … It has a strong presence in Ukraine, its spiritual home, with a concentration in the western (i.e., former Polish) part of the country. … The other part of the Catholic Church is the Latin rite Catholic Church, which has its own hierarchy as does the Ukrainian rite Catholic Church. … The Catholic community globally, despite many internal divisions, is clearly standing with Ukraine. The many, many statements (that have been issued) have called for negotiations but only if and when Russia halts its assault on Ukraine. The bishop head of the Ukrainian Catholic Church issued a statement condemning the Russian attack as a gross violation of human rights. In (the United States), Catholic masses in many parts of the country have called for an end to the war, with Russia clearly identified as the aggressor. Pope Francis paid an unprecedented visit to the Russian Embassy to the Holy See to protest to the ambassador regarding the humanitarian disaster occurring in Ukraine. And the next day, he personally phoned President Zelensky indicating his support (for) the people of Ukraine.

Protestants and non-denominational Christians

Elijah Brown is the general secretary of the Baptist World Alliance based in Falls Church, Va. The BWA is an organization begun in 1905 to unite global Baptists in ministry, prayer, fundraising for humanitarian and programmatic causes, education and fellowship. This loosely knit body that Brown directs has 51 million members representing 245 member bodies in 128 countries and territories of the world. He previously was executive vice president of 21Wilberforce, a Christian human rights organization based in Virginia, and was associate professor of religion at East Texas Baptist University in Marshall, Texas, where he was founding director of the Freedom Center. Brown has submitted reports to the United Nations and the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as numerous foundations and groups.

Elijah Brown

On a visit last week to Ukraine, Brown reached out to the global Baptist family, some of whom are part of the 9.9% of Protestant or non-denominational Christians in that country. He said:

I’m here in Kyiv, standing close to Sophia, the oldest church in all of Ukraine — a place where believers have been gathering to worship for almost 1,000 years. More than (150,000 Russian) troops are amassed on the three sides of Ukraine, and over the last several days that I’ve been here, there have been ongoing cyberattacks. Yet, over these few days, the national leadership of the Baptist Union of Ukraine have been gathering to pray and to plan. They’ve been planning for all their churches across this country to be centers of refuge in case there is widespread displacement. They’ve been encouraging every Baptist church to stock up on food and gasoline and other essential services so that, should there be chaos and confusion, the Baptist churches could be lighthouses in their community. As brothers and sisters within a global Baptist family, we are all called to be both peacemakers and people of prayer. As one Baptist family rooted in Jesus Christ as Lord, we bear witness to the biblical truth that “if one member suffers, all the members suffer.” It is vital for Baptists around the world to stand with those who are suffering and to fervently pray for peace. We remain grateful for both Russian and Ukrainian Baptists who are part of the Baptist World Alliance and are demonstrating faithful Gospel witness in their communities.

Jews

Rabbi Rachel Mikva is the Rabbi Herman Schaalman Chair in Jewish studies and the Interreligious Institute Senior Faculty Fellow at Chicago Theological Seminary. Prior to joining the CTS faculty, she was a congregational rabbi in Chicago and New York, where she advocated for justice and inspired her congregants to utilize the deep resources of their texts to help change the world. Professor Mikva participates in public discussions as broadly divergent as criminal justice reform, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, interreligious understanding and gender and racial justice. Cambridge University Press will publish her newest work, a textbook for undergraduates and graduate students on interreligious studies and engagement. Rabbi Mikva describes herself as “a rabbi and professor who works at the intersections of sacred texts, culture and ethics (who is) also an interfaith activist, a mother, an environmentalist, an empath, a pragmatist, and a perfectionist, (as well as a) feminist, an anti-racist, … and a lover of people.”

Mikva

Concerning the Judaism that 0.35% of Ukrainians practice, Mikva muses:

The Psalmist sang, “Seek shalom and pursue it” (34:15). Shalom, or peace, is not only freedom from violence but a wholeness for the flourishing of creation. Seeing this flourishing as central to God’s purposes, the rabbis of Late Antiquity taught: “Great is shalom! About all the other commandments in Torah it is written, ‘If you happen upon…,’ ‘If xyz happens…,’ (or) ‘If you see…’ — which implies that you must fulfill the commandment if the opportunity presents itself to you, but you are otherwise exempt. In the case of peace, however, it is written, ‘Seek peace and pursue it’ (34:15). ‘Seek it in the place where you are, and pursue after it in another place’ (Lev. Rab. 9:9).”

Muslims

Mohamed Elsanousi is a Muslim scholar and director of the Network for Religious and Traditional Peacemakers in Washington, D.C., “a network that strengthens peacemaking through collaboratively supporting the positive role of religious and traditional actors in peacebuilding processes.” This network has formed partnerships with more than 90 governmental, intergovernmental and civil society organizations around the globe. Prior to his leadership of this peacemaking network, Elsanousi was an assistant in the Office of Interfaith Relations of the Islamic Society of North America. His work led to establishment of a coalition of interfaith partners in combatting Islamophobia, the Shoulder to Shoulder Campaign. Elsanousi has coordinated a series of international convenings of the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, which have produced both the Marrakesh Declaration and the Charter for a New Alliance of Virtues — two landmark declarations that are Muslim-envisioned, -developed and -ratified. He was a featured speaker at the fourth National Baptist-Muslim Dialogue in 2018 at Greenlake Conference Center in Wisconsin. Elsanousi is trusted and respected by many major faith leaders in America, as well as by world faith leaders, senior government officials, and leaders of multilateral organizations. His knowledge of the Islamic world is without peer.

Elsanousi

Concerning the 0.05% of Ukrainians who are Muslim, Mohamed noted:

Peace is central to the Islamic faith. The very origins of Islam came from the word “peace.” Therefore, the promotion of peace is fundamental to the Islamic faith, from worship to transactional relations with God’s creation. The teachings of prophet Muhammad tell us that love is the basis of faith and “humans in their affection, mercy and compassion for each other are that of a body: when any limb aches, the whole body reacts with sleeplessness and fever.” In that spirit of humanity, we should feel the pain and suffering our brothers and sisters are going through right now in Ukraine and strive to bring peace.

Hindus

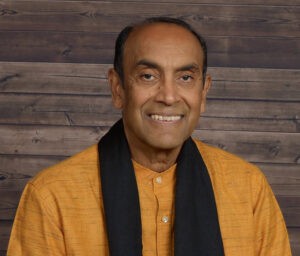

Anantanand Rambachan is professor of religion, philosophy and Asian studies at St. Olaf College, an elite Lutheran-sponsored school in Northfield, Minn. The author of numerous books, book chapters and articles, he has been engaged in interreligious relations for a quarter century as a Hindu dialogue partner and speaker. Rambachan was a Hindu guest participant at the last four World Council of Churches General Assemblies in Canada, Australia, Zimbabwe and Brazil. He is a regular member of the consultations of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue at the Vatican, as well as an adviser to Harvard’s Pluralism Project and a member of the International Advisory Council of the Tony Blair Faith Foundation.

Rambachan

Rambachan comments on the Hindu faith embraced by 0.1% of Ukrainians:

The hope for peace is a core aspiration and value in the Hindu tradition. Every Hindu prayer ends with a threefold recitation of the word “peace” (Om śantiḥ śantiḥ śantiḥ). The repetition of this word expresses the Hindu hope for peace in the natural world, in the human community and in our own hearts. At the same time, it emphasizes the interrelatedness of all three spheres. We will not attain peace in a world in which there is violence and injustice in human communities and in which nature is plundered and recklessly exploited. At the same time, we cannot be effective agents of peace in the world if we lack peace within ourselves. … The ethical value that most eloquently expresses this reverence for life is ahimsa (non-injury), regarded in the Hindu tradition as the foremost of virtues. In his understanding of the meaning of ahimsa, Gandhi explained that in its negative form it means abstention from injury to living beings. In its positive form, ahimsa is the practice of love and compassion (daya) for all. Ahimsa is the only enduring path to peace. … Sadly and so tragically, we are again witnessing the “soulless” unleashing of violence on the innocent people of Ukraine. Our hearts are shattered by every missile launched and with every precious human life lost.

Buddhists

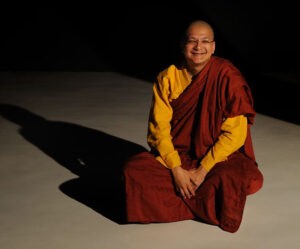

Bhikkhu Dhammadipa Sak is a Buddhist monk and the abbot of Amata Temple and the U.S. Zen Institute in Germantown, Md. He is vice president of the Buddhist Association of the United States and chair of the board of the Chinese Bhavana Association in Taiwan. He conducts meditation retreats throughout the United States and Asia. Sak is fluent in numerous languages both ancient and modern, including Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, French and English. His broad-ranging interests in Western philosophy, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and the interfaith movement, as well as his expertise in both early Mahāyāna and Theravāda Buddhism, make him a sought-after teacher.

Sak

About the 0.1% of Ukrainians who are Buddhist, Dhammadipa writes:

Beyond any doubt, the prime goal of the Buddha is to liberate from suffering (dukkhā nirodha). The Buddha once reminded us that a strong covetousness (kāma) serves as the cause, the source and the basis for “kings’ quarrel with kings, nobles with nobles, priests with priests, householders with householders, mother quarrels with son, son with mother, father with son, son with father… and they charge into battle massed in double array with arrows and spears flying and swords flashing; and there they are wounded by arrows and spears … whereby they incur death or deadly suffering.” In the history of human beings, over and over again, mankind has allowed such needless tragedies to occur, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which is an incontrovertible proof of the complete lack of human compassion and mutual respect, not to mention the Buddhist tenets of compassion, tolerance, reason and morality in engaging life.

Pagans

Andras Corban-Arthen is founder and spiritual director of the EarthSpirit Community based in Massachusetts. He also is president of the European Congress of Ethnic Religions, with headquarters in Vinius, Lithuania. He serves as a member of the advisory council of the Ecospirituality Foundaton, a United Nations Consultative NGO. Corban-Arthen has taught or lectured about pagan traditions throughout America and abroad since the 1970s, and he and his work have been featured in numerous books and news media. Originally from Galiza, Spain, he lives with his extended family in Glenwood, a 135-acre pagan sanctuary and nature preserve in the Berkshire Highlands of western Massachusetts.

Corban-Arthen

He introduces Ukranian paganism, an earth spirituality followed by about 0.1% of the population, in this way:

There are two main forms of Ukrainian paganism. The first represents the traditional, ethnic folk religion that can be traced back to the arrival of Christianity. It is mostly practiced among rural communities, though it is difficult to ascertain how much of it survives because for quite some time it was practiced side-by-side with Christianity. … The second form of paganism is known as Rodnovery and represents a modern revival of the Old Faith, which mostly involves people who for whatever reasons have rejected Christianity and are seeking to find the indigenous religion of their ancestors. In both forms of paganism there is a sense that the experience of divinity or sacrality is held by the land, by the natural world, and can be assimilated through the cultivation of a respectful and harmonious (i.e., peaceful) relationship with Nature. Much of the focus of Ukrainian paganism has to do with veneration of the old gods and goddesses, the ceremonial memorialization of the ancestors, the cultivation of “right relationship” with the land, and the maintenance of strong familial and community relationships. During the Soviet era, most forms of paganism were proscribed and even persecuted by the authorities. … With the fall of the Soviet bloc, paganism was able to resurface in Ukraine and has experienced considerable growth since. The current prospect of a Russian occupation and possible forced annexation is seen by many Ukrainian pagans as a threat to their survival.

Conclusion

Throughout my career as a minister, missionary, professor, scholar and writer, I have been enriched by my ecumenical and interfaith friendships. With the exception of LeMasters and Brown, whom I have known through my association with the wider Christian community, I have worked alongside all of the other contributors to this article when we were fellow members of the board of trustees of the Parliament of the World’s Religions. I will always be grateful for what I have learned from these many remarkable religious leaders and especially thankful for their kindnesses to me as their dialogue partner and friend.

From their testimonies and explanations, it is self-evident that the people of Ukraine — regardless of their religious affiliations or loyalties, their divergent personal histories or belief systems and their cultural habits or worldviews — all desire peace in their beloved country. They long for their families and communities to prosper. They want the very best of their spiritual teachings to shape the ways in which they can live together for the common good.

So, let us not only pray for those in Ukraine whose religion is like our own. Instead, may we remember the followers of all faiths — and the 11% who claimed no faith at all — who fervently desire that peace and human flourishing will soon replace these horrific days of war.

Robert Sellers

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is a past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren.

Related articles:

Baptists worldwide join in day of prayer for Ukraine

American churches turn to prayer and song in solidarity with Ukraine

Meditation on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine | Opinion by Ken Sehested

‘The situation here is terrible,’ Ukrainian Baptist leader tells European allies