The current struggle over Texas’ strict anti-abortion law perplexes many United Methodists who thought the issue of reproductive choice had been decided. Now they’re finding themselves back where clergy coalitions were in the 1960s and ’70s, seeking to support women in finding reproductive care even though the new state law effectively criminalizes such ministry.

In brief, Texas’ anti-abortion law, sometimes known as “the heartbeat bill,” outlaws abortion after about six weeks of pregnancy. That’s when a fetal heartbeat most often can be detected, but often before a woman experiences pregnancy symptoms. The law makes no provision for abortion in cases of rape or incest, including for minor girls.

Most importantly for United Methodist clergy, the law provides that anyone who “aids and abets” a woman to have an abortion through giving referral information or counseling can be sued by any citizen, a provision that has put clergy and other pastoral counselors at risk.

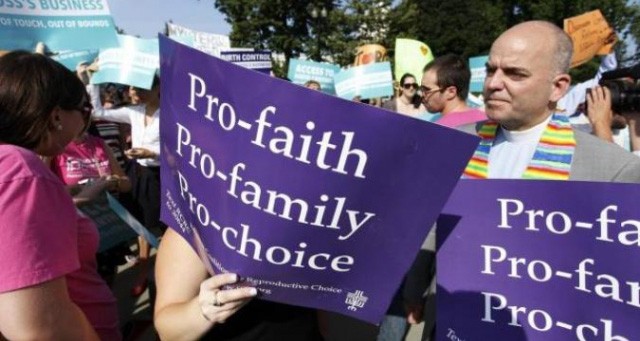

UMC women leading protests

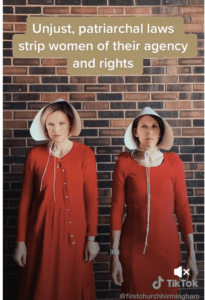

Two United Methodist clergywomen, Stephanie Arnold and Katie Gilbert, posted a protest of the Texas law on TikTok dressed in costumes resembling those in The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel of women’s slavery upon which a Hulu series was based. Arnold and Gilbert serve as pastors at First United Methodist Church of Birmingham, Ala.

Two United Methodist clergywomen, Stephanie Arnold and Katie Gilbert, posted a protest of the Texas law on TikTok dressed in costumes resembling those in The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel of women’s slavery upon which a Hulu series was based. Arnold and Gilbert serve as pastors at First United Methodist Church of Birmingham, Ala.

United Methodist Women also issued a statement denouncing the Texas law: “United Methodist Women, like The United Methodist Church, affirms that women and families need access to the full range of reproductive health care, with the guidance the church provides. … We pray that legislators in states across the country will make a different choice and allow women to discuss health care needs with their loved ones and health care providers.”

Lynn Parsons, a United Methodist laywoman in San Diego, urged her co-religionists to address the Texas law by becoming centers for reproductive health knowledge. In a commentary for UM News she wrote: “Why aren’t churches sources of information about birth control and prevention of venereal disease for their youngest, most vulnerable members who are having sex, even if we want to pretend they are not?”

Threat to pastoral ministry

Church historian William B. Lawrence noted the Texas abortion law’s threat to pastoral ministry in a recent commentary for UM News. Lawrence participated in a coalition, Clergy Consultation Service, that operated in the 1960s and ’70s to assist women with abortion access prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion nationwide.

William B. Lawrence

“If the newly passed anti-abortion law in Texas had been in place 50 years ago, my ministry could have ended soon after it started,” Lawrence wrote. “I could have faced civil court actions for which my $5,800 annual salary would have been inadequate to finance a legal response. I might have left the ministry because I could not afford to stay in it.”

He added: “What is more menacing about the Texas law is that pastors who provide counseling and referral services could be sued by persons who had no role in the pregnancy, the decision-making process or the ministry that a United Methodist is authorized to exercise by the Social Principles of the church. Anyone who happened to see a woman leave my church office with a pamphlet that might contain referral information about the health care to which she has a right, according to United Methodist policy, could file suit against me in civil court. … In effect, the law in Texas could make it financially impossible for a United Methodist to continue offering pastoral care to persons in need.”

UMC stance on abortion

In contrast to the Texas law, the official United Methodist stance on abortion, found in Paragraph 161 of the Social Principles, states: “We recognize tragic conflicts of life with life that may justify abortion, and in such cases we support the legal option of abortion under proper medical procedures by certified medical providers. We support parental, guardian, or other responsible adult notification and consent before abortions can be performed on girls who have not yet reached the age of legal adulthood. We cannot affirm abortion as an acceptable means of birth control, and we unconditionally reject it as a means of gender selection or eugenics.”

The United Methodist abortion stance represents decades of deliberations to create a nuanced guideline that is both thoughtful and reverent, said Robert Vaughn Jr., senior pastor of Community of Faith United Methodist Church in Herndon, Va. Vaughn is a director of the General Board of Church and Society, the social-justice arm of the UMC that is charged with carrying out its Social Principles, including those on reproductive choice.

“Terminating a pregnancy isn’t just a medical decision; it requires advanced pastoral care so that a person can look at the whole picture.”

“Terminating a pregnancy isn’t just a medical decision; it requires advanced pastoral care so that a person can look at the whole picture,” Vaughn said. “The United Methodist principle requires you to think through a decision, to seize the whole complexity of the question. It’s not as simple as some easy slogan.

“The church seeks to be sure that everyone has access to good reproductive health care, while also recognizing the disproportionate circumstances of those who have few choices because of lack of care, economic situation and other factors.”

Pastoral experience

Like Lawrence, Vaughn has direct experience counseling women about terminating a pregnancy. He said his experience has convinced him of the wisdom of the United Methodist approach.

“In one of my churches, I had a young woman who would term herself ‘pro-life,’” he said. “However, she was a young adult with a mental health condition that was managed with medication. The medication meant that she could function well, but it also meant that if she became pregnant, she couldn’t carry the pregnancy to term.”

Vaughn said the young woman did become pregnant and chose abortion, knowing the fetus wouldn’t be viable because of her own health condition.

“I remember walking with her as she and her family went through that situation,” he recalled. “She had to run the gantlet of people screaming at her before she reached a protected zone (that restricted demonstrations outside the clinic). It was good to be part of a denomination that respected her as an independent moral decision-maker, that gave her the right to choose.”

Vaughn was adamant that access to reproductive health care, including abortion, forms a key part of United Methodists’ “reluctant pro-choice” stance.

Vaughn was adamant that access to reproductive health care, including abortion, forms a key part of United Methodists’ “reluctant pro-choice” stance.

“To drive hundreds of miles for health care, including reproductive care, is just not appropriate,” he said. “In some places you have to go a long way for health care. Closing clinics and not providing training for full health care is a challenge. There’s a lack of health care in rural places. Some women don’t have the economic resources to travel, plus they’d need to take off work. It’s problematic that some states have put in delaying tactics such as requiring a first and a second appointment before a procedure.”

Ultimately, the United Methodist Church officially opposes the Texas abortion law in principle if not through open protest, according to its Social Principles: “Governmental laws and regulations do not provide all the guidance required by the informed Christian conscience. Therefore, a decision concerning abortion should be made only after thoughtful and prayerful consideration by the parties involved, with medical, family, pastoral and other appropriate counsel.”

Cynthia B. Astle is a veteran journalist who has covered the worldwide United Methodist Church at all levels for more than 30 years. She serves as editor of United Methodist Insight, an online journal she founded in 2011.

Related articles:

Talking about abortion is an opportunity to call on the grace of Jesus Christ | Opinion by Erin Jean Warde

SBC calls for ‘immediate abolition of abortion without exception or compromise’

When being ‘pro-life’ really isn’t: How I became a Democrat who opposes abortion | Analysis by Chris Conley