This June, the United States Supreme Court is expected to issue a ruling that could determine the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act. This 1978 law governs the adoption process for indigenous children, and its dismantling could have ruinous consequences for native tribes.

The exploitation of native children has always been the tip of the spear when it comes to dismantling the tribal sovereignty of Native Americans. After all, without children there can be no next generation to carry on religious and cultural traditions, preserve tribal languages and inherit tribal lands.

Sadly, churches along with Christian organizations and individuals have readily lent their support to these endeavors. Sometimes unwittingly, other times very much aware of the harm they were causing to native tribes.

‘Embedded theology’

“At the heart of it is some embedded theology, theology we operate on by default but rarely pull out and examine in detail, that has bought into the lie that indigenous peoples are more sinful than white people, and that their communities are more tainted by evil and “darkness” than other communities,” said Jodi Spargur, founder and director of Red Clover Initiatives. Red Clover helps churches understand their role in colonialism and promotes healing and justice through native-led action.

Jodi Spargur

“These pseduo-theological assumptions came out of the same writings that were used to justify the Crusades and the slave trade,” she added. “While we would reject wholesale the specific claims of these documents if we read them, we nevertheless operate under their influence.”

As far back as 1609, leaders at Jamestown received orders from Virginia Company lawyers in London to seize the children of the Powhatan Nation and educate them according to English customs and religion so that “their people will easily obey you and become in time civil and Christian.”

Because children are “moldable, in a formative state,” Spargur said, they were vulnerable targets for the “government’s assimilationist policies.”

The most well-known example is the kidnapping of the teenage Matoaka (Pocahontas), who was held hostage until she converted to Christianity. The crown and Company hoped hers would be the first of many conversions that would place native land into government hands under the pious guise of saving souls.

‘Christianizing’ native children

In 1879, Army officer Richard Pratt sought to institutionalize the assimilation of Native Americans, proposing the U.S. government forcibly remove native children from their families and send them to boarding schools where they would be educated about white culture, indoctrinated into Christianity and dispersed to work for white families.

“In Indian matters I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indians in our culture and when we get them under holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.”

Richard Henry Pratt

When native children arrived at his schools from the frontier, their long hair was cut short, they were given new “Christian” names and forced to speak only English. Their curriculum consisted of Bible stories and lessons on obedience. Addressing Baptist ministers at the 1883 Baptist World Convention, Richard Pratt remarked, “In Indian matters I am a Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indians in our culture and when we get them under holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.”

In a radical departure from the principle of separation of church and state, the U.S. government gave various Christian denominations, including Baptists, the task of running these boarding schools. Churches and their members seized on the opportunity to send missionaries and donations west. One Catholic mission promised supporters that “good Christians who came to the rescue would not only save those children, but reap their rewards with God.”

What native children needed rescuing from, however, was the schools themselves.

Underfunded schools

Corruption and the intentional underfunding by the government left children without enough food, clothing or bedding. When government assistance failed to meet the needs of the Levering Manual Labor School run by the Southern Baptist Convention, Annie Armstrong rallied the women at her church to sew clothing for the 240 students there.

408 federally funded schools operated between 1819 and 1969 across 37 states.

Residential schools also were rife with disease from unsanitary conditions and lack of medical care. Untold numbers of children died and were buried in unmarked graves behind the 408 federally funded schools that operated between 1819 and 1969 across 37 states. Native American children who survived endured physical, emotional, and often sexual abuse.

In 1958, the Bureau of Indian Affairs crafted a program even more extreme than boarding schools. The government’s Indian Adoption Project would not just remove native children from their lands and their cultures, it permanently removed indigenous children from their families and gave them to white families to raise.

“There were deliberate movements to take children, right out of hospital, and in some cases send them as far away as Germany feeling it was better for them to be raised in non-indigenous homes,” Spargur explained.

The Indian Adoption Project’s first director, Andrew Lyslo, rallied Christians to the cause to save “God’s forgotten children unloved and uncared for on the reservation.” Lyslo built relationships with churches and published articles in Catholic Charities Review, The Lutheran Witness and The Lutheran Standard to stimulate demand for native adoptions.

“The government had a policy to remove us and they used churches and other organizations,” said Sandy White Hawk, citizen of the Sicangu Lakota Nation and founder of the First Nations Repatriation Institute, an organization that provided research to the Supreme Court on native adoptions. Christian organizations heeded Lyslo’s call just as they had 100 years earlier in the boarding school era. Requests to adopt Native American children increased to such an extent that a “gray market” developed among social workers and adoption agencies to keep up with the demand.

“Social workers would come into a community or family and judge them by their white standards,” White Hawk said. Houses must “have so many bedrooms or had to have electricity, had to have running water, and people on the reservations didn’t have electricity during the 1950s.”

When she was 18 months old, White Hawk was taken from her parents and given to a non-native family. Had her parents resisted, “they would have been put in jail and I would still be taken,” she explained. “I want to think that people thought they were doing good by us, but what I don’t understand is why the solution was never ‘How do we help the family?’ instead of taking the child.”

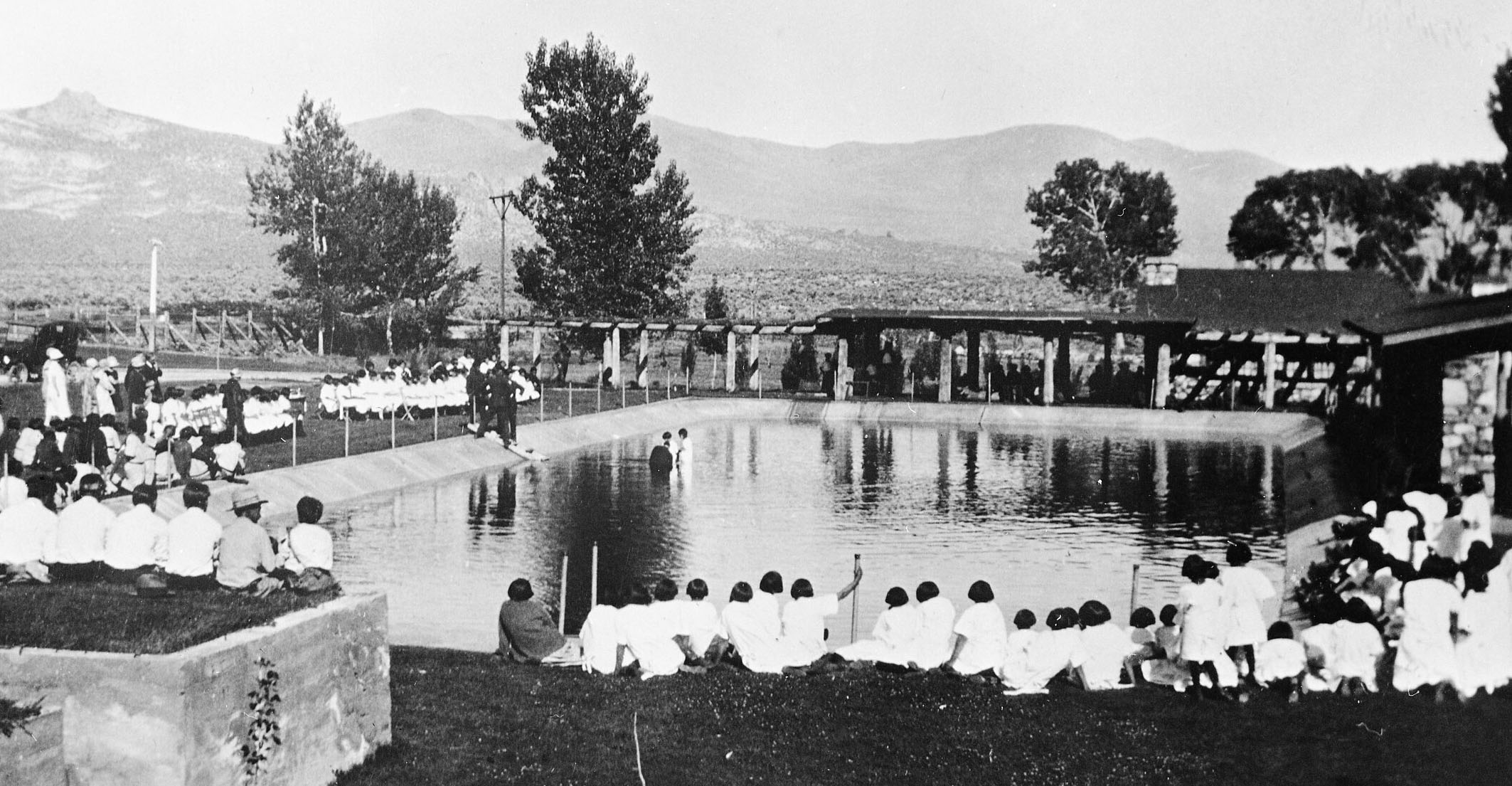

A student baptism at the Stewart School, 1930s.

Ignoring systemic injustice

Spargur thinks churches, like the social workers who stole Sandy White Hawk, are so focused on cultural differences they’re ignoring systemic injustice.

“Dominant culture churches in their good-hearted desire to care for orphan and widow, something Jesus told us to do, fail to look at what has created the fate of the orphan and widow and in so doing has failed to love their neighbor as themselves, having instead assumed that their neighbor is very different from themselves rather than looking for the ways that the systems that impact their neighbor are very different from the systems that impact them,” she said.

In states with significant indigenous populations one-third of native children had been removed from their tribal communities and placed in foster care or up for adoption.

In 1968, Native American women from the Fort Totten reservation in North Dakota pushed back against the injustices of the Indian Adoption Project. With help from members of the indigenous advocacy group the Association on American Indian Affairs, they journeyed to Washington, D.C., to raise awareness about the wholesale kidnapping of native children under the IAP.

After years of campaigning by tribes, grassroots activists, native social workers and the AAIA, Congress convened a series of hearings first in 1974, then again in 1977 to review the Indian Adoption Project and determine if legislation was necessary to protect the rights of native people.

Experts in the field of child welfare, child psychiatrists, tribal leaders and, most importantly, tribal members themselves testified before Congress. The Association on American Indian Affairs presented research showing in states with significant indigenous populations one-third of native children had been removed from their tribal communities and placed in foster care or up for adoption. Ninety percent of these placements were with non-native families. An examination of state records revealed that in Michigan one out of eight native children had been taken from their parents and put up for adoption, a rate 370% higher than non-native children.

Cheryl Spider DeCoteau

The most moving testimony in the hearings came from Cheryl Spider DeCoteau who, when she went to pick up her child from the babysitter, discovered he had been seized by a social worker and put into foster care without her consent and without any warning.

“He said I wasn’t a very good mother, and that my children were better off being in a white home where they were adopted out,” she recalled. “They could buy all this stuff I couldn’t give them and give them all the love I couldn’t give them.”

Indian Child Welfare Act

After four years of research, conferences, hearings and lobbying, and in consultation with native tribes and experts in the field, President Jimmy Carter signed the Indian Child Welfare Act into law on Nov. 8, 1978. When ICWA was introduced, Congress acknowledged the past discriminatory practices that had separated native children from their tribes and families and stated that these not only harmed children and parents but also “undercut the continued existence of tribes as self-governing communities.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act establishes guidelines for how tribes and states can work together to see native children through the foster care and adoption system safely and in a way that recognizes the unique political status and cultural significance of Native Americans.

ICWA’s first objective is to reunite children and parents and to give tribes and tribal courts the predominant role in reunification. When this isn’t possible, priority for adopting a native child is given first to extended family members, then to members of that child’s tribe and finally to other Native American families. Only after these avenues have been exhausted is the child eligible for adoption by non-native families.

ICWA has become the “gold standard”for adoptions. Research shows indigenous adoptees have a better life experience when placed with extended family members. As children, they were healthier and had fewer behavioral and mental health problems. By age 21, they were more likely to be employed or in school and less likely to need public assistance, be unhoused or be incarcerated.

“Even in loving families, native adoptees live without a sense of who they are.”

“Even in loving families, native adoptees live without a sense of who they are,” White Hawk said. “Love doesn’t provide identity. Because through adoption, we are living away from our homelands, away from our communities, away from our families. We don’t have a sense of who we are as an Indian person. We only have a sense of survival and making it work and trying to fit in.”

The court challenge

But Jennifer and Chad Brackeen want to see the Indian Child Welfare Act declared unconstitutional so white couples like themselves can adopt Native American children even when native adopters are available. The Brackeens already went to court to adopt their Navajo foster child and eventually received the tribe’s permission to do so. Now the couple wants to adopt the child’s half-sister even though a relative of the child, who is a tribal member, is willing to adopt her.

Jennifer and Chad Brackeen

This time the tribe is not relenting, and with lower courts unable to make a definitive ruling, the case has gone to the Supreme Court. The court heard oral arguments in Brackeen v. Haaland Nov. 9, 2022. Although the case centers on the adoption of one Native American child, the court’s decision could spell the end of tribal sovereignty for the 567 federally recognized tribes in the U.S.

The Brackeens believe their Christian faith compels them to foster or adopt children, a “sacrifice” Jennifer Brackeen compared in her blog to going on a mission trip and living without electricity. There she wrote, “It would not be an offering to God if it didn’t cost us something.”

For the last decade, evangelical churches and groups like Focus on the Family and Campus Crusade have promoted “orphan care” as a way to have a religion that is “pure and undefiled” as written in James 1:27. Joining them, the Southern Baptist Convention passed the Resolution on Orphan Care in 2009 calling for churches to preach and provide funding for adoptions, hold an annual adoption Sunday and “champion the evangelism of orphans.”

“Although well intentioned, these initiatives bear a striking resemblance to the Indian Adoption Project.”

Although well intentioned, these initiatives bear a striking resemblance to the Indian Adoption Project and other programs that have manipulated Christian charity for political and financial gain. According to Spargur, “Many indigenous in Canada would say foster care is the new residential school.

“Why do we continue to remove children from families and destabilize communities?” she asked. “Because it gives us land! We can say hey, there’s nobody there!”

A land grab?

While tribes have jurisdiction over a tiny 2% of land in the United States, that small percentage houses a third of the country’s coal, natural gas and oil reserves. The high-priced lawyers of Gibson Dunn, who earlier represented the Dakota Access Pipeline against indigenous people, eagerly volunteered to represent the Brackeens pro bono.

Lawyers linked to the casino industry whose bosses would like a share of the $30 billion earned by tribal casinos also assisted the Brackeen family. All told, ICWA has been challenged in court almost as many times as the Affordable Care Act. Both the fossil fuel and gaming industries would like to see ICWA toppled, because if the court decides tribes do not have sovereignty over their children, then they could also decide that tribes no longer have sovereignty over their land, sacred sites and natural resources.

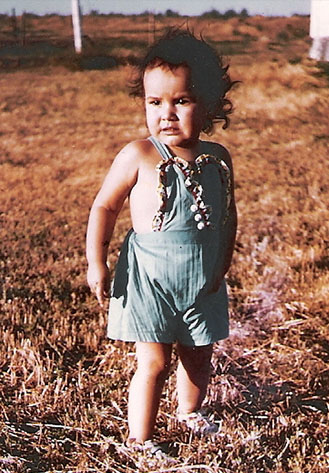

Sandy White Hawk as a child

The Brackeens and their lawyers claim ICWA is no longer needed in a “post-racial” America. However, lack of compliance and inadequate enforcement of the law means native children are still more likely to be removed from their families and placed in foster care.

Sandy White Hawk explained: “7.6% of children in need of placement are native children. We are less than 1% pf the population of the United States.”

For Spargur, this indicates systemic racism is still a factor and past legacies are continuing into the present. “In Alaska, 51% of children in foster care are indigenous. South Dakota it’s 50%.”

Race versus nationality

The argument before the Supreme Court centered on race versus nationality. The plaintiff’s lawyers argued ICWA was responsible for “reverse racism” because it privileges native adopters over non-native adopters and treats native children differently than other children in the adoption system. A similar rationale was used to argue against the 1964 Civil Rights Act and against affirmative action.

Those defending ICWA reminded the court that tribes are, and always have been, sovereign nations under the U.S. Constitution, so the issue is not one of race but of independent nations overseeing their citizens.

The discussion among the justices broke down along liberal and conservative lines with the notable exception of Justice Neil Gorsuch, who broke with the conservative justices and appeared to side with the native tribes and ICWA.

“Tribes are mentioned in the Constitution, we have the treaty power which … indicates that they’re separate sovereigns,” he said.

Justice Clarence Thomas, however, reduced native status to “some Indian blood,” an indirect reference to blood quantum, a pro-settler metric established by Congress as a way to determine who was Native American enough to receive tribal land.

Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson both emphasized Congress’ original belief in passing ICWA that “these children’s placement decisions (are) integral to the continued thriving of Indian communities,” as summarized by Justice Kagan.

Just what the Supreme Court will decide in Brackeen v. Haaland is difficult to predict. A total of 497 tribal nations, 62 native organizations, 23 states and the District of Columbia, 87 congresspeople and 27 child welfare and adoption organizations have signed on to 21 briefs submitted to the court in support of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

But will the majority of Christians agree with them, when in her blog Jennifer Brackeen claims “we knew this is what God wanted us to do,” referring to the adoption of a Native American child?

‘How is the Baptist church going to respond?’

In her work at the Red Clover Initiative, Spargur helps churches grapple with such questions by cultivating empathy with indigenous peoples. “We use a tool called the Kairos Blanket Exercise, which is an experiential workshop where participants become indigenous peoples, and we walk together through the history. When they understand something of the pain of having children removed, they start to realize the work we as churches have to do is about creating supports for whole families.”

Writing to Baptists in Canada, Spargur recounted a conversation she had with Chief Robert Joseph of Gwawaenuk Nation and ambassador for Reconciliation Canada who asked her: “How is the Baptist church going to respond? If the church doesn’t show up, I have no hope for this process of reconciliation. Because it is primarily a spiritual task.”

Spargur agrees and believes our call as Christians is first to those who are hurting.

“Our humanity is bound up with one another,” she said. “And that as people of faith we believe if any part of the body is hurting, we all hurt and we have too often chosen to only pay attention to the parts that aren’t hurting. And we are diminished because of it.

“Which is why I think it is important that we walk these really uncomfortable and really heavy parts of the journey, because that’s the only path I know of that leads us into true reconciliation.”

Related articles:

It’s past time to unearth and acknowledge our role in Native American boarding schools | Analysis by Laura Ellis

BJC luncheon highlights ongoing oppression of Native Americans