One-fifth of the United States population remains unvaccinated against COVID-19, and one-third are not fully vaccinated.

The gap between the vaccinated and unvaccinated remains for much the same reason that has been true from the beginning: Those least likely to be vaccinated are white, rural, evangelical Christians and Republicans.

This vaccine hesitancy is not based on institutional religious beliefs but more often on personal beliefs that inform religious interpretation. No major religious group and almost no Christian denominations oppose vaccination on theological grounds. According to Vanderbilt University’s Medical Center, the only religious denominations that do have institutional beliefs against vaccines are Dutch Reformed Congregations and faith healing denominations.

Public Religion Research Institute data show that eight of 10 members of every religious group believe the teachings of their religion do not prohibit vaccinations for childhood disease, and only 10% of Americans think the teachings of their religion prohibit vaccinations.

Those who refused vaccination are more likely to cite their religious beliefs than the teachings of their religions.

However, those who refuse to take the vaccine are much more likely to say that “getting vaccinated violates their personal religious beliefs (52%)” compared to the 33% who say that the teachings of their religion prohibit vaccination.

Further, the most vaccine-resistant group — Republicans who trust far-right news media — are twice as likely as other Republicans to say vaccines violate their personal religious beliefs (41% vs. 20%), and twice as likely as other Republicans in this subcategory to reference their religious beliefs rather than their religious teachings (41% vs. 22%).

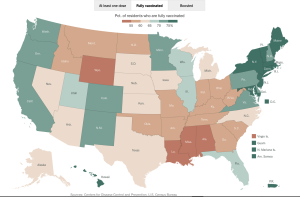

The New York Times recently ran an article discussing COVID cases by county, illustrated with a color-coded map of vaccination rates. The least-vaccinated areas fall in the Deep South and the middle of the country — the most reliably religious and Republican areas. The most-vaccinated areas show up along the East and West coasts, which tend to be less religious and more Democratic.

The New York Times recently ran an article discussing COVID cases by county, illustrated with a color-coded map of vaccination rates. The least-vaccinated areas fall in the Deep South and the middle of the country — the most reliably religious and Republican areas. The most-vaccinated areas show up along the East and West coasts, which tend to be less religious and more Democratic.

But why?

More than two years into the global pandemic, why are so many Americans still unmotivated to take the vaccine?

There is a weariness with the pandemic, which perhaps is why only 34.6% of Americans have received a COVID-19 booster vaccine. That’s half the number of Americans who have been at least partially vaccinated.

But claims of religious dissent also remain. PRRI data highlight the distinction between white evangelical Christians and others. Among Americans who continue to choose not to be vaccinated, faith reasons are more often cited than among those who are vaccinated.

Meanwhile, the rest of vaccinated America believes there are too many people seeking vaccine exemptions based on religious grounds. PRRI found 59% of Americans said too many people have used religion as an excuse to avoid the vaccine, and 60% of Americans believe “there are no valid religious reasons” to remain unvaccinated.

In the national campaign to increase vaccination rates, faith-based approaches and interventions have been shown to influence adults as well as parents of eligible children to become vaccinated — except for white Christian parents, who remain the least likely to say that faith approaches might positively influence their decision.

Real-life stories

In September 2021, The New York Times shared some personal stories from people explaining why they were hesitant to take the vaccine:

Sam Jones, pastor of Faith Baptist Church in Iowa, said he was willing to write a letter in support of congregation members’ religious exemption requests, stating, “A Christian has no responsibility to obey any government outside of the scope that has been designated by God.”

“A Christian has no responsibility to obey any government outside of the scope that has been designated by God.”

Crisann Holmes, a health care worker in Indiana who was seeking religious exemption, stated, “My freedom and my children’s freedom and children’s-children’s freedom are at stake” when her employer announced that her workplace would require vaccinations. In her exemption request, she wrote that the use of fetal cell lines from aborted fetuses to develop the vaccine contradicted her religious beliefs.

“Human life is sacred. The Bible tells you that your body is a temple,” she said. “The vaccine is made from aborted fetuses. The mandate is directly affecting my religious beliefs.”

Medical professionals have affirmed repeatedly that none of the COVID vaccines are “made from aborted fetuses.”

Yet Holmes cited a portion of 2 Corinthians 7:1 — “Let us purify ourselves from everything that contaminates body and spirit.”

In an October 2021 article by NPR, North Carolina pastor Jason McKnight stated that although he is vaccinated, he understands some congregants may have reservations. He says that as a pastor, “part of my role is to stand with the underdog. That’s what Jesus did,” and that the thought of people like nurses losing their jobs “because they’re just not ready to be vaccinated” seems harsh.

McKnight told NPR that “if a member asked for his signature on a religious exemption, he thinks he would sign it.”

Religious exemptions still sought

A year later, people are still requesting and being granted religious exemptions. A Bloomberg Law article from February 2022 discusses how hospitals cannot afford to lose any more employees over vaccine mandates, so they are accepting religious exemption requests to maintain the staffing numbers they need while avoiding legal scrutiny.

Hospitals cannot afford to lose any more employees over vaccine mandates, so they are accepting religious exemption requests to maintain the staffing numbers.

Institutional religious teachings can, of course, be cited by religious leaders, scholars or found within the official texts and doctrines of religions. However, claims made from personal religious beliefs are subjective to individual believers. Since they cannot necessarily be proved or disproved, it is difficult for companies to scrutinize these claims.

It is important to understand this distinction when considering the demographics of unvaccinated Americans and working to promote vaccines in religious communities. Vaccine-resistant and vaccine-hesitant Americans likely know that doctors, scientists and activists recommend getting a COVID-19 vaccine, and they do not claim that the official teachings of their religions prohibit or even discourage such vaccinations. These facts do not inform their decision to remain unvaccinated. Rather, it is their personal religious beliefs that keep them from getting vaccinated: They do not have faith in the vaccine.

Like Holmes does when she interprets 2 Corinthians 7:1, a verse that does not mention vaccines, believers often utilize religion to support their own previously held claims about vaccinations. Religion is not informing their decisions — personal thoughts are informing religious interpretations.

Warnings from history

History shows that such anti-vaccine attitudes can have dangerous consequences for communities.

A recent polio outbreak in Rockland County, N.Y., has hit Orthodox Jewish communities hard. An article from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency states that among Orthodox communities, childhood vaccine hesitancy is huge. Only 60% of children in Rockland County have received all three of their polio vaccines by the time they’re 2, compared to the national average of 92%.

As 8-year-old girl receives a polio vaccine, she watches a closed circuit television broadcast (showing Dr Jonas Salk as he inoculates a boy) of a training telecast for physicians and scientists, New York, New York, April 12, 1955. (Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

This means people in these Jewish communities, especially young children who are not yet vaccinated, are at a particularly high risk of being infected with polio.

This has happened in Orthodox Jewish communities before, such as in 2019 when “Vaccine Safety Handbook” magazines were passed out to community members. The magazine “disputes the well-established dangers of illnesses like measles and polio” and at the time served to discourage parents from getting their children vaccinated against measles.

Despite there being no official Jewish teachings against vaccination, these magazines promoted dissenting attitudes toward them, contributing to outbreaks of diseases like measles in 2019 and polio this year.

Official religious teachings seem generally to have no official stance on vaccination, although some religious leaders do encourage it, like Pope Francis, who stated that taking the vaccine is a “moral obligation” out of one’s love for others.

Despite this encouragement from the pope himself, many people of faith still believe the vaccine violates their personal beliefs. And because they conflate personal beliefs with religious ones, they find refuge in religious exemptions.

Related articles:

Faith leaders are key to reaching herd immunity in U.S., researchers say

Interpreting the data: Why are some Christians getting vaccinated and others aren’t? | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

A pediatrician’s advice to parents worried about the COVID vaccine and their children

Looking for a religious exemption to a COVID vaccine mandate? Most denominations won’t help you