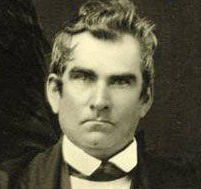

During his 1846 Illinois campaign for the U.S. Congress, Abraham Lincoln, candidate for the Whigs, soon to become the Republican Party, was charged by his Democrat opponent, the Methodist circuit rider Peter Cartwright, with being “an open scoffer of Christianity” and an unconverted “infidel” who identified with no church.

Lincoln responded with a handbill asserting his religious position, acknowledging: “That I am not a member of any Christian Church, is true, but I have never denied the truth of the Scriptures; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or of any denomination of Christians in particular.”

Peter Cartwright

He added: “I do not think I could myself, be brought to support a man for office, whom I knew to be an open enemy of, and scoffer at, religion. … (no) man has the right thus to insult the feelings, and injure the morals, of the community in which he may live.”

A frontier revivalist extraordinaire, Cartwright continued to challenge his opponent’s religious views, or lack thereof, prompting Lincoln to show up at one of the Methodist preacher’s revival meetings.

The service ended with the requisite altar call, after which Cartwright declared: “I observe that many responded to the first invitation to give their hearts to God and go to heaven. … The sole exception is Mr. Lincoln, who did not respond to either invitation. May I inquire of you, Mr. Lincoln, where you are going?”

“Brother Cartwright asks me directly where I am going. I desire to reply with equal directness: I am going to Congress.”

The answer was classically Lincolnesque: “I came here as a respectful listener. I did not know that I was to be singled out by Brother Cartwright. I believe in treating religious matters with due solemnity. … Brother Cartwright asks me directly where I am going. I desire to reply with equal directness: I am going to Congress.”

Abraham Lincoln won that election by a substantial majority vote. Reverend Cartwright did not claim it had been “stolen.”

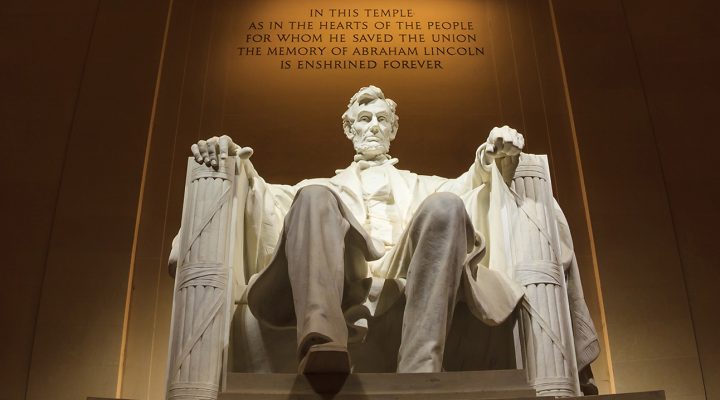

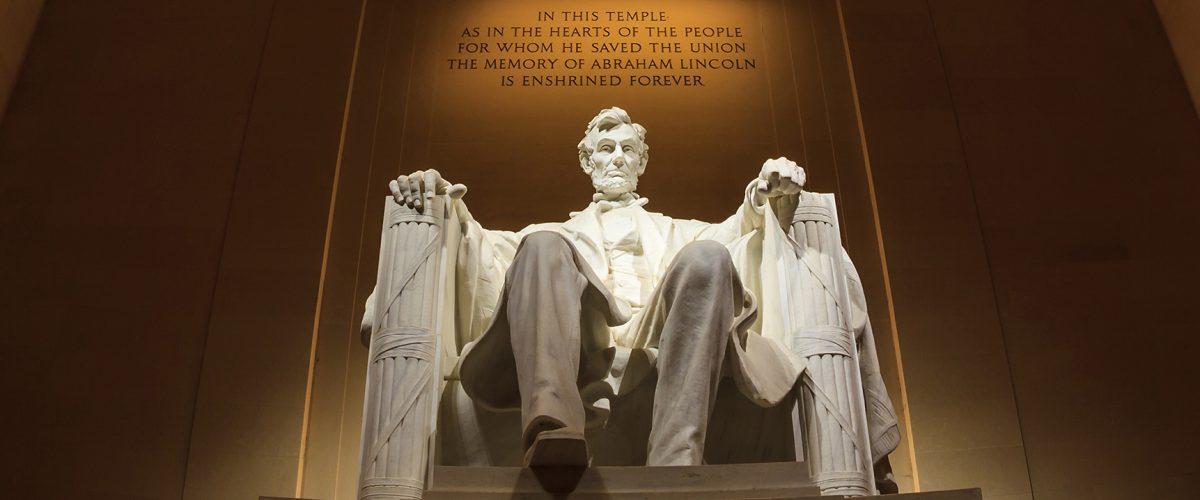

Now, 176 years later, in a political environment overshadowed by varying, even contradictory, religious assertions and an increasingly politicized churchly environment, we might ask: Was Abraham Lincoln a 19th century “none?” Although a frequent church attender and Bible reader, Lincoln never was baptized and never claimed a specific Christian profession.

In 21st century parlance, the term “none,” describes a burgeoning 30% of Americans whom sociologist Ryan Burge says “do not identify with any particular religion.” Some consider themselves atheists or agnostics, while most are simply without religious affiliation, perhaps “believers but not belongers,” or “spiritual but not religious,” descriptions that could well be applied to America’s 16th president.

“The religio-political context of Lincoln’s day suggests striking parallels with that of our own fractured times.”

The religio-political context of Lincoln’s day suggests striking parallels with that of our own fractured times. In a 1997 journal article, historian Richard Carwardine wrote that in mid-19th century America, “most male evangelical Protestants were deeply involved in politics. They attended rallies, read political papers and canvassed for particular candidates.”

“Party strategists” he said, sought to channel “religious passions” into political action. They “played ‘recognition’ politics by running candidates known to be attached to denominations whose members’ votes were pivotal; and they replicated the evangelicals’ mind-set of a world divided by irreconcilable forces.”

Democrats welcomed certain “religious outsiders,” particularly those marginalized Protestants (such as Baptists) who had encountered certain forms of political harassment by state-privileged Congregationalists in New England and Anglicans in Virginia. Whigs “made a bid for the support of evangelicals who, while committed to the classic Protestant virtues of self-control and self-discipline, also welcomed an interventionist government that would regulate social behavior and maintain moral standards in public life.”

Has nothing changed?

“Religious loyalties and antagonism were a major, and sometimes the main, determinate of party attachment.”

Carwardine concludes that “one of the important realities of Antebellum voting” was that “religious loyalties and antagonism were a major, and sometimes the main, determinate of party attachment. Interdenominational conflicts and differing views on the proper role of government in sustaining a Christian republic helped determine party affiliation.”

Does any of this sound familiar in 2022?

In Lincoln’s America, chattel slavery was the issue that split the nation and its churches racially, politically, regionally, theologically and biblically. By the 1830s, unsuccessful anti-slavery efforts turned many Northerners to abolitionist condemnation of slaveholding as a massive evil requiring immediate manumission. As abolitionism intensified, so did Southerners’ “biblical defense” of slavery, anchored in such as “Bondservants, obey in everything those who are your earthly masters,” found in Colossians 3:22.

Antebellum Virginia Presbyterian minister/theologian Robert L. Dabney urged Southern clergy to defeat abolitionist claims by asserting scriptural support for slavery as a political strategy, “to push the Bible argument continually, drive abolitionism to the wall, (and) compel it to assume an anti-Christian position. By so doing we compel the whole Christianity of the North to array itself on our side.”

In an expansive 1854 speech in Peoria, Ill., Abraham Lincoln attacked the Kansas-Nebraska Act that would have extended slavery by popular vote. No abolitionist, he nonetheless referenced his faith as formative in his hatred of slavery, noting, “If the Negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal;’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.”

He further declared: “I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world — enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites — causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty — criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.”

Lincoln’s words from 1854 seem hauntingly applicable to our 2022 national dilemma and tainted global “witness.”

- Our “republican example” is questioned across the world. Although slavery was abolished, racism remains.

- The “enemies of free institutions,” at home and abroad, “taunt us as hypocrites,” with some justification.

- “Our sincerity” as the land of the free is questioned by “the real friends of freedom.”

- The nation itself seems in “open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty” with each new day.

- Worse yet, American Christians in 2022 seem as divided as those who occupied North and South in what certain Americans now call the “Civil War I.”

As Christians in a divisive environment, are their cautions we might all observe whatever our ecclesial-political differences?

- Might we work together to avoid the “slavery hermeneutic,” a method of biblical interpretation that claims scriptural authority for practices that undermine the gospel?

- Might we acknowledge the theological and political struggles of our times, while resisting the rhetoric of warfare? To declare, “We are at a time of war” in a nation armed to the teeth is to offer potential cover to those inspired to violent political acts.

- Might we exercise caution in appropriating the policies of one political faction as the only option for Christians desiring “to vote the right way?”

- Might we resist dismissing the “nones” all too quickly as “open scoffers of Christianity,” or worse yet “infidels,” since our own behavior or rhetoric may have sent them packing? Rather, we might join Abe Lincoln in becoming “respectful listeners” of their concerns.

- Might we then go and vote our consciences, “as God gives us to see the right?”

Bill Leonard

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

What Abraham Lincoln has to say about our national grief this Presidents Day | Analysis by Harold Ivan Smith

Is it time for another Gettysburg Address? | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

Lincoln’s religious influence in forging Emancipation Proclamation still evident after 150 years

What Abe Lincoln tells us about Trump, Biden, guns, God and Falwell Jr. | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Abraham Lincoln, Susan B. Anthony and Adam Sandler: Signs of a church that is more than a museum | Opinion by Brett Younger