The insidious and chronic nature of church sexual abuse is an outgrowth of patriarchal concepts of the divine that provide theological cover for abusers and shame for their victims, said the authors of a new book on theologies of abuse.

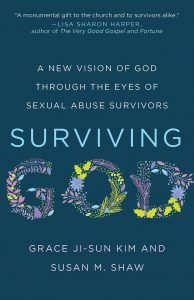

Language depicting God as “father,” “king,” “master,” coupled with an emphasis on the omnipotence and omniscience of God, is problematic because it emanates from patriarchy, said Susan M. Shaw, co-author of Surviving God, A New Vision of God Through the Eyes of Sexual Abuse Survivors.

“These are the characteristics we associate with men, and having a God like that essentially reinforces and justifies men having exclusive power over women, children, feminized men and marginalized other people,” Shaw said during a recent episode of “The State of Belief,” a podcast moderated by Interfaith Alliance President Paul Raushenbush.

“We really wanted to explore the ways those images, that language and those beliefs have created a framework that enables abuse in the church and then at the same time minimizes what happens to survivors because they’re merely women or they’re less important.”

Shaw is an ordained Baptist minister and professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She was joined on the March 23 episode by Surviving God co-author Grace Ji-Sun Kim, professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind. Both are columnists for Baptist News Global.

Shaw is an ordained Baptist minister and professor of women, gender and sexuality studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. She was joined on the March 23 episode by Surviving God co-author Grace Ji-Sun Kim, professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind. Both are columnists for Baptist News Global.

Shaw and Kim, both of whom identify as abuse survivors, discussed their new book’s exploration of the ways religion contributes to sexual abuse and what faith becomes for its survivors.

Patriarchal notions of God communicate the message that God has authority over men the way men have authority over women and children, Shaw said. “We thought that was important to explore because one of the big questions is, what kind of God are we suggesting there is when we say God is all powerful? Because that means God either caused, willed or allowed abuse, and that’s not really a God I would want much to do with, nor is it the God I’ve experienced.”

The book is also intended to let Christians know sexual abuse occurs in churches as much as it does in wider society, and that ignorance of that fact actually plays into the hands of predators, Kim said.

“There’s a weird dynamic that happens in the church because the church, the theology, the patriarchy and male images of God just allow this and sometimes make it seem like it’s OK that it’s happening,” she said. “We have let so many youth pastors … and other ministers and leaders get away with this.”

Raushenbush asked whether the Southern Baptist Convention and other religious groups embroiled in sex-abuse scandals are making any meaningful progress toward addressing the causes and conditions of abuse: “How have you been viewing, within the church, the reckoning with sexual abuse that has taken place?”

Kim said there has been no reckoning in recent times or throughout church history, for that matter. “The church doesn’t want to deal with it because it’s going to cost them a lot of money. So, finances also determine this issue and we just want to make ourselves look good.”

Failure or refusal to accept that abuse is possible in a congregation is another barrier to that reckoning, Kim added. “It happens in society, it happens in the workplace, it happens in the schools, but of course we’re Christians, so it can’t happen in our churches. We’re in a state of denial. We cannot imagine a pastor doing this, or a youth pastor, or a youth leader or an elder.”

“If we’re going to break this cycle of violence, the perpetrator needs to change, needs to do more because we cannot treat it as this ‘cheap grace’ that Dietrich Bonhoeffer talks about.”

When knowledge of abuse surfaces, many churches are quick to forgive in an effort to sweep the matter under the rug and move on, while survivors are left in isolation to deal with the physical, emotional and spiritual consequences of abuse, the authors reported.

“We tend to blame the victim and then the perpetrators are let go free. They’re forgiven and then we forget about it. But if we’re going to break this cycle of violence, the perpetrator needs to change, needs to do more because we cannot treat it as this ‘cheap grace’ that Dietrich Bonhoeffer talks about,” Shaw said. “It requires us to act and change and take responsibility for what has happened. If people don’t take responsibility, then it’s going to continue to happen from generation to generation.”

Adopting a “kaleidoscope view” of God can heal the church of the patriarchal theology that spawns sexual abuse and bring healing to survivors, Shaw asserted. “It suggests there’s not one way to see God, but that rather it’s ever changing and multifaceted. That keeps us from thinking we know it all, that we have all the right answers, and then from excluding the experiences of others.”

Raushenbush described Surviving God as a “church too moment” because it exposes the church’s complicity in sexual abuse. “It’s really important that you both really lean into the fact that abuse has happened in the church and it’s not some small thing or accidental thing or incidental thing, but it’s actually connected to broad questions of how church functions and how church is experienced by people, especially people who are in more vulnerable positions.”

Related articles:

Southern Baptist theology set me up for sexual abuse | Opinion by Susan Shaw

Decent men of faith and sexual abuse | Opinion by Martha Dixon Kearse

Why can’t churches get handling abuse right? | Opinion by Susan Shaw