I went to a Red Sox game a couple of weeks ago for the first time in more than a year. Fenway Park recently reopened its stadium to fans but was selling tickets to partial capacity at the time.

Before we were let into the park, there was an additional checkpoint. As we inched forward to the front of the line, a man from Fenway security stopped us and asked, “COVID?” We responded, “Uh, no.” Then he promptly waved us through.

Laura Ellis

There was something comical and somewhat tragic in his one-word interrogation. It wasn’t even a full sentence — or even the full name of the disease that’s plagued the world for the last year and half. He didn’t ask if we had the virus, were recently tested, recently exposed or showing symptoms. No. Just the one word “COVID” with a slight lilt in his voice to indicate a question.

We entered the park laughing at the absurdity of this added safety measure that was little more than a formality. How many fans were stumped by such an interrogation? Did anyone actually reach this checkpoint and say, “Darn. I’ve been discovered,” then turn and go home?

This one-word question was comical to me in part because it was such a contrast to the university where I recently graduated that required weekly testing and daily symptom reporting from students. In just a few short weeks, the world seemed drastically different — as if we finally shed this “new normal” we’ve all been talking about to welcome back an “old normal,” embracing a post-pandemic world that looks largely identical to a pre-pandemic world.

Overwhelmed by our ‘new normal’

As life gets back to “normal,” I’m grateful for vaccines and celebrate our renewed ability to go to baseball games, reunite with distanced loved ones and rediscover the beauty of what it means to have physical community and connections once again. However, I fear the cultural attempt to erase everything we endured and witnessed in this last year and a half.

“I fear the cultural attempt to erase everything we endured and witnessed in this last year and a half.”

Since COVID-19 reached the United States, many people started moving through life with a tense anxiety of contracting the virus. Safety precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19 dictated every aspect of our lives as we felt the daily stress of avoiding contact with the virus. This instilled in people an unnatural fear of being in close proximity with other fellow humans.

I noticed this when I recently attended a small wedding. Although I loved being reunited with folks I hadn’t seen since before the pandemic, I found myself a bit overwhelmed by the all the people, sounds and small talk I hadn’t experienced in more than a year. I know other guests had similar reactions and felt exceedingly tired after the event.

As we slowly reemerge from the confines of our homes to rediscover the joys of life and in-person relationships, we might have to re-learn what it means to be in community. But practicing our social skills should not be the only thing on our minds as we enter a post-pandemic world.

Wounds and scars

Most of us enter into this time with personal connections both to people who survived the virus and other people who did not. More than 600,000 people in the United States have died from COVID-19. The number grows when it’s multiplied by the number of people who mourned these losses often from afar without goodbyes or the ability to properly grieve. In a different way, this lack of closure also is found in businesses, churches and schools that had to close their doors in a time when there could be no in-person final sale, dinner or goodbye party.

The immense loss and inability to mourn is palpable, and we know that these remnants of anxiety and grief do not merely disappear once the world reopens its doors. Rather, as we enter into this new time of partial liberation, we carry with us these wounds that have not been given the luxury to properly heal. Some of them are still gaping open, while others are uncomfortably glazed with thick layers of scar tissue.

“As we enter into this new time of partial liberation, we carry with us these wounds that have not been given the luxury to properly heal.”

In this time, I am reminded of Jesus’ resurrected body, which still bore the scars of crucifixion. We can learn something from the fact that Jesus did not return in his pre-crucified body. His body could not be the same one he had before the event of crucifixion. Rather, it showed evidence of the ordeal because his scars could not be erased.

Even though the violence against Jesus ended, the markings of trauma did not disappear. And even though ballparks, bars and churches are reopening, that doesn’t mean the trauma experienced by many in the wake of this pandemic is magically healed.

Scars of injustice seen as birthmarks

The virus also exposed other injustices that always linger below the surface but were put on full display in the wake of the pandemic. For example, inequities in the health care system became more evident as some struggled to access care. The virus affected people experiencing homelessness at higher percentages. And although vaccine rollout differed by location, those in positions of privilege often were able to access doses sooner, while some underserved populations still remain unvaccinated.

The last year and half also exacerbated preexisting forms of racism. Incidents of anti-Asian violence climbed to an unprecedented frequency as people of Asian descent were harassed and assaulted. And while trapped in our homes, the world more readily noticed the epidemic of police brutality against Black Americans, taking the lives of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, and Dante Wright, to name a few.

These kinds of wounds of systemic injustice have existed for so long that they easily could be mistaken for a birthmark. Particularly now as we move out from behind the screen and back into society, it would be easy to forget and ignore the wounds we’ve felt and seen in exchange for happier horizons. It is good and right that we embrace the hope we feel in this time. However, as our cities begin to reopen, let’s not fail to remember society’s open wounds. Let’s ask: How can the church as the body of Christ in the world attend to these wounds?

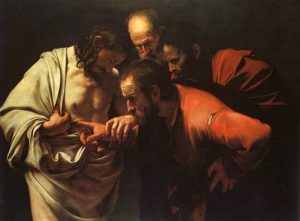

Jesus didn’t hide his scars

“The Incredulity of Saint Thomas,” Caravaggio, 1601–1602. Sanssouci Picture Gallery, Potsdam, Germany.

Although the desire to ignore the trauma of the last year and a half is a natural reaction, we should remember that Jesus did not conceal his scars. When Thomas asked to see them, Jesus offered his hands and pulled open his tunic. As signatures of an unclean death, his scars revealed the reality of crucifixion and testified that this event of violence could not be forgotten or erased. And just as Jesus’ body refused to let his followers forget the reality of crucifixion, neither should today’s followers forget the reality of the last year. As we emerge resurrected from these horrors, we must tend to the wounds and bear witness to the scarred body.

One of the most powerful examples of bearing witness from the last year can be found in the bravery of Darnella Frazier, the 17-year-old who recorded the longest video of George Floyd’s murder. When she saw Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck, Frazier escorted her 9-year-old cousin away, then returned to the sidewalk to record the nearly 10-minute video that millions of people watched. Nearly a year later, Frazier testified at Chauvin’s trial that she took the video because “the world needed to see what I was seeing.”

It would have been easier for Frazier to look away and leave with her cousin, but she stayed and recorded the event on her phone. Her decision to do so had a ripple effect in a larger movement because in that moment trauma was not silenced and a wound was not ignored. And in a way, her video became a scar, a signature of death, which testified that Floyd’s murder would not be forgotten.

“The reality is our post-pandemic world does not exist without wounds.”

I pray that the church has the same kind of tenacity to refuse to ignore trauma or cover up the painful aspects of the last year and a half. Because the reality is our post-pandemic world does not exist without wounds.

As we timidly come out of our homes with an air of reunion and celebration, let’s cling to the hope we feel. But may we also take time to lament the reality we have endured and witnessed. And may we not forget to tend to the wounds and scars, knowing that anxiety, loss, grief and insidious injustices are not cured by the vaccine.

We must aspire to Darnella Frazier’s audacity to reveal truth — because healing and reconciliation are possible only by exposing scars and acknowledging wounds.

Laura Ellis currently serves as a Clemons Fellow with BNG. She recently graduated from Boston University School of Theology with a master of divinity degree. She is originally from Abilene, Texas.