I was one of a handful of Baptist students at Duke Divinity School in the mid to late 1980s. Rocked in a Baptist cradle, baptized in a Baptist church and educated at a Baptist university (Wake Forest), I wanted to see how others thought about and taught religion in graduate school, so I chose Duke over some of the traditional Baptist seminaries.

What I discovered there is that while most of the differences between the Methodist and Baptist churches are around the margins, some are stark and instructive.

The importance of John Wesley to the UMC

I hadn’t been at Duke long when I realized how important John Wesley and his singular religious experience at Aldersgate is to Methodism, as it was recounted ad nauseam during my three years there. I even impishly imagined a new refrain of “Holy, Holy, Holy” for the UMC hymnal:” God in four persons, don’t forget Wes-ley.”

David Ramsey

John Wesley was one of 19 children born to Samuel and Susannah Wesley in England. John and his older brother Charles pursued similar academic and religious interests. On a mission trip to Georgia, both brothers voiced doubts about their faith. They returned to England believing their lives and ministry had failed. John Wesley wrote of his experience in Georgia, “I went to America to convert the Indians; but, oh, who shall convert me?”

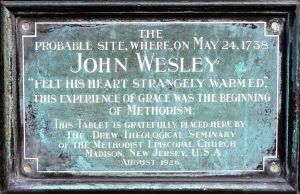

The answer to his question came shortly after his return from America. On May 24, 1738, in a Moravian meeting house on Aldersgate Street in London, Wesley wrote in his journal that now-famous account of his conversion:

In the evening I went very unwillingly to a society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther’s preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation; and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.

A plaque erected on Aldersgate Street in London commemorates this experience:

Think critically about this origin story and its impact on Methodism. Almost three centuries ago, one solitary man, perhaps dejected and depressed, felt something emotional or physiological, and an entire denomination would emerge from this singular experience. This is, for all intents and purposes, a mass conversion by proxy.

In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, Yuval Noah Harari argues that “most stories are held together by the weight of their roof rather than by the strength of their foundations … yet enormous global institutions have been built on top of that story, and their weight presses down with such overwhelming force that they keep the story in place.”

John Wesley

Wesley’s weight on the United Methodist Church is immense and immeasurable; however, it invites a simple question: What if John Wesley simply had indigestion or heartburn at Aldersgate? Maybe Wesley simply had a bad meal? After all, his Aldersgate experience was in the evening.

Medicine could furnish the context and explanation for Wesley’s experience. So could psychology. Abraham Maslow might describe an event like Wesley’s as a “peak experience.” For Maslow, a peak experience was a moment of awe, ecstasy or sudden insight into life as a powerful unity transcending space, time and the self.

Whether Wesley had indigestion or a peak experience or a spiritual awakening, his conversion story was about him. Even his lingering doubts were about him and his faith, or lack thereof. Conversion for some, or “getting saved” or “being born again” is the summum bonum of Christianity and is wholly inward.

And this is where Methodism intersects with other Christian denominations, including Baptists.

“Salvation for many Christians is simple and solipsistic: getting myself to heaven.”

Salvation for many Christians is simple and solipsistic: getting myself to heaven. Forget acts of kindness or mercy. Forget any crimes or atrocities. All that matters at the end of my life is whether or not I’ve chosen to believe what might be an ancient myth.

Billy Graham put a finer point on this notion. Returning home with a friend the night he was “saved,” Graham said, he thought: “Now I’ve gotten saved. Now whatever I do can’t un-save me. Even if I killed somebody, I can’t ever be unsaved now.”

Applying the logic of this notion, Hitler, as long as he prayed the sinner’s prayer at some point before death, would find himself in heaven the instant he killed himself, and the 6 million Jews he exterminated would be burning in hell due to their disbelief in a bygone story. Gassed by Hitler and then burned by God. Sounds like a Quentin Tarantino movie.

The late Harold Bloom, an American literary critic and Yale professor, observed and critiqued this phenomenon in The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation:

Freedom, in the context of the American religion, means being alone with God or with Jesus, the American God or the American Christ. In social reality, this translates as solitude, at least in the inmost sense. The soul stands apart, and something deeper than the soul, the Real Me or self or spark, thus is made free to be utterly alone with a God who is also quite separate and solitary.

E.Y. Mullins

Bloom was fascinated with the Southern Baptist notion of “soul competency,” a term he attributed to E.Y. Mullins, a Southern Baptist minister, educator and seminary president. Bloom quotes from Mullins’s Axioms of Religion (1908):

Observe then the idea of the competency of the soul in religion (which) excludes at once all human interference, such as episcopacy, and infant baptism, and every form of religion by proxy. Religion is a personal matter between the soul and God.

Bloom argued that each Southern Baptist is at last “alone in the garden with Jesus,” citing a hymn from my childhood. And, adds Bloom, “soul competency is remarkably like erotic competency, since there is no room for a third when the Baptist is alone with Jesus.”

In any case, there is in soul competency, says Bloom, “the requisite element of isolation and of intense individuation. It is a very rough version of Emersonian self-reliance.”

“While Methodists and Baptists might overlap on the notion of soul competency, it’s safe to say there is no John Wesley or Aldersgate in Baptist history.”

While Methodists and Baptists might overlap on the notion of soul competency, it’s safe to say there is no John Wesley or Aldersgate in Baptist history. Some might point to John Leland or Roger Williams; however, neither Leland nor Williams had a watershed moment as seminal and foundational to Baptist history as John Wesley’s Aldersgate experience is to Methodism.

But to think that an entire denomination was birthed and based on one man’s singular experience gives me pause and intellectual heartburn. It’s a case in point of Mullins’ “religion by proxy.” It also was one of several reasons I remained a Baptist while at Duke in spite of attempts by the dean of Duke Divinity School to recruit me to the United Methodist Church during my time there.

The Methodist Call System: The Yoke of Obedience

I got to know Dean Dennis Campbell quite well. In my first year, he sought me out and took a paradoxical interest in me. On the one hand, he had a vision for what eventually would become the Baptist House of Studies at Duke Divinity School, on whose board I later would serve. On the other, he tried recruiting me to become a Methodist minister.

He asked me to read his Yoke of Obedience: The Meaning of Ordination in Methodism. I already was struggling to keep up with the voluminous reading load in any given semester at Duke, and he wanted me to add another book to that list? I somehow found time to read his book, and when we met to discuss it, he asked me, “So, what did you think of my book?” As I recall, I simply said, “I’m not ready to be yoked.”

In the UMC, ministers are employed, or “yoked,” by a conference and bishop. As such, they are routinely moved from parish to parish during their careers. A typical first “charge,” as it’s called, might consist of two or three small churches in a rural setting.

Then a minister typically progresses through a series of increasingly larger churches. Taller steeples (larger congregations) are usually reserved for more seasoned (older) ministers. My UMC friends at Duke also informed me that the entire process was quite political. It wasn’t so much what you knew, they said, but who you knew, or who knew about you.

By contrast, a minister in a Baptist church is called or employed by that local congregation. The Baptist polity of the autonomy of the local church means Baptist churches aren’t beholden to any denominational hierarchy. The church that hired that minister can fire her or pressure her to leave.

“I wasn’t married at the time, but I wasn’t comfortable with the scenario of moving a family every four or five years.”

I wasn’t married at the time, but I wasn’t comfortable with the scenario of moving a family every four or five years. Ambitious, I also didn’t want to wait until I was older to serve a large congregation. I compared being a Baptist minister to being a free agent in professional sports. I wanted control over where I would work and how long I would stay there.

The process by which a Baptist church “calls” a minister is no less political than the UMC, however, and the role of the candidate in that process is far from passive. I struggled to find an open Baptist pulpit as I began my job search in my third year at Duke.

Choosing Duke Divinity School, back then, meant being disconnected from the powerful networking machine of some of the traditional Southern Baptist seminaries. It also meant there were certain churches that wouldn’t even consider me — having gone to Duke.

Ironically, it was Dean Campbell who informed me of a vacant Baptist pastorate outside Charlottesville, Va., where I eventually landed and served four years.

“I did find the language of ‘call’ more than a bit disingenuous.”

I was ambitious, and so were many other Baptist ministers I met over the years. I saw nothing wrong with that; however, I did find the language of “call” more than a bit disingenuous. So, when I left my first pastorate, I told my congregation this: “I’ve accepted an offer from a larger church, in a college town, where I’ll make more money. Perhaps God is a part of this ‘calling,’ but let me ask you a question: How often have you heard of God calling a Baptist minister to a smaller church making less money?”

After the service, an older member of that church approached and said, “David, I’m so glad you didn’t give us that B.S. about God calling you to that church.” Turns out I wasn’t alone in my jaded view of the “calling” process in a Baptist church. He obviously had seen this charade before. I simply refused to play that game with that congregation, opting for transparency and honesty over what I perceived to be the dissembled language of the “call.”

When I arrived in that second church, I discovered how many and which Baptist ministers wanted the job. I also learned of the serious political maneuvering of some candidates, obviously unsuccessful, to be considered for what some deemed a coveted pulpit.

Looking back, I think the “yoke of obedience” in the UMC is probably a much safer process comparatively for a minister. When conflict arises in a Methodist church, a district superintendent meets with both the congregation and minister and tries to resolve the issue. If attempts at resolution aren’t successful, the superintendent moves that minister to another church, and a new minister is called to the conflicted parish. The damage to both the minister and congregation is hopefully minimal and short-lived.

“Being a Baptist minister, though, is like walking on a tightrope with no denominational safety net below.”

Being a Baptist minister, though, is like walking on a tightrope with no denominational safety net below. The same church that hired you a few years ago can now fire you or pressure you to leave. The ministerial honeymoon can turn into a pastoral nightmare. Sometimes there is a safe landing if a minister can find another Baptist church. Some landings, however, are rough. And the taller the steeple, the harder the fall.

I was fortunate to serve two relatively healthy Baptist congregations in Virginia in my brief career. But I knew bright and gifted Baptist ministers who were either forced to leave or fired from their churches, a scarlet letter now emblazoned on their foreheads.

The reasons for the terminations varied, but it was rarely a majority that forced the minister out. Rather, a small but vocal minority would find fault with their pastor and apply enough pressure on both the minister and the larger congregation to effect his ouster.

For a Baptist minister, the autonomy of the local Baptist church works — until it doesn’t. Sometimes the squeaky wheel of the disgruntled gets the grease in a Baptist church, and the minister is eventually removed from the saddle, and, like Absalom, he is “left hanging between heaven and earth,” his Baptist mule having moved on in search of a new minister whom they will “call” to magically lead them to the promised land of numerical and financial growth.

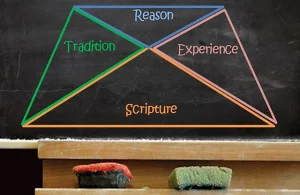

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral

Having examined the importance of John Wesley to the UMC and how ministers are “called” in that denomination, I now turn my attention to how Methodists think about matters of faith.

John Wesley believed four principle factors illuminate the core of the Christian faith for the believer: Scripture, tradition, experience and reason. This is commonly referred to in Methodist circles as the Wesleyan Quadrilateral.

- One Scripture can be clarified or challenged by other Scripture passages.

- A particular Scripture can be clarified or challenged by tradition, or what the larger church community says.

- Scripture can be clarified by reason.

- Scripture can be clarified by the Christian’s experience.

I found Wesley’s quadrilateral instructive as a Baptist minister. I suspected most thoughtful Christians, including Baptists, viewed the world through the same lens, albeit tacitly.

All texts require interpretation. No text interprets itself. Each of us brings our own implicit or unconscious biases and personal experiences to bear when reading any work of literature, including the Bible. And if a certain Scripture doesn’t pass the sniff test of reason, — such as the world being created in six literal days by God — you shouldn’t have to torture logic or sacrifice your intelligence to make sense of it.

All texts require interpretation. No text interprets itself. Each of us brings our own implicit or unconscious biases and personal experiences to bear when reading any work of literature, including the Bible. And if a certain Scripture doesn’t pass the sniff test of reason, — such as the world being created in six literal days by God — you shouldn’t have to torture logic or sacrifice your intelligence to make sense of it.

For me, however, over time, reason and experience began eclipsing Scripture and tradition. Epistemology collided violently with theology. Doubts shadowed belief. Wesley’s quadrilateral became a religious totem pole, with Scripture at the bottom, not at the top.

It’s one thing for this to happen to parishioners sitting in pews. When faith wanes for a minister, whose livelihood is at stake, it’s like a baseball pitcher losing his fastball, a pilot losing his vision, an opera singer losing his voice.

In In the Beauty of the Lilies, John Updike captures what happens when Scripture collides with reason and experience in the character of Clarence Wilmot, a Presbyterian minister. Confessing to his wife, Wilmot says:

My faith, my dear, seems to have fled. I not only no longer believe with an ideal fervor, I consciously disbelieve. My very voice rebelled, today, against my attempting to put some sort of good face on a doctrine that I intellectually detest. Ingersoll, Hume, Darwin, Renan, Nietzsche — it all rings true, when you’ve read enough to have it sink in; they have not just reason on their side but simple humanity and decency as well. Jehovah and His pet Israelites, that bloody tit-for-tat Atonement, the whole business of condemning poor fallible men and women to eternal Hell for a few mistakes in their little lifetimes, the notion in any case that our spirits can survive without eyes or brains or nerves … it’s been a fearful struggle, I’ve twisted my mind in loops to hold on to some sense in which these things are true enough to preach, but I’ve got to let go or go crazy.

Updike was narrating my story. Scripture and tradition no longer were intellectually tenable for me. Prayer seemed superfluous for an omniscient God. The notion of an omnipotent God didn’t square with a simple reading of any daily newspaper. And a God who needed sticky notes (blood) to mark the homes of Jews whose homes he would “pass over” on his way to kill Egyptian babies is malevolent, not omnibenevolent.

Little did I know that as I was losing my faith as a Baptist minister, I was not crazy and I was not alone. I was in good company. The Clergy Project was launched in March 2011 to create a safe and secure online community of forums composed entirely of religious leaders who no longer hold to supernatural beliefs.

I’ve come a long way from those days at Duke Divinity School. I left the ministry 26 years ago and started my life over from scratch at the age of 35. I’m now an executive in a company that didn’t even exist when I entered Duke.

Rudolph Bultmann’s Theology of the New Testament and Paul Tillich’s three-volume Systematic Theology are bookends in what’s left of my religious library. Sam Harris , Richard Dawkins and the late Christopher Hitchens make more sense to me now than the Bible ever did. And perhaps most important, as an immature 24 year old, I thought I knew a lot about God. Turns out, to quote Ruth Langmore from Ozark, I didn’t know s*** about f***. And I still don’t.

David Ramsey was a Baptist minister for 10 years. He holds degrees from Wake Forest University, Duke University, and he was a Fellow in Religion and Leadership Development at Princeton Theological Seminary. Ramsey is currently a principal with the world’s largest cloud technology company, AWS, and a published author. His author’s website is dbramsey.com

Related articles:

Methodists still follow John Wesley’s rules — mostly | Analysis by Cynthia Astle

United Methodists renewing their vows through annual Wesley Covenant Service may struggle this year