The race to find a safe and effective vaccine against the novel coronavirus is heating up, as society longs to get back to some sense of normalcy. But finding a vaccine is only one step on the journey that also includes ethical questions about who gets the first doses and who will be willing or not willing to receive the vaccine — and what responsibility we have for each other in our choices.

Many Americans say they’re unsure whether they will take a vaccine once it becomes available. In mid-May, only about 50% of Americans said they would get a coronavirus vaccine when one is available. A more recent Yahoo News poll has that number down to 44%.

Francis Collins

Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, laments that the virus and its vaccine have become politicized and suggests that the politicization is further driving a wedge between science and faith. Collins finds that his identity as both a scientist and a Christian create interesting conversations about things like the “neuroscientific basis of a spiritual existence.”

Faith and science

While much of the debate has been framed around trusting God or trusting science, Collins’ logic suggests we might consider how viral sciences engage our created bodies.

Both the scientific community and the faith community agree, albeit perhaps with different terminology, that the human immune system is nothing short of miraculous. For example, the way vaccines work is not by fighting off the virus. Instead, they stimulate immune responses in the body, helping the body more quickly and effectively ward off viruses.

Aside from whether or not a majority of Americans are willing to take a coronavirus vaccine, the United States faces an additional challenge of determining who gets priority access. There will not be enough doses to quickly give the entire population, and most vaccines likely will require administration of two doses. Since the government already is purchasing millions of doses of vaccine candidates before one has proved effective, priority has become a pressing question.

Should the government prioritize specific geographic regions that are hot spots? Certainly, frontline health care workers should have priority, but what about test subjects who received the placebo? What about other essential workers? Should we prioritize older Americans who are more at risk of death? Children who need to return to school? What about Black Americans and other people of color who have been disproportionately affected by the virus?

The Food and Drug Administration already has said that for a COVID-19 vaccine to receive approval, it would have be to at least 50% effective in stopping the virus. Certainly, the higher this percentage is, the better. Reducing the rate of infection by one-half may not seem like a lot, but the Centers for Disease Control reports that the typical flu vaccine each year can be anywhere from 40% to 60% effective. Cutting the rate of infection in half could go a long way in reducing the spread of the virus.

What’s happening now

Currently, more than 150 potential vaccines are in development, the majority of which have not reached human trials. Both the Guardian and the New York Times are tracking the progress of the most promising candidates.

Thanks to Chinese scientists who sequenced the genome of the COVID-19 virus in the beginning of the year, numerous vaccine candidates were able to begin testing quickly. After analyzing whether potential vaccines are both safe and generate an immune response in non-human subjects, human testing progresses in three phases. Phase I tests a small cohort of human subjects for safety and efficacy. Phase II tests a larger cohort, taking into consideration dosages and the demographics of human subjects. The final Phase III tests thousands of subjects and includes a control group given a placebo. Currently, numerous vaccines are in Phase III testing.

Not all scientists are approaching vaccine development against this novel coronavirus the same way, either. Some vaccine candidates utilize a weakened or inactive form of the virus to stimulate an immune response. Others target the unique spike protein on the coronavirus. Moderna, a U.S.-based company, is trying to create a vaccine that uses messenger RNA, a single strand of genetic material the cell uses to replicate the virus’ genetic code. No approved vaccine ever has used this type of approach.

Vaccines not a new debate

Debates over vaccines or viral inoculations have been a tradition in American religion since the Colonial period. Historically, there are good reasons to welcome the scientific innovation of vaccines as well as good reasons to be hesitant.

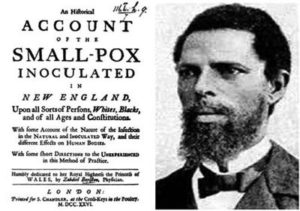

Scholars believe the smallpox virus, now a relic of the past, emerged more than 10,000 years ago in Northeast Africa. Some archeologists believe Ramases V of Egypt may have had the virus because of lesions found on his face. The virus ravaged indigenous populations in the Americas, and many colonists similarly succumbed to what became known as the “red death” or the “speckled monster.” By the 18th century, however, American colonists began a campaign of inoculation led by the Puritan minister Cotton Mather.

Mather, however, did not come up with the method of inoculation, according to an article in the journal Quality and Safety in Health Care. A servant of Mather’s by the name of Onesimus told him he had undergone an operation that gave him “something of the smallpox” and would “forever preserve him from it.” Onesimus explained to Mather how he had been inoculated using an African practice where a small amount of smallpox pus had been inserted into a cut in his arm. Similar practices had been used in China and India dating back centuries earlier.

Mather, however, did not come up with the method of inoculation, according to an article in the journal Quality and Safety in Health Care. A servant of Mather’s by the name of Onesimus told him he had undergone an operation that gave him “something of the smallpox” and would “forever preserve him from it.” Onesimus explained to Mather how he had been inoculated using an African practice where a small amount of smallpox pus had been inserted into a cut in his arm. Similar practices had been used in China and India dating back centuries earlier.

When the HMS Seahorse docked in Boston in April 1721 bearing crew members with smallpox symptoms, Mather began a campaign to get as many people as possible inoculated. Working with Zabdiel Boylston, Mather helped get 287 Bostonians inoculated, of which only 2% (six individuals) died.

Such a mortality rate was far better than the 15% of individuals who succumbed to smallpox from natural infection, translating to 842 deaths out of nearly 5,000 individuals. Boylston’s and Mather’s documentation of the vaccine’s effectiveness marks one of the first uses of numbers to evaluate a clinical trial.

Cotton Mather

Not all Bostonians appreciated Mather’s advocacy for inoculation, however. Opponents formed the Society of Physicians Anti-Inoculators who regularly offered public denouncements of inoculation. In November 1721, one critic hurled a bomb through the window of Mather’s home. While the fuse burned out before detonation, Mather was able to read the affixed note: “Cotton Mather, you dog, dam you! I’l inoculate you with this; with a pox to you.”

Despite this resistance, smallpox inoculation and later vaccination became a more common practice. The disease took the lives of roughly three out of every 10 people it infected, sometimes leaving survivors with mild to severe scars. By 1980, thanks to successful vaccination campaigns around the world, the 33rd World Health Assembly declared the world to be free of the disease.

And then there’s Tuskegee

Doctor drawing blood from a patient as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. (National Archives)

There is reason to be skeptical of vaccine trials though, particularly within communities of color. Beginning in the 1930s, doctors from the U.S. Public Health Service began studying untreated syphilis in Black men, in what is known today as the Tuskegee Experiment. The men were told they were being treated for bad blood and that they would receive free medical care.

The doctors, wanting to track the disease’s full progress, withheld the recommended treatment of penicillin from their subjects. Numerous men in the study died, went blind or experienced other severe health complications as a result of not receiving treatment.

After news of the unethical study was leaked and Congress held hearings, participants and descendants of the deceased received an out-of-court settlement totaling $10 million. Tuskegee is representative of numerous other studies from the 19th to mid-20th century that used people of color as test subjects.

What should Christians think about vaccines?

Any discussion of vaccines offers opportunities for Christians to consider who are the most vulnerable in our midst. While there are clear ethical and unethical boundaries to testing, there is no “correct” approach to priority access once a vaccine is available.

Bill Foege, who helped devise a strategy to eradicate smallpox, has said setting vaccination priorities requires “creative, moral common sense.”

In the meantime, skepticism regarding the development of a safe and effective vaccine is healthy. There is reason to believe scientists may not find an effective vaccine anytime this year, and we may have to rely on finding effective treatments for those who have been diagnosed with COVID-19.

At the same time, it’s important to keep in mind the goal posts — 50% efficacy and a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, Phase III study. By the time a vaccine is approved, thousands of individual test subjects will have proved its safety.

Medical science is a process, and the scientific community is currently working through that process as fast as it can. Because this process is taking place in such a public way, we have an opportunity to watch and learn.

Perhaps by treating this process as educational, Christians can better work to break down the division between faith and science.

Andrew Gardner holds a Ph.D. in American religious history and is the author of Reimagining Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists (2015).