This month, 160 years ago, Abraham Lincoln was ensconced in grief. The Civil War frustrated and hounded him 24 hours a day. Too many young boy-soldiers were dying; too many mothers and fathers were grieving. Gen. George McClellan was not only reluctant to fight, but derided Lincoln as “a coward,” “an idiot,” and “the original gorilla.” The daily demands for “more troops, more supplies, more money” challenged Lincoln’s energies and sanity.

Mary Todd Lincoln

And then there was Mrs. Lincoln — Mary, wife of almost 20 years and the mother of his four sons. Although born into the aristocratic Todd family in Kentucky, Mary was derided as a “woman of the prairies,” uncultured, coarse and worse, some whispered, a secret Southern sympathizer; after all, three of her stepbrothers were serving in the Confederate army and her brother-in-law, Benjamin Helm, was a Southern general.

Mary vowed to prove to the Washington elites — and gossips — that she had class and deserved respect as “Mrs. President,” her choice of title. She spent extravagant amounts of money on fashionable clothes. Mrs. Lincoln’s gleeful shopping sprees in New York City stimulated vivid criticism and outrage. Was she unaware that on winter nights, too many Union soldiers shivered without blankets, some without boots, most hungry?

Mary Lincoln had assessed the interior of the White House as an “old worn-out hotel.” She dreamed of a palace awed by Europeans and cherished by Washingtonians. Quickly, she spent the $20,000 Congressional appropriation for redecorating. The president agonized over her spending on items he dismissed as “flub-a-dubs,” such as china and imported French wallpaper. He had little idea how much money she was spending until he wrote checks to cover her overdrafts.

Lincoln well-acquainted with grief

Lincoln had not been immune from grief. The first Union general officer killed in the war, on Oct. 21, 1861, was Col. Edward Baker, a senator who had long been Lincoln’s friend and political ally. In fact, the Lincolns had named their second son Edward Baker Lincoln. Eddie, age 4, died during an epidemic in 1850 in Springfield.

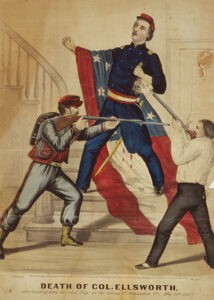

“Death of Col. Ellsworth,”

Lithograph, hand-colored, c1861,

Currier & Ives.

Also weighing on Lincoln’s soul was the death of Col. Elmer Ellsworth on May 24, 1861. Ellsworth had studied law with Lincoln in Springfield and had accompanied the family to Washington. He was like a young brother or son to the Lincolns and a beloved “older brother” to Lincoln’s two youngest sons.

Across the Potomac River lay Virginia and the Confederacy — the rebels! Early in the war, the District of Columbia was poorly defended and fortified. Given that day’s typography, Lincoln could look out a second floor White House window and see a Confederate flag waving in the distance. Some questioned how long before the Confederates invaded and raised their flag in Washington.

Knowing how that flag tortured the president, one night young Ellsworth organized a raiding party to cross the Potomac and capture “that flag.” Once on shore in Alexandria, they spotted the flag flying over Marshall House, a boarding house. Ellsworth and his men entered the house and quickly made their way up the stairs to the roof. They gleefully ripped down the flag. However, descending the stairs, the raiders encountered an irate innkeeper — with Southern loyalties — who shot Captain Ellsworth in the chest. The blast knocked Ellsworth backward onto the stairs dead. Ellsworth’s men returned fire and killed the innkeeper.

The soldiers picked up Ellsworth’s corpse and “that flag” and fled to the dock. They crossed the Potomac in silence. Ellsworth was “laid out” at the Navy Yard. After the shaken Abraham and Mary arrived, the president ordered the body taken to the White House to lie in state in the East Room. The emotional and spiritual wallop of that death wrecked the president’s composure. To a group of visitors he acknowledged his tears, explaining, “The poor fellow’s’ death … quite unmanned me.”

Thus, both Lincolns concluded the war would be bloody and personal and that no family would go untouched.

Mary focused on elevating her ‘star’

After spending incredible money — through legal appropriation and illegal schemes — by late January 1862, the first floor rooms of the White House finally met Mrs. Lincoln’s standard for grandeur. But what good, she mused, was that achievement without providing an opportunity to show it off and collect enthusiastic “oohs” and “ahhs” for her “refined” taste.” So, she announced a “soiree” but restricted invitations to only 500 individuals she judged the “crème” of Washington society. Some elites declined; others publicly demanded, “Did not ‘that woman’ know there was a war going on?”

The Lincoln White House china and crystal.

Her plans translated into an evening that historian Ronald White called “a model of fine elegance.” After dancing and mingling, the highlight was to be a grand midnight dinner catered by New York’s celebrated Maillards. The sumptuous midnight feast included pate de foie gras, oysters, duck, ham, venison, turkey, partridge, quail, beef, charlotte russe, bon bons, fancy cakes and “gallons” of champagne. The food and wine would be the finest; large confectionary models of a Union warship and Fort Pickens would decorate serving tables.

Life interrupts

Then life, as it does for all humans from time to time, upended Mrs. President’s plans. The White House water supply was pumped from the Potomac River. Given that raw sewage from the city’s thousands of latrines emptied into the river, the public health threat was enormous. As Mary fussed over details, Willie, 11, and Tad, 8, came down with typhoid fever.

Not to worry, physicians informed the First Parents. Their boys were young and healthy, and water-borne illness was “common.” In a few days they would be back to being the rascals they were known to be. Given that the planning was finished, Mary spent long hours tending her boys. At some point, the president decided to eliminate dancing at “her” soiree.

The night of Feb. 5, as the boys lay sick upstairs, the president and Mary greeted guests in a receiving line. And those guests did “ooh” and “ahh;” many offered effusive verbal bouquets to Mrs. President. Still, frequently during the evening and early morning (the event lasted until 3 a.m.), the Lincolns slipped out of the East Room and climbed the steps to the second floor to look in on their sons.

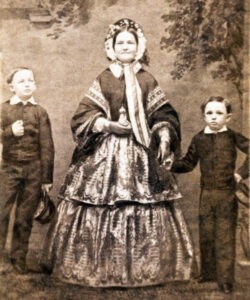

Mary Lincoln with Willie Lincoln (left) and Tad Lincoln (right).

After the gala, Willie’s condition deteriorated; the city was kept informed by updates published in newspapers. Soon letters arrived at the White House accusing the Lincolns of demonstrating disregard for the sacrifices of Union soldiers. For spending so extravagantly and sponsoring such frivolity in wartime, some charged that God had stricken the boys to punish the Lincolns. Those letters inflicted long-lasting psychological wounds that Mary could not refute.

On the afternoon of Feb. 20, just two weeks after the grand gala, William Wallace “Willie” Lincoln died. Mary became hysterical (as she again would when her husband was shot) and took to her bed for weeks. Lincoln groaned, “My poor boy. He was too good for this earth. … But we loved him so.” Lincoln informed John Nicolay, his secretary, “Well, Nicolay, my boy is gone — actually gone!” then burst into tears.

In 1862, the layout of the White House was different than today’s configuration. The president’s residence and office were narrowly separated by a partition. From morning until night, citizens lined up the grand staircase hoping to get a word with Lincoln or a job offer or a contract out of Lincoln. Even though Mary’s shrieking, wailing, sobbing could be heard throughout the White House, individuals clamored to get in to see President Lincoln.

Willie, meanwhile, was embalmed in the Green Room and lay in repose there; Mary would never again enter that room. On Feb. 24, Willie’s body was moved to the East Room. Lincoln had arranged for Phineas Gurley, pastor of New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, to conduct the funeral.

Willie Lincoln

“It is well for us,” Gurley began, “and very comforting on such an occasion as this, to get a clear and scriptural view of the providence of God.” (Similar words were spoken at funerals over fallen sons in both armies throughout the war.) Gurley concluded his homily with an injunction: “Acknowledge his hand and his voice, and inquire after his will.” The pastor stopped just one short step of concluding that Willie’s death had been “God’s sovereign will.”

At the end of the funeral, members of Willie’s Sunday school class accompanied the pallbearers carrying the small casket out of the White House to a waiting carriage. The skies opened and the rain poured, and the wind howled, roofs were blown off buildings and homes — as if the heavens were protesting this young boy’s death.

Mary, inconsolable, now having had two sons die, did not attend Willie’s funeral or accompany her husband and oldest son Robert to the cemetery.

That day, Lincoln realized he was just one of many grieving fathers. Thousands of fathers wept that day across the North and the South for sons and some for their president. Moreover, Lincoln now shared something in common with Ellsworth’s father. However, that father did not have the responsibilities of being president and commander-in-chief.

Lincoln had to resume his responsibilities immediately. But he quickly realized he had a young grief-stricken son, Tad, who was unable to find consolation from Mary. Tad had pleaded with her, “Don’t cry mother or I will start crying.”

Lincoln acted

Immediately after Willie died, Lincoln conferred with Dorothea Dix, superintendent of the Union Army’s nursing corps.

“No more amateur nurses. Miss Dix, I want the best nurse you have here caring for my son.” How could Miss Dix respond other than, “Yes, of course, Mr. President?”

Soon Rebecca Pomeroy, a widow, arrived at the White House and assumed the responsibility of Tad’s care. For hours, Lincoln sat on one side of Tad’s bed, while Pomeroy sat across from him. And they talked and cried.

Lincoln wanted details about Pomeroy’s experience. A widow, she had buried one son, one daughter and her husband before the war; now she knew only that George, her surviving son, was “somewhere” in the Union Army. If he were wounded, she prayed that some mother was caring for him as she was for Lincoln’s son.

Sometime during those long hours watching for any improvement, Lincoln asked, “Mrs. Pomeroy, how do you do this work? You don’t know where your son is, you have buried a son, a daughter and a husband, yet here you are caring for my boy as well as the boys down at the hospital.”

“Mr. President, you must go to God and ask him for strength.”

Pomeroy explained that God gave her strength to meet the demands of her days and nights. Then she took advantage of the moment and spoke directly. “Mr. President, you must go to God and ask him for strength.” Their conversations turned to faith on many nights.

Late one night, Pomeroy needed to return to Columbia College Hospital where she had lodging. Lincoln, aware that it was not safe for a woman to be out alone on the streets of Washington, said he would take her back to the hospital. She protested that he needed rest. Surely someone else could do this.

After securing a buggy and two horses, they left for Columbia College Hospital. Washington had had heavy rain; now the dirt streets had turned into mud. At some point, the buggy became stuck. Despite Lincoln’s long experience with teams of horses, he could not “persuade” the horses to pull the buggy free.

The president rolled up his pant legs, swung his long legs over the side of the buggy, and then stepped down into the mud.

“Now, Mrs. Pomeroy, if you will wait here. I will be back.” Turning, he disappeared into the night. As time passed Pomeroy grew anxious. Where had the president gone?

Finally, out of the darkness, the president emerged carrying large flat stones. Deliberately he placed and spaced the stones in the mud.

“Now, Mrs. Pomeroy,” he said, stretching out his hand, “if you will take my hand and step where I point, the stones will hold you. I will get you to the sidewalk without you getting your dress muddy.”

Stone by stone, Lincoln led Pomeroy to the sidewalk. Then he sloshed back to the team. With the buggy lighter, the horses soon pulled it free. Lincoln and the nurse climbed back into the buggy and soon reached Columbia College Hospital.

So, what?

This President’s Day, 2022, might there be a lesson for exhausted pastors, church staff and individuals reading this article 160 years after Willie’s death? Might mud be an analogy for COVID? Sometimes our responsibilities are neither extraordinary nor dramatic but simply making a path for individuals in the darkness, in the mud, to reach safe or safer places.

“Sometimes our responsibilities are neither extraordinary nor dramatic but simply making a path for individuals in the darkness, in the mud, to reach safe or safer places.”

Sometimes ministry requires rolling up one’s pants and getting one’s boots muddied, aware that tomorrow will offer more challenges disguised as interruptions. I think this has been the COVID day-in, day-out experience of many of us.

No few of us have been, using King James Version language, “weary in well doing.” Some have found ourselves mired down “in the mud.” Surely, taking Pomeroy back to the hospital was below the president’s pay grade. Yet, as the hymn writer reminds, “In deeds of love and kindness, the heavenly kingdom comes.”

What happened to Mrs. Pomeroy?

Naturally, one wonders what happened to Pomeroy. Did the president compensate her for those long hours spent at Tad’s bedside? Did she get some medal or official certificate of commendation? How did he reward her for guiding Tad’s recovery? One night the president inquired, “Tell me what you want most, and if it is in my power, you shall have it.”

So, what was her ask? Would the president come to the hospital to “see my boys? Oh, how much good it would do them!”

An artist’s imagining of Abraham Lincoln visiting a Civil War0-era hospital.

That’s it? She asked nothing for herself. On Sunday, May 18, Lincoln arrived at Columbia. Pomeroy was summoned to escort the president “all through” the hospital, including the tents. “Her boys,” whom Pomeroy described as “the lame, halt and withered,” struggled to form into straight lines. Lincoln removed his hat and worked the line, shaking hands with each soldier, asking his name and the name of his regiment and company. Pomeroy wrote a friend, “Such a scene will never be effaced from the memory of the soldiers.”

And Pomeroy, with no hesitation, introduced the president to the hospital’s African American kitchen staff. Despite the disgust of several officers, Lincoln “greeted the help kindly, grasping their hands and asking their names.”

After Lincoln was assassinated, a heart-broken Pomeroy finished her time at Columbia and returned home to Chelsea, Mass. She established a home for indigent women and “quietly lived out the latter days” of her life.

Tragically, she “disappeared” into history. As Erika Holst wrote in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Nurse Pomeroy became “no more than a footnote in the story of Lincoln’s presidency.”

“Although history has largely overlooked Pomeroy” and some historians have mentioned “a nurse” without identifying her, she offered “a cup of cold water” in Jesus’ name. Lincoln summarized her servanthood by describing her as “one of the best women I ever knew.”

Clearly, at a critical moment, a widowed Christian mother ministered to a grief-stricken president, his son and, at times in the future, his wife. Perhaps, before she left Washington she smiled at widely circulated accounts of Tad’s antics such as sitting on his father’s shoulders during cabinet meetings and racing goats down the center hall of the White House.

“At a critical moment, a widowed Christian mother ministered to a grief-stricken president, his son and, at times in the future, his wife.”

In their mutual grief, Tad and his father became inseparable; many nights, his mother emotionally unavailable, Tad fell asleep in the president’s office. Desk work over, President Lincoln picked him up like firewood and carried him off to bed. Father and son slept side by side.

Tad was not, however, with the president those Thursday mornings when Lincoln returned to the Green Room, locked the door, and grieved. After an hour, Lincoln walked to the president’s office and began the soul-draining demands of that day.

Thirty-nine months later, Tad was devastated by his father’s assassination and his mother’s complete breakdown.” Tad described his new status:

Pa is dead. I can hardly believe that I shall never see him again. I must learn to take care of myself now. Yes, Pa is dead, and I am only Tad Lincoln now, little Tad, like other little boys. I am not a president’s son now. I won’t have many presents anymore. Well, I will try and be a good boy, and will hope to go someday to Pa and brother Willie, in heaven.”

Thomas “Tad” Lincoln, age 18, died on July 15, 1971, in Chicago where he lived with his mother; the cause of death was either tuberculosis or heart failure.

Lessons from Abraham Lincoln for grief during COVID

Lincoln understood grief and grieving. He wrote condolence letters as president, a tradition that presidents have continued. But in reading files of condolence letters in eight presidential libraries, I found one Lincoln element absent (except in George H.W. Bush’s condolence letters among the collection). As “condoler in chief,” Lincoln repeatedly wrote, “I want to condole with you” rather than the threadbare passive cliché, “I want to offer you my condolences for your loss.”

Might you borrow Lincoln’s words? Try saying, “I want to condole with you.”

Let us remember that 160 years ago this week, on Feb. 20, a boy died, and the president’s heart was never the same.

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.

Related articles:

Is it time for another Gettysburg Address? | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

Lincoln’s religious influence in forging Emancipation Proclamation still evident after 150 years

What Abe Lincoln tells us about Trump, Biden, guns, God and Falwell Jr. | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Abraham Lincoln, Susan B. Anthony and Adam Sandler: Signs of a church that is more than a museum | Opinion by Brett Younger