Gen Z has the lowest church attendance of any generation and is frequently dubbed as the least religious generation. In a time when churches are struggling to fill their pews, Gen Z is sleeping in on Sunday mornings.

Many are speaking to this topic, as religious leaders everywhere are making bold claims about how to get the next generation through the door. Most of the suggestions center on digital engagement through social media, and several solutions lean into gimmick territory.

“Creating a click-bait church is grossly oversimplifying the needs of the next generation.”

Some of these articles read like a how-to manual on “gotcha” tactics to trick young people into joining a church. Like this one, which says, “10 seconds of boring is enough to lose a Gen Z viewer. Every second of online content you produce needs to add value in an efficient and engaging way.”

The general consensus is: Keep them interested. Your church can’t have a single second of non-flashy “content.” If it does, young people will leave because as a generation raised by the internet, Gen Z is looking for the click-bait equivalent of churches.

While the internet undoubtedly has influenced the way Gen Z thinks, creating a click-bait church is grossly oversimplifying the needs of the next generation.

Defining Gen Z

Gen Z often is defined as being born between 1999 and 2015. The exact dates vary a year or two in either direction depending on the source. As a generation, they can’t remember a world before 9/11. Their school days were interrupted by frequent active shooter drills. During the pandemic, they missed normal celebrations of some of the biggest milestones like coming of age, college graduations and starting their first jobs. They’re entering adulthood in a world that is environmentally and economically uncertain. They are socially conscious and anxiously digital. And they’re the most racially diverse and the most sexually and gender fluid generation America has ever seen.

“Despite the hyper-connective world they grew up in, Gen Z is the loneliest generation.”

And it’s true: They never have known a world without the internet. The overwhelming influence of social media has taught them to see themselves not as a person but as a brand. Numerous studies have researched the ways the internet has mentally affected young people. Despite the hyper-connective world they grew up in, Gen Z is the loneliest generation.

Studies show Gen Z has less in-person contact than other generations as they predominantly interact with a digital world. “Doomscrolling” and a constant barrage of national and world news just a click away create severe isolation.

Even those who primarily use digital media to connect with friends have reported intense loneliness. In response, psychology professor Jean Twenge writes, “There’s something about being around another person — about touch, about eye contact, about laughter — that can’t be replaced by digital communication.”

Even before the pandemic, only 45% of Gen Z labeled their own mental health as “good” or “excellent.” In comparison, Millennials responded with 56%, Gen X with 51% and Baby Boomers with 70%. The American Psychological Association found that 75% of Gen Z named mass shootings as a significant life stressor, along with other issues in the news such as immigration, sexual assault and climate change.

Even before the pandemic, only 45% of Gen Z labeled their own mental health as “good” or “excellent.” In comparison, Millennials responded with 56%, Gen X with 51% and Baby Boomers with 70%. The American Psychological Association found that 75% of Gen Z named mass shootings as a significant life stressor, along with other issues in the news such as immigration, sexual assault and climate change.

Since the pandemic, older members of Gen Z felt heightened stress about their careers as they entered a rocky workforce for the first time. In 2020, one study found 59% of people from ages 18 to 26 experienced unemployment as a result of COVID. Younger members of Gen Z report increased anxiety and depression after they were removed from the social, mental and physical safety of in-person school.

In summary, the kids are not all right.

Community through humor

Gen Z is entering their teenage years, graduating from college and finding jobs in a very different world than the one older generations occupied as they reached these same milestones. However, despite the uniquely tumultuous time, the struggles facing the majority of Gen Z couldn’t be more innate to the human experience — the loneliness and need for physical human connection, the existential questions about life and worries about their economic, social and environmental future.

“They’re finding comfort, or at least coping skills, through absurd humor.”

When faced with similar innate human questions, many older generations turned to community within a church. However, the least religious generation is taking a bit of a different approach. They’re finding comfort, or at least coping skills, through absurd humor.

I don’t mean Gen Z’s humor is silly or outrageous — although it is. I mean their brand of humor is absurdist comedy.

If you’re older than Gen Z and you’ve seen a trending Gen Z meme or TikTok video, you probably were at a loss for words. You might have spent a moment squinting at the image or video and rereading the text, trying to determine how it could be considered funny. And it’s likely the young person with you wasn’t able to fully explain the humor to you in a satisfactory way.

You’re not alone.

Gen Z humor ranges from ridiculous to dark and falls distinctly within the category of absurdism.

What is absurdism?

Most frequently considered as a philosophical theory popularized by Albert Camus, the absurd is the tension between the human desire and propensity to find meaning in life and the human inability to do so in a world that is essentially without purpose or meaning.

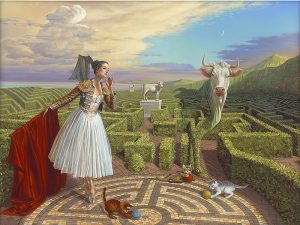

“Echo of Misconception” (2015), Michael Cheval

Camus labeled the Greek mythological figure Sisyphus as an absurd hero who was cursed to roll a stone up a hill in perpetuity only to have the stone fall and roll to the bottom of the hill just before he reached the top. Absurdism is the futile reaching and seeking for something that never will happen or never can be.

Cheerful, I know.

Gen Z has transformed this philosophy into a strange form of humor, responding to existential angst and dread with laughter as a method of coping with their own helplessness to address personal and social issues in a chaotic world.

One Gen Z journalist puts it like this: “When faced with this gloomy concoction of having too many things to deal with and not being old enough or having enough time to tackle them, Gen Z must turn to an alternative to completely throwing in the towel and succumbing to a life of misery and hopelessness: humor.”

“In response to the constant digital updates about COVID, mass shootings, global unrest and national polarization, Gen Z is laughing.”

Studies have proved that Gen Z responds best and relates most to absurdist humor. In response to the constant digital updates about COVID, mass shootings, global unrest and national polarization, Gen Z is laughing.

Making sense of the madness

In an article about meme culture, Ayesha Habib writes, “Perhaps the poignancy of meme humor lies in that Gen Z has no other choice but to embrace the absurdity of the future. … But they aren’t carrying this burden with existential dread. They are using the tool they know best — technology — to lighten the weight with a little levity. … Because if you can’t laugh in the face of your existential dread, what else can you do?”

Some young people argue this kind of humor is beneficial as it helps them confront serious and uncomfortable topics rather than ignore them. However, some therapists are concerned that such dark humor is only trivializing serious mental health concerns.

Regardless of what value society assigns to this brand of humor, one thing is clear. Gen Z is relying on absurdism — not the church or another social structure — to make meaning of the chaos in the world.

Birds Aren’t Real

One of the most popular Gen Z creations of absurdism is a parody conspiracy theory called Birds Aren’t Real.

This fake conspiracy started accidentally in 2017 when then 19-year-old college student Peter McIndoe stumbled upon the Women’s March in Memphis, Tenn. This was shortly after Donald Trump’s inauguration, and counter protesters also were present.

Screenshot from a Vice video about Birds Aren’t Real.

Seeing the aggression from the counter protesters and tension between the two groups, McIndoe took a poster off the street and wrote the three most random words he could think of on the back: “Birds Aren’t Real” and formed his own kind of nonsensical protest, chanting those three words. When the people around him asked what he meant, he made up a conspiracy on the spot, claiming that birds are government surveillance drones designed to film the public.

At the time, he merely wanted to hold a mirror up to the ridiculousness of the counter protesters and didn’t think much about his act until a video of his fake protest went viral, capturing the attention of the internet and young people who thought the protest was hilarious.

As the popularity of this accidental movement grew, McIndoe fully committed to the conspiratorial persona he adopted at the Women’s March. While staying in character, he has been interviewed by various media outlets to spread his made-up conspiracy.

He and his friends made social media accounts, a website and a history of the movement, claiming that from 1959 to 2001 the government systematically killed all the real birds and replaced them with government drones that “fly” around watching us and charge on telephone wires. There’s even merchandise available for purchase, with phrases like “bird watching goes both ways,” “pigeons are liars” and “if it flies, it spies.”

Today, Birds Aren’t Real is a satirical social movement with hundreds of thousands of predominantly Gen Z followers who are all in on the joke. They know it’s a parody, which has only made the conspiracy more appealing to a generation who grew up with a proliferation of far less harmless conspiracy theories.

‘Just seeing chaos’

McIndoe broke character for the first time last year in an interview with New York Times journalist Taylor Lorenz. Dropping the conspiracy theorist persona, he shared the real origin of the movement and reminded people of its satirical nature.

McIndoe also theorized why Birds Aren’t Real captivated the attention of a generation. “I feel like every day, I wake up and open my phone, I’m just seeing chaos. … Growing up alongside the internet, just like Gen Z or anyone my age has just kind of grown up alongside it … there’s no real rules as a society of how to deal with something like the internet. … I think a lot of people feel the madness and don’t really have a way to express it.”

Birds Aren’t Real speaks to a void Gen Z is looking to fill. Instead of falling into despair at the state of the world and the bombardment of information and misinformation, Gen Z is laughing, using satire and absurdism as a way to process the madness.

“Birds Aren’t Real is almost like an igloo in a snowstorm,” McIndoe said. “It’s kind of like a place where people can kind of make shelter out of the same type of material that’s causing the chaos, given that people can take misinformation and use it as a place to safely process misinformation. I think comedy is a very disarming form of communication. … And there’s something about laughing at these things that kind of breaks the illusion of the monster.”

“There’s something about laughing at these things that kind of breaks the illusion of the monster.”

McIndoe is not unfamiliar with this monster. He grew up around misinformation and conspiracies in rural Arkansas with seven siblings in a very religiously conservative family. The children were homeschooled to avoid massive government brainwashing plots such as evolution and homosexuality, which were believed to be part of a “grander government scheme to corrupt the soul of the nation.”

As a teenager he was told he was possessed by a demon after informing his pastor he didn’t believe in God. He described his childhood as one of “ideological loneliness” where he often went to the internet to find a more accepting community or at least differing ideas. Like many in his generation, he feels as though he was “raised by the internet.”

For Gen Z, Birds Aren’t Real is an effort to make sense out of the pandemonium. At the core of this satirical conspiracy is the attempt to respond to the current moment and the strong desire to find belonging.

Again … back to community

Birds Aren’t Real also uniquely speaks to the Gen Z psyche because it gives them a way to find and build community.

Lorenz told The Daily podcast: “A lot of young supporters who I interviewed as well talked about just feeling alone in their communities. … And ironically, when people feel that way, they often turn to real conspiracy movements. But Birds Aren’t Real has kind of allowed teenagers to kind of find meaning and connect in this way through this fake conspiracy.”

Chapters of Birds Aren’t Real have popped up on university campuses around the country, as groups call themselves the Bird Brigade. They gather for social events and attend fake protests against companies like Twitter that use a bird logo.

As the loneliest generation, young people are flocking to internet trends such as this parody conspiracy as a way to find friendship.

(123rf.com)

One common way people find friendship is through their workplace. Except Gen Z is entering the workforce in a time when employers are rethinking the idea of a physical office community, as more and more companies lean into remote or hybrid work.

Recently, the “Ezra Klein Show” discussed ways society is rethinking the workplace since the pandemic. Guest host Rogé Karma conveyed concern about increased loneliness in a future of remote work, noting that historically the workplace has been responsible for much of our in-person social interactions — from casual conversations to friendships to meeting potential spouses.

Karma said, “The office, for all its faults, it was this central institution where you would come together and interact with the same people on a consistent basis. … That’s just not as true for a lot of these other avenues of finding community. … Churches and civic life and volunteer organizations have really declined in recent decades, and I’ve felt that when I tried to go get involved in my community and make connections outside of work. It’s really hard.”

He continued, “My big worry is that if we take away the office without building up some of these other institutions, then the result is just going to be more loneliness, more atomization, more time spent sitting in our apartments alone, doomscrolling on social media, and that seems like a really important social problem to address.”

Karma was worried about increased loneliness and isolation for all work-from-home employees. But particular concern should go to the next generation of workers who already are prone to anxiety, depression, loneliness and who struggle to make connections with people outside of the digital realm.

Where’s the church?

Gen Z is walking into an increasingly remote workforce in a time when, as Karma mentions, churches are declining. On top of everything else the church can provide to the next generation, Gen Z needs a community like the church to replace the social aspects of the workplace that likely will disappear.

Despite increased loneliness, young people are not going to church. Studies from Barna, Pew, Survey Center on American Life and others all come to the consensus that Gen Z is less religiously affiliated and religiously active than previous generations.

However, while young people are not relying on faith communities or faith leaders, Springtide Research Institute found that 71% still identify as religious and 78% identify as spiritual. Young people are not necessarily rejecting religion or spirituality; they are rejecting the church’s way of being religious.

“Young people are not necessarily rejecting religion or spirituality; they are rejecting the church’s way of being religious.”

The church is not speaking to the reality of the world Gen Z is growing up in — a world of uncertainty, loneliness and mental health concerns driven by the digital-based environment we’ve created for them. A world where they’d rather throw up their hands and laugh at the absurdity of chaos than consult with a religious leader for answers.

During challenging or uncertain times, Springtide found, only 40% of young people who self-identified as “very religious” found comfort and help from connecting with a religious community or religious leader. And nearly 50% of young people do not turn to faith communities because they don’t trust the people, beliefs or systems of organized religion.

Gen Z is turning to absurdism and is literally making up fake conspiracy theories to find meaning in the world because religious institutions are failing to fill the gap or meet the essential needs of community that counteract the isolation felt by the loneliest generation.

Being a ‘young adult’ in church today

However, perhaps it’s fair to spread some of the blame. At least partial responsibility surely goes to Gen Z, who doesn’t seem to be making an effort to participate in faith communities. While this is true, more than half of young people said they don’t know how to get connected to a faith community even if they’d like to. And only 10% of young people said they heard from a faith leader or faith community during the pandemic.

I’m a few years too old to be considered a member of Gen Z, but I am what many would consider “a young adult” in church — the target demographic everyone’s worried about leaving religion.

I’ve moved a lot in the past few years, meaning I’ve visited a lot of different churches for the first time. Of roughly a dozen churches spanning multiple states that I visited, I can only think of two occasions where someone talked to me outside of the designated time to pass the peace. Only twice did people in the congregation make an effort to welcome me and extend an invitation for me to get plugged in to the community.

When I read the Springtide statistics about Gen Z not trusting the church in challenging times and feeling unsure of how to get involved in faith communities, I’m not surprised.

And when I read articles about needing to produce interesting content every second of a church service to get young people in the door, I can’t help but roll my eyes. There is a place for innovation and creativity in the ways we rethink our church services, particularly the ways we try to move our services into the present and into ways that connect with younger generations. But I can’t help but feel like we’re making it too complicated and wholly missing the point.

“Perhaps before we devolve into click-bait churches, congregations should simply say hello to visitors and invite young people into the community.”

Perhaps before we devolve into click-bait churches, congregations should simply say hello to visitors and invite young people into the community.

Conversations about keeping young people in church too frequently center around self-preservation. If we stop the fear mongering tactics about a dying universal church long enough, we just might be able to see Gen Z not as potential customers who can save the future of the church, but as people in desperate need of support and community.

Instead of forcing Gen Z into the box that matches congregants from previous generations, the church should meet Gen Z where they are now by responding to their need for support and community in two ways.

First, be the kind of community Gen Z needs.

- Be intentional, invite them to get involved and let them know how to do so. Gen Z is lonely and isolated, and they avoid putting themselves out there for fear of rejection or lack of community. When young people come to church, say hello and go beyond small talk niceties. Extend an invitation for them to participate in your community’s events.

- Be a community that goes beyond the church building. Springtide’s research indicates young people are finding their own methods to explore and express spirituality. Meet them in these spaces. Rather than waiting for young people to walk through the church’s doors and prescribe to your community’s methods of practicing religion, partner with spaces where Gen Z is already looking to find community and spirituality.

- Be present on their journey of seeking. This is a generation of religious seekers. They’re not looking for a community that tells them what to believe. They’re looking to discover it for themselves. Be the kind of community that accompanies them on this path, and ask them as many questions as you answer.

- Be accepting and allow young people to be their full selves in your community. Gen Z is looking for belonging, so don’t give young people a reason why they don’t belong. Springtide found 55% of Gen Z does not attend religious services because they do not feel free to be themselves in that community. Even when Gen Z expresses religion or spirituality in a way different than the majority of your congregants, accept them in your church.

Second, be willing to address the social issues that most concern Gen Z, even when those issues are controversial.

- Be interested in what Gen Z is concerned about. While fighting through a web of conspiracy theories, misinformation, polarization and isolation, Gen Z is grappling with ways to respond to the political and cultural issues of today. They feel inundated by these concerns. Ask questions to discover what is most troubling to the young people in your community and make space to talk about those concerns.

- Be brave enough to discuss controversial and complicated topics. Many people in previous generations have shied away from discussing issues that are too “political” in church. But avoiding these tricky topics isn’t going to cut it for the next generation. Gen Z has no interest in communities that are too afraid to speak about the societal topics that most concern them. Talk about the state of the world and don’t ignore sensitive issues.

- Be real about complexity and don’t default to simple answers. Gen Z is uninterested in every form of fundamentalism and black-and-white responses to the complex chaos of the world. Avoid clichés and settle into uncertainty. Complicated topics deserve more than simplistic answers.

- Be open to a little absurdity. Like it or not, the ethos of Gen Z is absurd. Your community might consider ways not to counteract or replace their propensity for absurdist humor, but to accept it as a coping mechanism for young people. You don’t have to join them on Birds Aren’t Real marches — although you could — but recognize that absurdism has become a useful tool of expression and connection for Gen Z.

Laura Ellis

Laura Ellis serves as project manager for Baptist Women in Ministry. She is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG and previously served in ministry with Safe Havens Interfaith Partnership against Domestic Violence and Elder Abuse. She lives in Waco, Texas, and earned a master of divinity degree from Boston University School of Theology.

Related articles:

Gen Z non-Christians pay most attention to those who live out their faith rather than preach it

She’s Gen-Z, became leery of the church but practices faith with fitness

Most young people are unsettled in the new year but few plan to turn to the church for help