Three new research projects attempt to shed light on the nature of what American churchgoers hear in weekly sermons. The results are predictable, surprising and contradictory all at the same time.

The largest of these surveys was undertaken by Pew Research, which conducted a digital analysis of 12,832 sermons, homilies or worship services delivered between Aug. 31 and Nov. 8, 2020 — the heated runup to the 2020 presidential election and amid the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The representative sample of online sermons was collected from the websites of 2,146 churches.

A key finding: Two-thirds of congregations heard at least one sermon mentioning the election during fall 2020, but how it was mentioned and what language was used varied.

The likelihood of hearing a reference to the election in a sermon also varied significantly among religious subgroups: 41% of Catholic congregations heard at least one sermon mentioning the election, as did 63% of both mainline Protestant and historically Black Protestant congregations and 71% of evangelical congregations.

Two-thirds of congregations heard at least one sermon mentioning the election during fall 2020.

Pew’s report on the study explained: “Roughly half of all evangelical Protestant sermons mentioning the election discussed specific issues, parties or candidates (48%), the highest share among the four major Christian groups. And, in discussing the election, evangelical pastors tended to employ language related to evil and punishment at a greater rate, using words and phrases such as ‘Satan’ or ‘hell’ at least twice as often as other clergy did. Evangelical pastors also were more likely to use the phrase ‘pray (for our) president’ when discussing the election.”

By contrast, historically Black Protestant pastors were by far the most likely to encourage voting and voter turnout: “43% of historically Black Protestant sermons mentioning the election either explicitly encouraged voting or discussed the election in a manner that assumed listeners would vote, roughly double the share of any other group,” Pew reported. “And when historically Black Protestant pastors discussed the election, they tended to use words or phrases related to voting or voter rights — such as ‘suppress(ion),’ ‘early voting’ and ‘register (to) vote’ — more often than pastors from other groups.”

And despite concerns that pastors are now openly endorsing candidates against IRS restrictions for nonprofits — a reality well-documented in a few megachurches like First Baptist Church of Dallas and Grace Community Church in Los Angeles — Pew found “relatively few pastors openly stumped for particular candidates or parties.”

Preaching about the pandemic

Pew’s digital sermon scan also looked for references to the COVID-19 pandemic. It found that worshipers in 83% of congregations “heard at least one sermon touching on the COVID-19 pandemic.”

And those references tended to be longer and more frequent, the researchers explained. “Pastors were particularly likely to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic at some length: 51% of sermons mentioning this topic included references to the pandemic in two or more 250-word segments. And certain groups were especially likely to make the pandemic a recurring theme in their services. Some 56% of sermons by pastors in mainline Protestant churches that mentioned the pandemic (and 63% of those by pastors in historically Black Protestant churches) did so at least twice.”

And those references tended to be longer and more frequent, the researchers explained. “Pastors were particularly likely to discuss the COVID-19 pandemic at some length: 51% of sermons mentioning this topic included references to the pandemic in two or more 250-word segments. And certain groups were especially likely to make the pandemic a recurring theme in their services. Some 56% of sermons by pastors in mainline Protestant churches that mentioned the pandemic (and 63% of those by pastors in historically Black Protestant churches) did so at least twice.”

Preaching about racism

A third topic of Pew’s research was sermon references to racism, a significant conversation point amid a year of police killings of Black citizens, Black Lives Matter protests and a racially tinged presidential election.

Pew found that 44% of congregations heard at least one reference to racism in America in a sermon.

“In discussing racism in America, evangelical pastors disproportionately used oblique phrases such as ‘racial tension.’ Meanwhile, clergy in mainline Protestant and historically Black Protestant congregations tended to discuss this issue using more direct terms like ‘anti-racism’ and ‘white supremacist,’” researchers said.

Pew found that Catholic priests were the least likely of all clergy to mention any of these issues — the election, COVID-19 or racism — in their sermons.

“Fewer than half of Catholic congregations in the database heard a single mention of the election (41%) or racism (32%) during the 10-week study period. And although 69% of Catholic congregations heard at least one mention of the pandemic, congregations belonging to the other three major Christian traditions were at least 10 percentage points more likely to hear messages from the pulpit about the coronavirus.”

Whose sermons are online?

Pews admits in its report that studying only sermons posted online obviously leaves out some percentage of American congregations that do not have the technical ability or the desire to post sermon videos.

This is an issue raised by religion researcher Paul Djupe of Denison University in response to the Pew report. He wrote for Religion in Public that evangelical Protestants are disproportionately likely to post online sermons compared to other Christian congregations, especially Catholic parishes.

This is an issue raised by religion researcher Paul Djupe of Denison University in response to the Pew report. He wrote for Religion in Public that evangelical Protestants are disproportionately likely to post online sermons compared to other Christian congregations, especially Catholic parishes.

Pew’s finding that evangelical pastors were the most likely to mention the election may not translate to an accurate understanding of congregational engagement in elections and political issues, he wrote.

“Every single academic study of clergy (or congregant reports of what clergy said) has come to the opposite conclusion. They all say that Black Protestants and Catholics have the highest levels of political engagement, while evangelical and mainline Protestants have the least.”

Thus, “the difference must lie in who is likely to share sermons online and the competing pressures across religious groups,” Djupe surmised. “Sharing requires literal and figurative bandwidth that some houses of worship simply don’t have.”

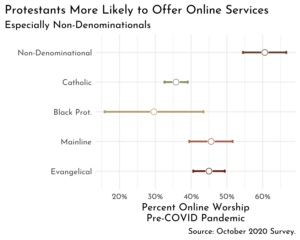

For comparison, he cited an October 2020 study he was involved in that took the opinions of a sample of Americans just before the presidential election.

That survey asked respondents whether their congregations “put worship services online before the coronavirus pandemic.”

That survey asked respondents whether their congregations “put worship services online before the coronavirus pandemic.”

They found that nondenominational congregations (which tend to be evangelical) were more likely than others to have an online presence before the pandemic. “Catholics were the least likely — 25 percentage points less than nondenominationals. Denominational Protestants were online at the same rate — just under half,” he noted.

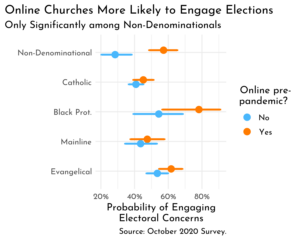

Djupe’s survey also asked whether respondents had heard their clergy address anything from a list of 14 items salient during the election season. Three of those options “explicitly concerned the election (Trump, Biden, and the ‘importance of voting/participating in politics’) and the other 11 covered a range of issues including Black Lives Matter, guns, health care, immigration, poverty, and others.”

To the question of whether churches with an online presence before the pandemic were more likely to have engaged with election issues, Djupe’s answer is a resounding yes.

“Within every group, the churches online had at least a slightly higher engagement with the elections. But it is only statistically significant among nondenominationals. Offline nondenominationals had the lowest levels of electoral engagement, while Black Protestants online had the highest levels. Catholics were on the low end.”

To the question of whether churches with an online presence before the pandemic were more likely to have engaged with election issues, Djupe’s answer is a resounding yes.

A longer look across modern American history

Yet another survey of the content of American sermons came out this fall in a new book, When Sorrow Comes: The Power of Sermons from Pearl Harbor to Black Lives Matter, by Melissa Matthes.

Theologian Richard Lischer reviewed the book in the Nov. 24 issue of The Christian Century.

Matthes, who teaches at the United States Coast Guard Academy, argues that in the aftermath of national tragedies, Americans often turn to churches for solace and that is reflected in the sermons of the day.

A promotion for the book explains: “The sermons delivered in the wake of crises become integral to historical and communal memory — it matters greatly who is mourned and who is overlooked.”

Matthes looks specifically at sermons delivered after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the assassinations of John F. Kennedy Jr., and Martin Luther King Jr., the Rodney King verdict, the Oklahoma City bombing, the Sept. 11 attacks, the Newtown school shooting, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

In sum, the publisher advertises: “She argues that Protestant preachers use these moments to address questions about Christianity and citizenship and about the responsibilities of the church and the state to respond to a national crisis. She also shows how post-crisis sermons have codified whiteness in ritual narratives of American history, excluding others from the collective account. These civic liturgies therefore illustrate the evolution of modern American politics and society.”

“She also shows how post-crisis sermons have codified whiteness in ritual narratives of American history, excluding others from the collective account.”

Lischer commends the study by noting that these nine periods are the kinds of times when even the nonchurchgoers return to church seeking answers or solace, “when the unchurched temporarily return to church and the sanctuary is filled with need.”

In final analysis, Lischer says, Matthes “concludes that the church’s preachers have failed their calling in the face of national tragedy.”

These failures involve both a lack of social analysis and a lack of theological analysis, she contends.

In affirmation of the new Pew study, Matthes finds that historically preachers in times of national crisis have spoken in generalities, such as “evil,” “hate” or “sin,” — as Lischer says “without daring to analyze the historic or social nature of the crisis.”

For example, after the Kennedy assassination, Matthes found a common sermon theme was the danger of hate without defining hate or mentioning racism or anti-Catholicism.

Race — or more specifically the avoidance of discussing race — is a recurring theme of the sermon analysis. Lischer summarizes from the book:

- “After 9/11, white preachers looked to the state to restore America, whereas Black preachers remembered that the state — in the guise of sheriffs, courts, and governors — had helped kill Martin Luther King Jr. and failed to do justice for Rodney King.”

- “In Los Angeles, the police officers who struck Rodney King with batons more than 50 times were acquitted. In the aftermath of the trial, most white preachers did not address this savage mistreatment of King, focusing instead on the rioting and looting that followed the verdict.”

- “After the Oklahoma City bombing a few years later, the murderer Timothy McVeigh’s whiteness was not interrogated in pulpits in the same manner as King’s blackness had been.”

And lest anyone think this is an entirely new phenomenon, Lischer reminds in his review that in November 1941, the Roosevelt administration circulated a suggested sermon outline in support of the undeclared war effort, with the hope that the nation’s clergy would do the White House’s pro-war bidding.

Yet despite not taking FDR’s bait, most American pastors still spoke of the declaration of war as though they were, in fact, agents of the state.

“In response to Pearl Harbor the following month, preachers did not eulogize the victims, exegete their own feelings about the attack, or attempt a theological explanation of the event or its motives,” Lischer said. “They spoke of the coming war as a matter of obvious fact. In their rush to associate the church with the U.S. war effort, mainline preachers, despite Reinhold Niebuhr’s Christianity and Crisis editorial to the contrary, were largely silent about the subsequent internment of Japanese citizens in fenced ‘exclusion zones.’”

Related articles:

Preaching the ‘red letters’ often makes congregations red in the face | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

In praise of political preaching | Opinion by Alan Bean

Preaching is inherently political — but not partisan | Opinion by Andrew Gardner