I wonder how many congregations have taken time during this pandemic to consider their aesthetic. As worship services and other educational or community programming have transitioned to online formats, how have our ideas of beauty changed or remained the same?

I wonder how many congregations have taken time during this pandemic to consider their aesthetic. As worship services and other educational or community programming have transitioned to online formats, how have our ideas of beauty changed or remained the same?

In his work Stranger’s Below: Primitive Baptists and American Culture, historian Joshua Guthman identifies a “lonesome sound” in the music of Primitive Baptist congregations that he suggests characterizes a Primitive Baptist aesthetic. This sound transcended their harsh reformed theology and doctrine, capturing a disposition of ambiguity and uncertainty that typifies our human existence.

Primitive Baptists emerged in the wake of what historians refer to as the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century. They challenged evangelical and missionary denominational groups, whom they considered arrogant. They preached that only God could save. Attempts to influence the salvation of others through missions, books and preaching were all futile.

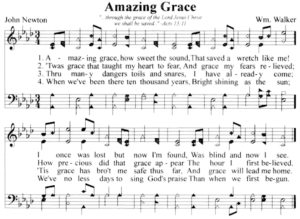

These often-poor Appalachian and Southern congregations split off from missionary minded Baptists. Their worship included the singing of shape-note tunes and when hymnals were in short supply, a leader would line the hymns — singing a line that would be echoed by the rest of the congregation. Sermons often took on a song-like quality. Guthman identifies similar trends in Black Primitive Baptist congregations in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Shape-note version of “Amazing Grace” from an old hymnal.

While Primitive Baptists congregations experienced decline like many denominational groups in the 20th and 21st century, Gutham suggests that their “lonesome sound” remains a part of the broader American culture. The late Ralph Stanely’s performance at the 2002 Grammy Awards of the dirge “O Death” from the soundtrack of the movie O, Brother Where Art Thou serves as one, now popular, example of this Primitive Baptist aesthetic.

As I listen to worship services on my computer screen, void of the pomp and circumstance of communal singing, I see beautiful musical offerings from families and individual singers and instrumentalists. Such an aesthetic difference reminds me of Guthman’s idea of this “lonesome sound.”

Perhaps our time of physical distancing in 2020 gives us an opportunity to think about what constitutes beauty in our particular Baptist experience.

Our aesthetics will indeed be particular because, as Baptists, we champion the idea of local church autonomy. While we often think of this autonomy as an issue of doctrine and authority, it also is one of aesthetics.

Local church autonomy opens congregations to the possibility of adopting the aesthetic ideals of their local context. No Baptist groups demonstrates this better than the Evangelical-Baptist Church in the Republic of Georgia. Recognizing that Western European and American aesthetic ideals would not translate to Georgian culture, Baptists in the Republic of Georgia adopted some of the aesthetics of their local culture, heavily influenced by the Orthodox Church.

Baptists in Georgia experience worship with incense and iconography. The denominational group also has a system of leadership that includes bishops, and it is not uncommon to see congregational leaders in ornate robes.

There is a decidedly different aesthetic between Baptists in the United States and Baptists in the Republic of Georgia. This difference, however, has not kept Baptists in Georgia from forming strong partnerships with groups in the United States, like the Alliance of Baptists.

“Our conception of aesthetics does not need to be limited to worship either.”

Our conception of aesthetics does not need to be limited to worship either. For myself, when I think about the Baptist aesthetic of my childhood, I think about a Wednesday night potluck — a table set with an uncountable number of dishes with various casseroles, colorful and fragrant.

There is a beauty in watching everyone construct their plate and join tables of their friends and loved ones to share a meal.

Perhaps we think about the aesthetics of a baptism. The baptistry in the church I grew up in was adorned with what I am certain some would consider tacky wallpaper depicting the Jordan River. For my congregation, however, this wallpaper provided an aesthetic link between my baptism and the baptism of Jesus. Such an aesthetic differs from an outdoor baptism or even a baptism in a plain baptistry.

As many congregations are now well-practiced in virtual worship, perhaps we can take a step back to consider our Baptist aesthetics anew. How have we translated our in-person ideals of beauty to a digital format? What elements of our congregational aesthetics have been lost? What new ideas of beauty have we gained?

Nurturing a congregational aesthetic functions as a means of building and reinforcing communal identity, as groups like the Primitive Baptists demonstrate. It pushes beyond intellectual doctrine and ideals that bind congregations together in order to appeal to shared emotional and affective ideals.

In a world ravaged by COVID-19, famine, white supremacy and greed — among other things — perhaps pausing to consider what we as Baptists find beautiful would provide congregations the imaginative energy to dream new futures. If we can see, and taste, and smell, and hear, and feel the kingdom of God, we might better be able to imagine it on earth as it is in heaven.