I once thought grace was pretty amazing — Jesus dying on the cross, all my sins forgiven, a guaranteed place in heaven after I died. But what if grace is even more amazing?

As a child I learned about “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me” and that grace was “God’s Riches At Christ’s Expense.” I was told I was “saved by grace, not by works” and that this grace canceled out the sin(s) I committed before I was “saved” and then secured my soul after death. I gratefully embraced this introduction to the pathway of faith, ready to learn and grow.

J. Claude Huguley

But life kept happening. Faith must be lived, and I would occasionally mess up (nothing big, I was only 8) but enough in my mind to qualify as “sin.” What was I to do? I had been told the record of my past sins had been cleared and my future in heaven was still secure, but what was to be done with these new sins now added to my ledger?

The prescribed solution was to confess my sins to God, be sorry and through God’s grace these new sins would be wiped away as well, re-securing my place in heaven. While the teaching of “once saved, always saved” relieved some of the angst about losing my salvation, an element of felt risk remained.

“Unfortunately, these efforts at being too good to need grace did not teach me much about grace.”

I redoubled my efforts to be “good enough” with the goal that I might work so hard and be so good that grace never would be needed. Unfortunately, these efforts at being too good to need grace did not teach me much about grace but instead cultivated pride, a hypervigilance about sin and a judgmental spirit toward myself and those around me. My judgments allowed little room for grace in relation to me or anyone else.

What had I missed about grace?

Like many believers, I was seeing grace through a works-based lens. Grace was God’s “work” (at Christ’s expense) and in this transaction my (our) responsibility (work) was to ask, accept and receive it. I understood this work of grace had been introduced by God after human sin had broken relationships with God, fellow humans and the whole creation. I believed sin came first — grace followed. This work of grace was thus God’s merciful reaction to human failure, disobedience and imperfection.

“This more amazing grace of Jesus is his way of being in the world, proactively reaching out, ready to embrace the sinner even while they are still sinning.”

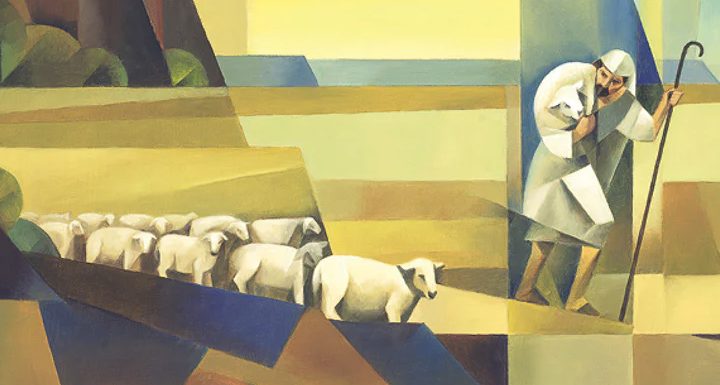

This way of framing grace remains powerful, bringing comfort and meaning to many. But I have come to wonder if the grace Jesus teaches and New Testament writers present is something even more amazing. This more amazing grace of Jesus is his way of being in the world, proactively reaching out, ready to embrace the sinner even while they are still sinning. The “lost” parables in Luke 15 (lost sheep, lost coin, lost sons) reveal the substance and reach of this grace.

The third and most familiar of these parables is commonly known as The Prodigal Son. It provides Jesus’ clearest description of God’s grace in action. For a long time, my reading narrowly focused on the audacious younger son’s leaving home, totally messing up, coming to his senses and then experiencing grace when he returns back to the father. While meaningful, is this sonship restoration and the celebration that follows the only picture of grace in the story?

Hardly. A broader reading unveils a far more comprehensive and amazing grace, permeating and overflowing in the story from beginning to end. It is an ever-present flood of gracing love toward each beloved.

There is grace in the father’s trust when the self-absorbed son wants to leave home. There is grace in the consequences resulting from the son’s selfish choices and then in the spiritual awakening they nurture, fueling his desire to return home in humility. There is grace in the father’s hopeful waiting with a ready embrace for the son from the day he left, the seeing him from afar, and the running to meet him with that embrace. There is grace in the father’s going outside to the pouting elder brother and the invitation for him to join the celebration of grace and trust.

“Grace is everywhere if we have the eyes to see it.”

There also is grace in the shepherd going after the lost sheep, finding it and carrying it on his shoulders with joy. There is grace as the woman searches for her lost coin, finds it and rejoices with her neighbors. There is grace in the joy and celebration of each found beloved and the gracing community that joins in that celebration. Grace is everywhere if we have the eyes to see it.

Is this not a more amazing grace?

This amazing grace flows from a merciful God of love whose essential character is love and giving. One cannot fully speak of the God of Jesus without also speaking about grace — they are inextricably connected. This God of love empowers and eternally displays grace. More than just a reaction to human sin, grace always has been and always will be. Grace’s first action was creation, and grace has been active from the beginning.

Indeed, Jesus’ death and resurrection is not the activator of grace; it is the most high, deep, profound and embodied expression of that grace!

As a part of creation, we humans — individually and collectively — are recipients of this grace. It is an unearnable gift of God, given before we existed, inviting us into the God-ordained community of grace and love. We can deny it, fight it, abuse it, run away from it or lose our felt connection with it, but we cannot extricate ourselves from this grace that will not stop pursuing us with love.

“Grace believes in us, knowing all we have been, are and can be, and still loves us again, again and then again.”

Grace believes in us, knowing all we have been, are and can be, and still loves us again, again and then again until we are ready to embrace our most grace-full self within that community of grace and love.

But is this persistent, pursuing grace just wishful thinking and too good to be true? Wouldn’t a grace like this be enabling bad choices and harmful behaviors, excusing hurtfulness and allowing an avoidance of accountability? What about the terrible hurts we give each other and receive as individuals? What about the horrors of genocides like the Holocaust or systemic racism, economic and sexual exploitation or the inhumane acts of warfare that impact generations and draw whole societies into the exercise of their evils?

Does grace just overlook and excuse evil?

Absolutely not! Grace knows “hurt people hurt people” — every perpetrator of new hurts is acting out an unhealthy and destructive response to an unresolved wound of their past. We see examples of this in the physical and sexual abusers of children; many had their own horrific experiences of abuse in their own childhood and they pass their awful wounds on to a new generation of children. Knowing “hurt people hurt people” does not diminish the hurtfulness of the present act but does identify its deeper roots and pinpoint the places where grace intervenes.

Most hurts — whether physical, emotional or spiritual — are hurtful because they tell us we are worthless. A harm is inflicted or something of value is taken away and the receiver of this action feels diminished, disrespected or disheartened; their sense of worth and security is threatened or destroyed.

“Wounding others does little to resolve anything; it just adds to our own personal woundedness and the woundedness of the larger world.”

Whether “perpetrator” or “victim,” all carry wounds crying out for attention. These wounds spark a desperate search for some resolution for the felt sense of having less worth or no worth at all. Of course, wounding others does little to resolve anything; it just adds to our own personal woundedness and the woundedness of the larger world.

In this world of overwhelming woundedness, grace reaches out to heal each wound in each person — the old wounds that triggered the perpetrator’s hurtful act and the new wounds created in the perpetrator and the victim by this new transgression. Grace sees and knows the full depth and reach of every hurt, never looking away, but seeing the hurt in the fulness of its awfulness. Grace acknowledges the stark reality that the hurt that was done cannot be undone and the fact of any hurtful act will not change.

But grace still intervenes, with grace. Grace gives opportunity to change the meaning of what happened for everyone involved. It uncouples the connection between the act of wounding itself and the worth of the person(s) who did the wounding or received it. Grace continues to assert the inherent worth of each beloved, believing in each person impacted, and seeing possibility, renewal and fruitful living as grace is given and received.

As a truly life-giving gift, grace seeks to restore the never known or forgotten consciousness that we are beloved now and always. Nothing we do or don’t do and nothing that is done to us will make us more or less loved. Grace reaches out a helping hand, gracing each beloved with what they need to join (or rejoin) the community of grace and love.

The shape of grace may look different for each recipient, providing what is needed. Grace does not mean that the one who murders goes free; grace for that person may be the consequence of a lifelong incarceration. This time of restriction gives opportunity for this person to receive grace for the healing of the original wounds received before the murder as well as time to bring about genuine remorse and gracing actions toward everyone impacted by the murderous action.

Grace for the ‘impacted ones” may include an awareness that this hurt and every hurt is fully understood. This makes possible comfort for their grief and anger, power to forgive other and self, and the energy to address the structural and societal issues that lay the groundwork for each hurtful event. Even the one whose life was taken prematurely is embraced by this grace that reaches out beyond the grave.

We all need this amazing grace. It becomes available to all who recognize they need it and accept that everyone around them needs it too. We are all wounders and wounded, hurtful and hurting. The community of grace (kingdom of God?) is inhabited by those who see and understand they are living in constant need of grace, not condemnation.

There may be great diversity in the ways we “miss the mark” or “fall short” but no diversity in our need for grace to pick us back up, again, again and again.

What might happen if each of us embraced our vulnerable need and this amazing grace, allowing it to embrace us?

We would see more grace. A beautiful sunset, a tender smile, a word of encouragement, a welcome embrace, or healing relational connection — experiences of awe, joy, sadness, laughter and love. A roof over our head, nourishing meals, sources of transportation, opportunities for education, growth and meaningful work. We might begin to see glimpses of grace in health challenges, difficult relationships and personal failures and regrets.

“Grace is all around us.”

Grace is all around us. In the midst of the seemingly good, bad or indifferent, grace gives comfort through pain, strength through weakness and hope through difficulties or despair, repairing, renewing, redeeming. Gratitude freely flows when we see the gifts of grace all around us.

We would be more grace — welcoming, encouraging, accepting, trusting, healing, forgiving toward others and ourselves. Offering more of our own imperfect acts of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. More vulnerable, more grateful, more humble, more real.

Is this not amazing grace? May we see more grace and be more grace in the living of our days.

J. Claude Huguley is a son, brother, husband, father and grandfather who has served as a hospital chaplain for more than 30 years in Nashville, Tenn. He is the author of a new book, Trusting Grace: The Journey from Fear to Love. He and his family are members of Immanuel Baptist Church in Nashville.