In my home state, folks make regular pilgrimages to a revered shrine where they engage in rituals, sing songs, pray, engage in charismatic hand lifting, and often speak in mysterious tongues indiscernible to outsiders. Sometimes adherents express the ecstasy of praise. Sometimes they smite themselves on the head and chest, expressing grief as if they were attending a tragic funeral.

Yes, University of Tennessee football games at Neyland Stadium can be quite an experience of fervency. It’s not just Volunteer fans, though. The same applies at all stadiums and concert venues — from Bama to Berlin to Beijing and all points in Benin.

In my experience as a professor, undergraduate students struggle to put into words how events like football games and concerts are not religious. With rituals, singing, prayer and fervent devotion, how are such events not religious? Some students say the focus of football games and concerts is not to honor or commune with God.

However, some branches of Hinduism are atheistic. Is Dharmic Hinduism not a religion because adherents don’t believe in a god?

Students typically reply: “No. But … but… .” They sense a distinction between a football game and a religious endeavor — whether theistic or atheistic — but they struggle to put it in words. So, how do we distinguish the purpose of bleachers versus pews (so to speak)?

Tennessee Fans in the student section during a game against the East Tennessee State University Buccaneers at Neyland Stadium on September 8, 2018, in Knoxville, Tennessee.( Photo by Donald Page/Getty Images)

What is ‘religion’?

To parse this, let’s first break down what the word “religion” literally means, and then we’ll examine the practical application.

“We keep using that word, even though it means more than we think it means.”

I made it through four years at a Baptist university and three-and-a-half years at a Baptist seminary without learning the literal meaning of “religion.” It’s not just me. During a conversation with some fellow professors, I referenced the literal meaning of religion. One colleague with multiple degrees in religious studies said he’d never heard it either (as did an internationally known religious leader who reviewed an earlier draft of this essay). Inconceivable! We keep using that word, even though it means more than we think it means.

Indeed, I didn’t learn the literal meaning of the word until I taught Introduction to World Religions. Our textbook was the sixth edition of Michael Molloy’s Experiencing the World’s Religions. In the opening pages he addresses the etymology of “religion.”

Low and behold, the l-i-g in religion comes from the same root as the word ligament. What do ligaments do? They connect. Thus, to practice re-lig-ion is to reconnect.

But reconnect with what? Arguably, people at a stadium reconnect as fans. They also reconnect to their team or to the singer they adore, especially if the singer is swift at supporting their chief team.

So, the fans are connected to themselves and the event. However, mere social connection doesn’t capture what we mean by religion. For an experience to be religious in the purest sense, we are not reconnecting on just the horizontal plane of human interaction. A truly religious endeavor also seeks to reconnect vertically to what is commonly called a “higher power.” In this sense, religion involves exploration of big-picture questions regarding where we came from and where we’re going.

Thus, what distinguishes a football game from a religious experience is that disciples of a religion seek to connect with the source and destination of life.

Spiritual connection

Two 20th-century theologians captured this in their signature phrases. Rudolph Otto spoke of spiritual connection as the experience of awe with “the mysterious tremendous and fascinating.” Paul Tillich spoke of “the ground of being” — the supreme creative order. Regardless of how any of this is understood, for most theists, the vertical exercise of religion seeks to connect the individual with a supreme power who set creation in motion, sustains us in the present and will continue like a nurturing parent for eternity-future.

However, here’s a hiccup for the common understanding of religion. If we specify that religion is focused on communing about and with the source of and destination of being, it’s easy to limit religion to what’s going on at a church, mosque, temple or synagogue. However, let’s imagine next door to one of these sacred sites, a group of secular humanists has gathered. When they systematically contemplate a strictly mechanistic formation of life via evolution and that we are all headed back to the cycle of nothingness and big bangs, they, also, are engaged in the practice of religion because they are seeking to reconnect with ultimate mystery.

As mentioned, viewing religion as literally meaning “reconnection” offers practical application. How so? It promotes both healthy spirituality and behavior. In seeking reconnection, we admit we are cut off from full knowledge by mystery. This humbles us — a necessary quality for sincere growth. Furthermore, remembering that the l-i-g in religion is from the same root as ligament reminds us that we and others suffer spiritual injury and that we are all capable of causing spiritual injury. Female athletes who have given birth and had a torn ACL have said the torn ACL was worse.

Wounded people

Now, get this. ACL stands for anterior cruciate ligament. The word cruciate means “shaped like a cross.” This shape not only symbolizes Christianity. It also brings to mind the torture of Jesus prompted by religious leaders and some of their followers. Sadly, it also reminds of the pain subsequently inflicted in the name of Christ — from the Crusades to sexual predators to overly dogmatic parents. Even if we haven’t suffered abuse, we all have a torn ACL of the soul.

“Even if we haven’t suffered abuse, we all have a torn ACL of the soul.”

Throw wounded people together and we often perpetuate the wounding rather than promote healing. For instance, I’m dedicated to the historic Baptist principle of separation of church and state, which Colonial Baptists labored at great cost to establish. At a county commission meeting in Tennessee in 2001, I spoke against posting the Ten Commandments in the lobby of government buildings if people of other faiths were not allowed to post their own expressions. The next day, my family and I came under social attack. We were shunned and our jobs threatened. In fact, one of my family members was suspended and nearly fired from the Christian school where they worked. One student’s father angrily said to me, “I will not have my children taught by the (family member) of a man as unpatriotic as you.”

Nearly 20 years later, I was in conversation with several of the now-adult former students of that Christian school. One person said, “Yeah, I found out later, the whole time that was going on, my father was an alcoholic and having affairs.” Another said, “Right after all that, my dad lost his job for embezzling from the company.” Yet another said part of the reason she became an atheist was because she was so disillusioned by the contrast between her parents’ public behavior and the harshness of their “arrows in your quiver” parenting.

As a therapist, almost every one of my workdays I encounter people with deep wounds because of abusive pastors or parents who carry out their abuse in the name of their religion. There is a reason Christian Scripture contains a story of Jesus turning over the tables of those using religion to exploit others. There is a reason Jesus said if someone harms a child’s spiritual development it would be better for the one causing harm to have a millstone tied to their necks and be cast into the sea.

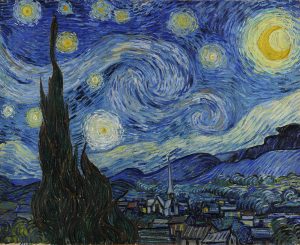

“Starry Night,” Vncent Van Gogh, 1889

Disconnection

In his book How to Know a Person, David Brooks dedicates a chapter to the epidemic of disconnection in modern culture. As evidence, he cites tremendous increases in depression, suicide and loneliness. He postulates several possible causes. One suggestion is that a decline in religious activity correlates with the increase in a soul-sick society.

Thus, the ebb and flow of religious revival leading to abuse of power leading to disillusionment continues. It’s not a new story. I once watched a Sunday school video series hosted by Methodist pastor and author Adam Hamilton. He told the backstory of Van Gogh’s painting “Starry Night.” I now have a deeper appreciation of that painful testimony in paint. In the foreground, the top of a tree makes a triangle shape reaching to the sky. This is echoed in the midground by the shape of the village church’s steeple. While there are lights in most of the village windows, the church is dark. Van Gogh had tried to become a pastor like his father but was deemed too weird. He felt rejected. Church was a source of pain for him, not nurture.

Maybe in response to the nastiness of organized religion, I’ve heard several folks say, “I’m spiritual but not religious.” I think what they mean is they don’t follow a particular organized denomination. I respect the sentiment. I went through a time in which I wouldn’t be going to church if I weren’t an employee. I’m no longer an employee of a church nor a denominational university that expects church involvement, but I know I need connection both vertically and horizontally.

I strive to remember how Jesus, Martin Luther, Mary Dyer, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and so many others were harmed by religious bureaucracies of their day. Nevertheless, they persisted. Despite the behavior of others, they engaged in congregational connection. They were true to the prescription of Hebrews 10:24-25, “not neglecting the gathering together … but encouraging one another.”

‘Lars and the Real Girl’

We today need to continue to call out the abuses of bureaucratic religion. We also must avoid letting gross sins reported in headlines distract us from the thousand little ways we create stumbling blocks. Our spirituality is empty without the spirit of James 1:27. The passage addresses both vertical and horizontal connection with this prescription for torn spiritual ligaments: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself unstained by the world.”

In many college classes, I have shown the beautiful film Lars and the Real Girl. (Juno was a great movie, but the 2008 Oscar for best original screenplay should have gone to Lars.) Lars has apparently had a mental breakdown, and his very odd behavior is raising eyebrows. In one particularly realistic scene, the church council is debating what to do about Lars. An advocate for Lars points out — in painful detail — some of the oddness of each of the council members. Still, the harshest critic rhetorically asks if Lars and his particularly odd behavior will be allowed in church. The pastor’s response is so simple yet profound, and the subsequent resolution, even if fanciful, rings true and begs imitation. (No spoiler. See the movie.)

I’ve had students say, “I couldn’t wait. I rented the movie last night and watched the ending.” Whether in human development or religious studies classes, I ask, “What if we as communities — what if faith groups — responded to people’s pain and oddities the way the people in this film responded to Lars? What if we reconnected and then helped others reconnect?”

Then, from another movie addressing vertical and horizontal reconnection, Yoda hears us ask, “What if?” He flares his eyes and says, “Do or do not. There is no try.”

Indeed, we can help each other heal the torn ligaments of the soul. There are many local “rehab centers” where we can join fellow limping pilgrims as our soul ligaments reconnect within ourselves, with others and with awe-inspiring mystery.

We can’t be forced to reconnect vertically and horizontally, anymore than we can be forced to attend a football game and be sincere in our cheering. No, when it comes to true religion that reconnects our inner and outward divisions, we must Volunteer — for such a Tide as this.

Brad Bull

Brad Bull was baptized into the Christian faith and later into attendance at University of Tennessee football games at age 7. Per a ritual prescribed by his therapist, one of his most profound spiritual experiences happened while screaming a prayer from Knoxville’s Henley Street Bridge. Fittingly, the bridge reconnects the banks of a river, from each side of which a Civil War battle was fought. During his prayer, Neyland Stadium was just downstream. Up the hill to his right was his young-adulthood’s nurturing congregation, First Baptist Church. He has served as a hospital chaplain, pastor, university professor and now as a private practice therapist in Tennessee and Virginia. His counseling and retreat services can be reached at DrBradBull.com.