By Marv Knox

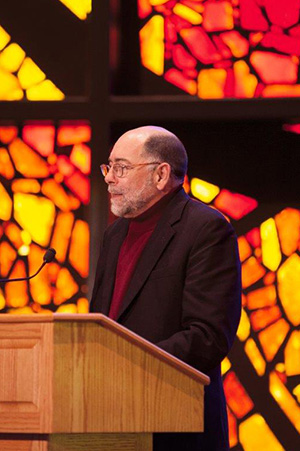

Jesus’ perspective on economics can be up summed in four words — “What’s mine is yours,” New Testament scholar Hulitt Gloer stressed during the annual T.B. Maston Lectures in Christian Ethics.

And while such a standard may seem impossible, “with God, all things are possible,” insisted Gloer, the David E. Garland professor of preaching and Christian Scriptures at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary.

Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon School of Theology and the T.B. Maston Foundation sponsor the lectures each spring to honor the legacy of Maston, one of the premier Baptist ethics professors and authors of the 20th century. Gloer examined “kingdom economics” presented by the New Testament writer Luke.

Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon School of Theology and the T.B. Maston Foundation sponsor the lectures each spring to honor the legacy of Maston, one of the premier Baptist ethics professors and authors of the 20th century. Gloer examined “kingdom economics” presented by the New Testament writer Luke.

“Luke saw kingdom economics as a foundational issue for the Christian life,” Gloer insisted. “To borrow a cultural truism, Luke understood that ‘money talks.’”

Luke consistently presents two intertwined themes, he said: The gospel can be presented in economic terms. And with God, nothing is impossible.

Those themes surfaced when Mary learned she would become the mother of Jesus, Gloer noted. Three times, Luke reported Mary was a virgin, emphasizing Jesus’ birth was impossible from a human perspective.

“Everything associated with Jesus and the kingdom are beyond the confines of reason,” he said. “Don’t expect either Jesus or the kingdom or the things Jesus calls his followers to do to be reasonable.”

Still, Mary responded to an “impossible” proposal with total acceptance. She told the angelic messenger, “Let it be to me according to your word.”

That story sets the tone for Luke’s emphasis on “kingdom economics,” he said, paraphrasing Mary’s response in economic terms: “What’s mine is yours.”

Early in Jesus’ ministry, he preached from the Prophet Isaiah to the synagogue in his hometown, Nazareth, Gloer recalled. Quoting from Isaiah 58 and 61, Jesus compared his ministry to the Old Testament’s Year of Jubilee.

“What are the ‘big three’ concepts of the Year of Jubilee?” Gloer asked. “All debts cancelled, all slaves freed, all property returned to the family of original ownership.”

Such a notion presented profound economic consequences, he observed. “It would have required a radical upheaval of the social fabric, a community revolution which would have resulted in … blessings to the poor [and] the hungry, and weeping and woes to the rich, the satisfied and those who are content to eat, drink and be merry.”

Conversion necessary

Fulfillment of Jesus’ vision requires conversion, complete with economic implications, Gloer added.

“The good news has got to get from our heads, to our hearts, to our wallets,” he said. “It might just require such a whole new willingness to approach others and to say, ‘What’s mine is yours.’ And that seems unreasonable, unrealistic, impossible.”

Throughout Luke’s Gospel, Jesus advanced that theme, Gloer noted. He cited at least 14 examples — from the parable of the Good Samaritan to the conversion of the tax collector Zaccheus — each involving economics, and most involving sacrifice.

“Do you see a pattern here?” Gloer asked. “These [economic responses to the gospel] seem unrealistic, impossible. While they might be painful, they’re not impossible, because with God, all things are possible.”

Jesus also illustrated the “kingdom economics” theme when he reinterpreted the Passover at the Last Supper, he said.

Jesus broke the bread and said it represented his body, and he poured out the wine and said it represented his blood, he noted, recalling, “Jesus said: ‘What’s mine is yours. I give my all for you.’”

The early church took Jesus’ “kingdom economics” seriously, Gloer added.

Twice in the book of Acts, Luke reported Jesus’ followers sold their possessions and shared all they had in common so none did without, he said.

Tucked in the second account of “a community of giving, of sharing,” Luke wrote: “With great power, the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus. And God’s grace was so powerfully at work in them all,” he noted.

“The power of the apostolic community was power predicated upon the matter of community,” Gloer asserted, stressing Luke’s close connection between selfless sharing and divine power.

“Money talks. It always has,” he said. “What’s your money saying? Is it ‘What’s mine is mine; what’s yours is mine”? Or is it kingdom economics: ‘What’s mine is yours,’ so that the needs of everyone can be met?”