Lost among the big headlines of the June Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting — headlines about creation of a Sexual Abuse Task Force, a hotly contested presidential election and resolutions on Critical Race Theory and abortion — was a consequential motion not widely understood in its scope or history but suddenly prescient.

That motion was made by Jay Adkins, a pastor from metro New Orleans. It stated: “In light of concerns raised by legal counsel and seemingly contradictory opinions about matters facing the convention, I move that this body request that the Executive Committee study and report back to this convention at the 2022 annual meeting the question of whether or not there is an inherent conflict of interest with the convention and the Executive Committee being represented by the same legal counsel.”

Jay Adkins

Now that the Nashville law firm that has represented both the convention and the Executive Committee since 1966 has announced it is ending that relationship, the Adkins motion appears more relevant than ever. And it is in that context that the day after the law firms’ announcement, Oct. 12, Adkins wrote on the SBC Voices website a full explanation of what he intended by his motion that was referred to the Executive Committee for consideration.

He favors one legal counsel but not this one

“Let me be clear. Ultimately, it is my position that the legal counsel of the Southern Baptist Convention SHOULD be that of the Executive Committee. Because the EC should be functioning as a servant of the SBC … not as its overseer (advising against the will of the messengers),” he wrote. “If the EC would take on its assigned tasks (and that alone) then I believe it is right and good and helpful for both to share counsel.”

However, the “overreaching way” the Executive Committee has been functioning and “the cover provided by legal counsel” were the impetus for the motion, he explained. “The concerns many of us have regarding this conflict of interest would disappear if there were no actual conflict taking place between the will of the messengers and that of the EC and if we had new legal counsel who served us and did not try to manage our cooperative work. With the resignation of Guenther, Jordan and Price I am now hopeful such a course correction might be realized.”

What happened in the weeks after the SBC annual meeting is that Guenther, Jordan and Price — along with additional lawyers hired by the Executive Committee leadership — worked to convince the Executive Committee not to follow a key directive issued by convention messengers but to, instead, declare their duty to the Executive Committee above their duty to the convention. This precipitated the most severe test of Southern Baptist polity since the denomination’s founding in 1845.

‘A Counsel Crisis’

By Adkins’ account, the drama that played out with the Executive Committee meeting three times in three weeks to wrestle with the question of whether to waive attorney-client privilege in the investigation of an alleged mishandling of sexual abuse allegations was only a public version of what has been transpiring behind the scenes for years.

“We have had what I will call a Counsel Crisis for some time now.”

“We have had what I will call a Counsel Crisis for some time now,” he said. “It’s been years in the making in my estimation, hence the reason for the motion, but the culmination for me was after the motion was made when the EC hired a second high-powered D.C. law firm to advise the EC to act against the will of the SBC messengers to waive privilege after our own long-time law firm also advised the trustees to act against the will of the messengers and to vote against the waiving of privilege. Then the EC hired a third law firm to investigate the substance of my motion regarding whether or not there is such a conflict of interest.”

Again, lost amid the national headlines of the Executive Committee’s debate over the sexual abuse investigation during its Sept. 20-21 meeting in Nashville was the fact that Adkins traveled from New Orleans to Nashville to speak on behalf of his June motion.

“Many of us have been deeply concerned about certain actions of the EC for a number of years and the apparent cover provided through recommendations received from our attorneys,” Adkins wrote on the blog. “My personal concerns go back to the sole membership issue and the scuttlebutt at that time that some at the EC had apparently suggested that the convention consider shutting down one of our seminaries.”

Adkins charged that the Executive Committee — which is tasked with carrying out the work of the convention between annual sessions — has instead become the tail that wags the dog.

“Over the last couple of years, it has appeared to many interested Baptists that the EC has stepped over its ministry assignment boundary lines,” he explained. “Ultimately, it appears to me that our legal counsel has helped to enable this shift in the essence of the EC from servant of the convention to its overseer. This is NOT the way.”

“Ultimately, it appears to me that our legal counsel has helped to enable this shift in the essence of the EC from servant of the convention to its overseer.”

‘A convention of churches, not lawyers’

Adkins published the full text of his comments to an Executive Committee subcommittee during the September meeting.

Among his statements, he noted he had not understood the number of lawyers the Executive Committee employed or would come to employ, just as he did not understand the number of lawyers serving as trustees of the Executive Committee.

“We are a convention of churches, of course, NOT a convention of lawyers. And God knows, Southern Baptists don’t need lawyers to have a conflict. But today we find ourselves in the midst of a significant conflict. And I believe it is a conflict owing DIRECTLY to the exact issues that my motion seeks to address.”

He suggested that the Executive Committee in recent years has received “questionable legal advice” from its attorneys, especially Guenther, Jordan and Price.

“The Southern Baptist Convention is now in a moment of crisis,” he testified before the subcommittee. “A conflict of unprecedented scale and potentially irrecoverable polity disintegration has gripped our convention.”

He told of sitting in the Executive Committee session the day before, “completely stunned” as he listened to one trustee “publicly state that the committee is not duty-bound to adhere to the will of the messengers who elected them. This is not the way I have known Southern Baptist polity and governance to work.”

“To learn that this line of legal argument, which appears to be a perversion of our historic system of trustee governance, is being proffered by the same lawyers who are paid by the Cooperative Program is disconcerting at best.”

“To learn that this line of legal argument, which appears to be a perversion of our historic system of trustee governance, is being proffered by the same lawyers who are paid by the Cooperative Program is disconcerting at best. That the convention is paying lawyers to advise an entity we own to dismiss the clear and legal action taken by our convention messengers is unconscionable.”

After Adkins sat down, he said, the Executive Committee’s vice president, Greg Addison, announced that the committee already had hired yet another law firm from Arkansas to advise on the Adkins motion.

“Upon hearing the engagement of a third firm, a few of the committee members appeared concerned,” Adkins reported. “Keep in mind that just the day before there had been quite a ruckus in the general sessions (and from what I understand, in executive session as well) regarding the influence of the lawyers in this deliberative process.”

Now that the landscape suddenly has changed, with the resignation of Guenther, Jordan and Price, there is more hope that his concerns will be taken seriously, Adkins said. “I am now hopeful such a course correction might be realized. Let’s get this fixed ASAP.”

Long history with the SBC

Across more than six decades of legal counsel to the SBC, this is not the first time Jim Guenther and his firm have become lightning rods amid denominational controversy. Guenther’s guidance during the late 1980s and early 1990s — as the final throes of the “conservative resurgence” were playing out in control of SBC entities — also stirred comment, sometimes from the conservatives and sometimes from the moderates.

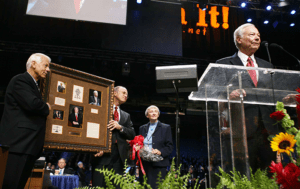

Jim Guenther was honored for his service to the Southern Baptist Convention in 2006. Shown with him at that year’s annual meeting are, from left, former SBC President Bobby Welch; Augie Boto, formerly of the SBC Executive Committee staff; and Guenther’s late wife, Patsy Guenther. (Photo courtesy of the Southern Baptist Convention Historical Library and Archives)

In 1988, when a newfound conservative majority on the Executive Committee attempted to defund the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs (today known as BJC), Guenther advised they couldn’t do it because convention messengers just three months earlier had adopted a budget that specifically allocated funding to the religious liberty group. The Executive Committee, he said, cannot override an action taken by the SBC in annual session.

“The Executive Committee only has the authority to disburse the funds as the convention allocated them,” he said at the time. “The Executive Committee must recognize the sovereignty of the SBC.”

Two years later, in July 1990, SBC moderates who were outraged at the Executive Committee’s firing of Baptist Press editors Al Shackleford and Dan Martin criticized Guenther for what they believed was his empowerment of that decision. The most visible sign of that was a published report the next day that Guenther had been involved in hiring armed off-duty Nashville police officers to guard Executive Committee members while they met in closed session to fire the two editors.

As the SBC leadership shifted dramatically from when Guenther began serving the convention in 1966 to the present — marred by the departure of moderates to form alternative bodies — Guenther and his firm continued to find favorable employment with whoever was in charge. And to partisans on both sides that was an odd reality.

What lies ahead by way of legal counsel to the Executive Committee and the convention itself is anything but clear. Part of that decision will be determined by whether Executive Committee President Ronnie Floyd and his top staff members survive the after-effects of this summer’s duress and the coming storm of an independent report on handling of sexual abuse cases.

Related articles:

What’s old is new again: Conservatives threaten funding over SBC’s ethics agency | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

Who are the key players behind the SBC Executive Committee’s response to a sexual abuse investigation? | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

SBC Sexual Abuse Task Force has lost one-third of its time to delays, but now the work may begin