How much money should a denominational body have to give to a university in return for the ability to control that university’s governance?

Turns out, not much in many cases.

As state, regional and national denominational bodies have faced declining incomes, their affiliated universities have faced dramatically increasing costs. Lower annual contributions from the denominations, combined with growing overall revenue needs for higher education have created a paradox: In many cases today, denominational groups that control electing university trustees provide 1% or less of a university’s revenue.

In some cases, the denominational bodies control 100% of a university’s trustee nominations while providing a minute fraction of the annual revenue.

In some cases, the denominational bodies control 100% of a university’s trustee nominations while providing a minute fraction of the annual revenue. This has led to major philosophical disputes between universities and their alumni, between universities and their denominations and between universities and their larger donors.

But there are reasons some universities haven’t cut ties with their denominational bodies. These include historical identity, student recruitment, pressure from the denominations, and the reality that even a $1 million annual contribution would require a $20 million endowment to replace.

While this dilemma is especially prominent among Baptist universities, it also looms large over Lutheran and Methodist schools, as well as among other denominational traditions. One of the outliers to the issue is the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., which has a completely decentralized system of schools.

How did we get here?

Among Baptists — and a similar story may be told for other denominational groups — creating institutions of higher education became a priority in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of the denominationally affiliated schools outside the Northeast date to this period, although denominations had been starting colleges in the East for years prior.

Also in the late 19th century, among Baptists, the concept of state Baptist conventions was emerging, creating a broader layer of cooperation than local associations, each of which perhaps encompassed a few counties.

Baylor, 1892

Texas provides a clear example of this historical context. What is today known as Baylor University was the first Baptist college founded in Texas and was intended to be the primary, unified Baptist school in the state. Baylor was formed in 1845 by a group called the Texas Baptist Education Society, which predated creation of the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

In time, however, Baylor solidified its relationship with the new state convention out of financial need. The school received an updated charter in 1886 and soon after, trustee President B.H. Carroll stated: “The Convention was our Pharaoh, and we were the Israelites making bricks without straw.” Those words would prove to be prophetic well into the latter 20th century and beyond.

In his sesquicentennial history of Texas Baptists, Leon McBeth reports that by 1892 Baylor University faced a “staggering debt” of $92,000. A young George W. Truett, who was at the time described as “uncolleged,” stepped in, canvassed the state over 23 months and raised $92,000 to save Baylor.

Around that time, a flood of new Baptist schools popped up in Texas, and most of them soon faced dire financial circumstances due to the financial panic of 1893. By 1898, a new Texas Baptist Educational Commission had formed to bring the Texas Baptist schools together in federation.

Through that education commission, the colleges and universities agreed to let the state convention name their trustees and, in return, the commission agreed to raise funds for all the schools. McBeth reports: “The Education Commission launched an ongoing series of financial campaigns to finance the schools. Most of these were marked by great enthusiasm, handsome pledges, and little actual cash raised.”

Over time, the surviving schools — and several new ones mainly formed between 1900 and 1910 — assumed more direct control of their fundraising but also received some annual funding from the state convention. In most every case, the state convention still held total sway over trustee governance.

Bill Crouch

“My grandfather in the late ’30s early ’40s was director of Training Union for the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina,” recalled Bill Crouch, former president of Georgetown College in Kentucky and now a fundraising consultant. “I remember him saying that these colleges, most of them in very rural areas, were placed there for a reason.”

He remembers seeing an old advertisement for one of the schools that said: “Send your children (here), it’s eight miles from the nearest known sin.”

Affiliation with denominational bodies helped with recruitment of students and trust of parents, he explained. And having a steady source of income also seemed like a fair trade for governance control.

“During the war (World War I) or right after the war, the colleges began to struggle financially. A deal was struck state by state that the conventions would invest in you, but the conventions wanted 100% control of the governance. It was a survival option. It wasn’t forced upon them; it was given to them. The state conventions said, ‘We’ll invest money in you, but we want governance of you,” Crouch said.

Wake Forest breaks away

Within the modern era, Wake Forest University in North Carolina was the first of the Baptist-affiliated schools to break away. In 1986 that break was finalized by vote of the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, which chose to sever what already were loose ties with the highly rated research university.

Old Wake Forest University

By that vote, the state convention released Wake Forest to elect all its own trustees in exchange for receiving no more money from the convention. The year prior, the convention had contributed just $500,000 of the school’s $141 million budget — 0.35% of the annual revenue.

Trouble had been brewing since the 1970s — and in reality since the early 20th century — as the more conservative state convention tangled with the university over academic freedom, the acceptance of government funding and the teaching of evolution. For example, in 1977, the National Science Foundation awarded the university a $300,000 grant, of which $85,000 was to be used to construct a biology department greenhouse. The Baptist convention didn’t like that and asked the university to spend the money some other way. University trustees refused.

The greenhouse dispute was not about science or evolution, as it might appear 50 years after the evolution controversy, but was about bricks and mortar. The state convention did not want its universities to take government money for physical projects.

So by 1986, when the university and state convention fully parted ways, it was the natural outcome of a longstanding problem.

Five other schools affiliated with the Baptist State Convention of North Carolina broke away from convention governance at the same time in 2007. Those schools are Campbell University, Chowan University, Gardner-Webb University, Mars Hill College and Wingate University.

That unanimous break was hastened by a development within the national denomination.

That unanimous break was hastened by a development within the national denomination. It was only after the SBC amended its program assignments to give college-level education to its six seminaries that some of the North Carolina college and university presidents changed their position and asked to be free. Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, an SBC seminary located in North Carolina, had started offering undergraduate programs.

That change in program assignments has played a major role in relationships between state conventions and their schools since now through the SBC’s unified budget, the Cooperative Program, states support the seminary-related colleges as well as their state schools. And in most cases, support for seminary-related colleges is increasing while state convention schools experience decreased support.

A new relationship for Samford

Ironically, the president of the state Baptist convention at the time the five North Carolina schools broke away was Mark Corts, whose brother, Tom Corts, was president of Samford University, a Baptist-affiliated school in Alabama, which 30 years later also would break ties with its state convention, although under a different president.

The Samford break with the Alabama Baptist State Convention was fully realized Jan. 1, 2018, but began 24 years earlier, when the university reverted to its original structure and declared a self-perpetuating board not named by the state convention. The school continued in an affiliated relationship with the convention, though, and still received funding through 2017.

The Samford break with the Alabama Baptist State Convention was fully realized Jan. 1, 2018, but began 24 years earlier, when the university reverted to its original structure and declared a self-perpetuating board not named by the state convention. The school continued in an affiliated relationship with the convention, though, and still received funding through 2017.

The initial trustee decision resulted in two years of negotiations between the state convention and Samford that resulted in an operating agreement that was overwhelmingly approved by the state convention. That agreement included a plan whereby names of trustees were presented to the convention for ratification. Also, the Samford charter stayed the same and it contained the stipulation that all trustees would be active Alabama Baptists. A lawsuit was prepared but never filed because of convention approval of the negotiated agreement.

However, the relationship hit a rocky patch again in 2017, when application was made to form a student group to discuss LGBTQ issues. When the state convention heard about the student group’s application, a State Board of Missions study committee was approved and the first action they took was to send a demand letter saying Samford must not allow the proposed group or the convention would withdraw its funding.

Subsequently, Samford’s accreditation was threatened because of the perception that an outside group was exerting undue influence on the governance of the institution.

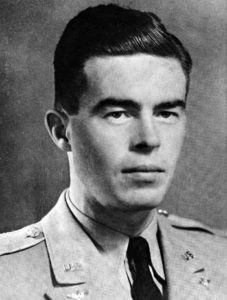

Andrew Westmoreland

Samford President Andrew Westmoreland said the convention’s demand letter threatened the school’s accreditation and led trustees to decline any additional money from the state convention. In return, Samford no longer would submit trustees for ratification and the state convention executive director no longer would sit on the trustee board.

Rather than be controlled by the state convention on this issue, the university forfeited the convention’s $3 million annual contribution toward its $166 million budget, thereby losing 1.8% of its annual revenue stream.

Samford is still listed as a “fostered entity” of the state convention and reports regularly to the convention in annual sessions and in associational meetings.

Baylor sends up a flare

After Wake Forest, the next big chapter in this story begins with “the controversy” in Southern Baptist Convention life, when two men figured out a way to gain control of the SBC’s boards and institutions by controlling the convention presidency beginning in 1979. Soon, fear rippled into more independently minded state conventions, like Texas, that these new powerbrokers would next take over the state conventions — which they, in time, in fact did. Even though, legally, the state conventions are fully autonomous from the SBC.

Fast forward to Sept. 21, 1990. On that day, with no advance notice, Baylor University’s board of trustees — all elected to their posts by the Baptist state convention — adopted an amended charter that created a new self-perpetuating board of regents no longer controlled by the state convention, as had been the case since 1886.

Herbert Reynolds at this Baylor inauguration, 1981.

Baylor President Herbert Reynolds said afterward that the action was necessary to protect Baylor from the encroaching fundamentalism of the SBC, which trustees feared was on its way to Waco in rapid order.

The university trustees did their homework and concluded that this was possible since the university had been chartered under the Republic of Texas, predated the state Baptist convention, was created by a Baptist Education society that no longer existed and — most importantly — the university’s 1845 charter never had been amended to remove a provision that the trustees themselves had the sole legal authority to amend the charter. Even though the state convention’s constitution claimed for it the right to approve all charter changes for its institutions, the Baylor charter predated that and was found to supersede it.

After two years of negotiations, Baylor and the BGCT agreed to a process in effect still today whereby the university names 75% of the board and then works through the BGCT to elect the remaining 25%.

This change was a shockwave heard around the nation and eventually set off a wave of Baptist schools in other states separating from or loosening ties with their state Baptist conventions.

Among those: Mercer University in Georgia, Belmont University in Tennessee, Samford University in Alabama, Georgetown College in Kentucky, William-Jewell College in Missouri, Furman University in South Carolina, Stetson University in Florida. Later defections from state convention ties included University of the Cumberlands and Campbellsville College, both in Kentucky.

A student-initiated revolt in Missouri

The Hilltop Monitor, student newspaper of William-Jewell College, in 2015 published a retrospective on the school’s split with the Missouri Baptist Convention. The action began in February 2003 when the Student Senate amended the Student Bill of Rights to include sexual orientation as a focus of disallowed discrimination.

David Sallee, president at William Jewell at the time the 2015 article was written, told the paper: “Jewell was founded by Missouri Baptists in 1849. During that period of time, Missouri Baptists established 12 to 15 colleges around the state, many of which did not survive for very long. We were founded by Missouri Baptists, but we were established through an act of the Missouri Legislature, meaning that the legislature wrote a specific law establishing William Jewell, as opposed to us just being established under the other laws of the state.”

David Sallee, president at William Jewell at the time the 2015 article was written, told the paper: “Jewell was founded by Missouri Baptists in 1849. During that period of time, Missouri Baptists established 12 to 15 colleges around the state, many of which did not survive for very long. We were founded by Missouri Baptists, but we were established through an act of the Missouri Legislature, meaning that the legislature wrote a specific law establishing William Jewell, as opposed to us just being established under the other laws of the state.”

Among those rights, Sallee said: autonomous governance

The Missouri Legislature “allowed for a self-perpetuating board of trustees, which is very important,” he explained. “Self-perpetuating means the board elects its own members, as opposed to an outside group electing the members. So most Baptist colleges, their members are elected by a state convention, but that was not true for the founding of the college.”

Exercising that right, however, meant breaking ties with the state convention.

What started in the Student Senate soon became an issue with the college’s trustees — not in restricting the student government leaders but in resisting pressure from the state convention to do just that.

State convention officials put pressure on the college to intervene in the Student Senate’s decision about the Student Bill of Rights. Initially, college trustees decided to “wait it out” and see what action the convention would take. Nine months later, the convention took its own action to cut ties with the college.

This all played out just months after the state convention filed its lawsuit against five other affiliated institutions that attempted to break away on their own.

This all played out just months after the state convention filed its lawsuit against five other affiliated institutions that attempted to break away on their own. One question raised by messengers at that year’s annual meeting of the state convention was why it was bad for the five institutions being sued to elect their own trustees since Jewell already did. That put the convention leaders in an awkward position of supporting a school that elected its own trustees and was perceived to be more liberal than the other institutions.

Some observers believe the relationship between the Missouri Baptist Convention and Jewell would have ended that year no matter what because the state leaders were looking for a reason; the Student Bill of Rights just became a convenient issue.

Whatever the reason, the split meant William Jewell lost about $1 million in annual funding from the state convention but gained the ability to set its own trustee demographics and student life policies.

Under convention control, Jewell was required to have half its trustees be Baptists and one-third specifically Baptist pastors. Also, half the entire faculty was required to be Baptist. The state convention never directly named trustees but chose from names submitted by the university for consideration.

Ironically, the Student Bill of Rights issue — that the state convention attempted to stop — lost in a campus-wide student vote.

Nevertheless, after the split, the college adopted student life policies more consistent with non-Baptist schools: Student of legal drinking age were allowed to consume alcohol on campus, dorms became co-ed and a gay and lesbian support group was created. Sallee summarized to the student paper: “We, in general, have become less parental when it comes to student life.”

A story told over and over but with some twists

Similar stories can be told of other Baptist schools that broke ties with their state Baptist conventions. Some have maintained cordial relationships with the state conventions afterward, and some have not. Each story has its own twist, but the common thread always returns to demands for control that are not matched by cash in the coffers.

In a few cases, schools have thought that they — like Baylor — had authority to make unilateral decisions but later learned they did not have similar authority and had to reverse course. Two legal cases in two states illustrate this.

In Georgia, Shorter College after years of a contentious relationship with the Georgia Baptist Convention declared a self-perpetuating board of trustees, removing the state convention from its governance. From 1959 to 2001, the state convention chose college trustees from a larger list of candidates provided by the school. By 2002, the state convention began unilaterally naming trustees without consulting Shorter’s leadership.

In Georgia, Shorter College after years of a contentious relationship with the Georgia Baptist Convention declared a self-perpetuating board of trustees, removing the state convention from its governance. From 1959 to 2001, the state convention chose college trustees from a larger list of candidates provided by the school. By 2002, the state convention began unilaterally naming trustees without consulting Shorter’s leadership.

The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools began warning that the state convention had too much control over Shorter’s governance and its accreditation was at risk. That led college trustees to vote to sever ties with the Georgia Baptist Convention and to take the convention to court to continue getting donations it received for Shorter.

This court drama finally reached the Georgia Supreme Court where, in 2005, the trustees lost by a single vote. Judges decided Shorter’s board did not have the authority to break ties with the convention.

Within six years of the state convention gaining absolute control of the trustee board at Shorter, faculty and staff were required to submit to both a doctrinal test for employment and agree to a “lifestyle” statement. As a result, 83 of Shorter’s faculty, staff and administration resigned over the next year, including 35 of its 94 full-time faculty members on the undergraduate campus. The college lost four of its deans and a vice president.

In Missouri, a court also overturned the attempt by Missouri Baptist University to declare a self-perpetuating board — although it took 17 years of litigation. The university was one of five Missouri Baptist entities to face litigation after declaring independence from the state convention in 2000 and 2001. Two of those were successful in the breakup, but three were not.

In Missouri, a court also overturned the attempt by Missouri Baptist University to declare a self-perpetuating board — although it took 17 years of litigation. The university was one of five Missouri Baptist entities to face litigation after declaring independence from the state convention in 2000 and 2001. Two of those were successful in the breakup, but three were not.

As a result of the February 2019 court ruling, the entire board of trustees for Missouri Baptist University was replaced with a slate named by the state convention.

In Kentucky, a delayed reaction

When Bill Crouch arrived at Georgetown College in Kentucky as president in 1991, his trustees had to be Baptist, had to live in Kentucky, had to go to church two out of four Sundays a month, and had to be approved by the Kentucky Baptist Convention.

“I had three Fortune 500 CEOs who were alums of mine who couldn’t be trustees,” he explained. But on the other hand, the state convention swung a big carrot in return for those restrictions: “We were getting $3 million a year from the KBC. That is the equivalent of a $46 million endowment.”

Early photo of Georgetown College Library.

At the time KBC gifts represented about 6% of total revenue for the college, but over time the ratio shifted. “It was probably closer to 3% by 2002,” he said.

In those days in Kentucky — before the state convention was taken over by the fundamentalist movement in the SBC — relations between the three KBC-affiliated university presidents and the convention were cordial. The state convention nominating committee worked closely with the presidents on trustee nominations — within the defined bounds, but still respecting the wishes of the presidents to bring on donors and alumni and people with expertise in higher education.

Ironically, the Georgetown trustees knew when they hired Crouch that his father and grandfather had been involved with Wake Forest University leaving the North Carolina Baptist Convention.

“One of my instructions the first year was to create a plan where we might leave the KBC if it were to the point where we were going to lose our academic freedom. We were able to hold off another 13 to 14 years.”

Finally, by 2006, Georgetown College broke with the state convention. “We were fortunate, we never got sued,” he said. “A lot of other schools got sued. By 97% approval we were able to leave the convention and they funded us four more years” in a step-down formula.

Still, it was hard. “The college was so dependent on that unrestricted money because tuitions were rising out the roof and facilities were needing repairs, and there was all this divide within the Baptists.”

At the time, the Lexington Herald-Leader reported that Georgetown College was receiving $1.3 million a year from the KBC, about 3% of its operating budget.

A historical precedent in Georgia

William Jewell College and Georgetown College, like most faith-based schools, are liberal arts colleges. These two schools relied more heavily on denominational funding than the comprehensive universities that shed denominational control. For larger schools, breaking away is easier because they have many more resources and larger alumni bases.

Kirby Godsey on the cover of Macon Magazine.

That’s certainly the case for Mercer University, which not only has deep historical ties in Georgia — akin to Baylor’s story in Texas — but is a larger, more prominent school than other schools in Georgia. If Baylor were considered the crown jewel of Baptist higher education in Texas — a phrase actually used in the early 20th century — Mercer would have been the crown jewel of Baptist higher education in Georgia.

Mercer was founded in 1833 by Georgia Baptists and is the oldest private university in Georgia. When the school broke ties with the Georgia Baptist Convention in 2006, it ended a 173-year relationship.

But that break actually happened in stages and predates the late-20th century conflict in the SBC.

This story begins in 1939 when Mercer had a famous heresy trial on campus. John Birch — yes, that John Birch, namesake of the far-right John Birch Society — as a Mercer senior that year joined a group of 12 other students in accusing four professors and a student laboratory assistant of heresy.

John Birch

Their primary focus was on Professor John D. Freeman, who taught in the Christianity department.

Kirby Godsey, president of Mercer from 1979 to 2006, tells the story: “The trustees held a heresy trial all day long in Groover Hall. Trustees found Professor Freeman innocent of those charges, but it really broke his heart. To be attacked like that was something he couldn’t bear. After that, the trustees were obviously in conflict with the convention … so a committee of convention people and trustees came together in a small group of about half a dozen, and they reached an agreement about the makeup of Mercer’s board.”

Thus in 1939 — bucking the trend everywhere else of increasing denominational control — Mercer gained the ability to indirectly determine its own board of trustees while still receiving funding from the Georgia Baptist Convention.

What that meant for Godsey when he became president 40 years later — the very year the fundamentalist takeover effort in the SBC began — was this: “While the convention would elect our trustees, they could do so only from persons nominated by the board at Mercer. They couldn’t just put somebody on our board. We interpreted that pretty generously while I was there. We set up the system that we would provide three nominees for each vacancy. We had a big board, 45. … We just told them you can choose one of these three or reject all them and we’ll give another set.”

Godsey worked this process for 27 years. “I would go to these meetings and the other colleges were there, and (the Georgia Baptist Convention) just put whoever they wanted on these college boards, friends and preachers and people who had the same ideology they had. … Eventually it became thoroughly fundamentalist. They would often ignore what the presidents wanted.

Godsey worked this process for 27 years. “I would go to these meetings and the other colleges were there, and (the Georgia Baptist Convention) just put whoever they wanted on these college boards, friends and preachers and people who had the same ideology they had. … Eventually it became thoroughly fundamentalist. They would often ignore what the presidents wanted.

“In our case,” Godsey said, “when I went in, for the first 30 minutes I had to sit there and listen to that committee harangue and complain about our methodology. … I would listen to that and at the end — I never argued with the fundamentalists —I’d say, ‘Thank you for your comments; I’m here to present you a slate of trustees.’”

This gave Godsey all sorts of freedom his counterparts at other Baptist schools didn’t have. “We did not require that trustees be Baptists,” he noted. “I wanted a Roman Catholic on the board. I didn’t put a Baptist in the group (for the committee to choose from), so they couldn’t choose a Baptist.”

As the battle for the SBC and its affiliated state conventions raged, Mercer maintained a non-fundamentalist board of trustees. “This was an academic institution,” Godsey said. “We couldn’t be ruled by the whims of the convention.”

The ascendant conservatives in Baptist life came to loathe not only Mercer’s escape from their control but Godsey individually.

In 1996, Smyth & Helwys, then a new moderate Baptist publishing house based in Macon, published Godsey’s book When We Talk About God … Let’s Be Honest. That book set off a firestorm of protest and led some Georgia pastors to accuse Godsey of heresy.

Among Godsey’s critics was a young Al Mohler, who had just left the editorship of Georgia Baptists’ newspaper, the Christian Index, to become president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky.

At the time of this controversy, Mohler told Baptist Press: “The word heresy has been considered off-limits for too long. Those who love the truth must oppose error.” He accused Godsey of “theological error” that goes to “the very heart of the gospel.”

This book “drove them crazy,” Godsey recalled. “They called for me to be fired.”

Eventually, the executive director of the Georgia Baptist Convention, Robert White, was invited to speak to the university’s board of trustees about the concerns. He made his case, then sat down, and the chair of the board asked if there were any questions.

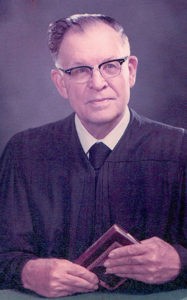

Judge Bootle

Present in the room was Judge William Augustus Bootle, a life trustee of the university, which meant he had the power to speak to the board but no longer could vote. Bootle, then in his 90s, had been a young leader at Mercer back in 1939 and had been instrumental in framing the governance compromise that kept Mercer affiliated with the Georgia Baptist Convention after the debacle of the John Birch-inspired heresy trial.

Godsey watched the scene play out: “Judge Bootle sat in silence for a few minutes, then stood up at his little desk and said, ‘Mr. Chairman, if the president is not free, no one in the university is free.’ And then he sat down, and that was the end of it. There was no other discussion.”

Still, Mercer maintained its connection with the Georgia Baptist Convention for another decade. Finally, by 2005, the relationship was too strained to continue. Godsey approached the board with a recommendation that it break ties with the state convention.

“I said our differences had become so significant and substantial that we’d be better to separate from the convention and enjoy hopefully a fraternal relationship,” he recalled. “We as a university should be independent. The trustees voted unanimously to withdraw.”

That was December 2005. At the time, the Georgia Baptist Convention gave Mercer about $3 million a year in undesignated revenue. “It was 2% or 3% of our revenue,” Godsey recalled. “The cost of that money was too great. There was a continuing effort to interfere in our operations.

“The university simply could not be managed by a political constituency of a Baptist convention.”

“What I wanted to do was to protect the academic integrity of the university. We’re built on intellectual freedom, on religious freedom and respect for religious diversity. That became my mantra. The university simply could not be managed by a political constituency of a Baptist convention.”

Two current applications

What Mercer faced and what Baylor sought to avoid currently have two other Baptist schools embroiled in controversies about denominational governance given for scant funding.

Chief among those is Southwest Baptist University in Bolivar, Mo., which is affiliated with and controlled by the Missouri Baptist Convention. The battle for control of the SBC that began in 1979 has taken full root in Missouri, where SBC-style fundamentalists now control the state convention. Some schools, like William Jewell, have gone their own way. But Southwest Baptist University remains.

Even though it is considered a conservative school by any outside definition, leaders of the state convention and critics among Missouri Baptist pastors have found the school to be not conservative enough. They recently required religion faculty, for example, to affirm four separate doctrinal statements, including the 2000 Baptist Faith & Message doctrinal statement of the SBC.

Even though it is considered a conservative school by any outside definition, leaders of the state convention and critics among Missouri Baptist pastors have found the school to be not conservative enough. They recently required religion faculty, for example, to affirm four separate doctrinal statements, including the 2000 Baptist Faith & Message doctrinal statement of the SBC.

The conflict over control of the university — and its governing board — escalated this fall with the abrupt resignation of President Eric Turner.

In October 2019, the Missouri Baptist Convention replaced the university’s entire slate of trustees to put five new trustees on the board. In his report to the convention’s annual meeting, Turner criticized that action, which deviated from a previous pattern of collaborative board nominations. This year, the convention officially amended its Nominating Committee rules to align with its actions last year and give more absolute authority in trustee selection to the convention.

Alumni and other defenders of the university point out that the state convention provides less than 2% of the university’s annual revenue. For less than 2% commitment to funding, the Baptist convention retains 100% control over trustee selection and thereby governance.

As with so many Baptist colleges and universities, it didn’t start out that way. Southwest Baptist University, founded in 1878, was chartered by the state of Missouri. Facing financial difficulties, the school in 1921 deepened its ties with the state convention, which brought in more funding and more control. That same year, the school gained accreditation after struggling for decades and even closing completely from 1910 to 1913 before relaunching.

As with so many Baptist colleges and universities, it didn’t start out that way. Southwest Baptist University, founded in 1878, was chartered by the state of Missouri. Facing financial difficulties, the school in 1921 deepened its ties with the state convention, which brought in more funding and more control. That same year, the school gained accreditation after struggling for decades and even closing completely from 1910 to 1913 before relaunching.

The political situation among Missouri Baptists has been so fraught that the convention ended up in more than 16 years of litigation with five formerly affiliated institutions the convention sought to retain control over. Among those five was one other university, although Southwest Baptist was not in the group.

In 2003, about five months into the legal fight, Baptist layman and attorney Darrell Moore proposed that all sides drop litigation and agree that the convention would get to elect the percentage of trustees that matched the percentage of revenue the convention gave each institution. That would have meant less than 50% control over the five institutions being sued and less than 20% for some in particular.

The state convention rejected that. It wanted 100% control despite giving only a fraction of each institution’s revenue.

Back to Texas

Similar concerns about governance control for relatively little funding have surfaced in a current dispute at Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, Texas. The school’s president and trustees have come under fire from an ad hoc alumni group for a decision to close the university’s Logsdon Seminary.

University leadership claims the closure was necessary to correct a dismal financial strain. The alumni group — called Save Hardin-Simmons — claims the administration has misrepresented the financial situation and has wrongly used investments intended for the seminary to keep the rest of the university afloat.

University leadership claims the closure was necessary to correct a dismal financial strain. The alumni group — called Save Hardin-Simmons — claims the administration has misrepresented the financial situation and has wrongly used investments intended for the seminary to keep the rest of the university afloat.

Save Hardin-Simmons also charges that the university administration has been unduly influenced and threatened by a few conservative West Texas pastors who thought the seminary was too liberal. University administrators deny this charge while acknowledging there are different visions of where the school should fall on certain issues of the day.

The university’s trustees are required to “maintain membership in a Baptist church” during their terms of service, according to the school’s website. A controlling majority (51%) of the board is chosen by the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

“The root of the problem in the case of Hardin-Simmons is that BGCT names 51% of university trustees while giving only 0.7% of the annual budget. This is not only the case at HSU, but many other similar institutions,” said Jonathan Davis, an alumnus and leader of Save Hardin-Simmons. “Giving the BGCT a level of influence that is disproportionate to its own financial support arguably and needlessly causes erosion of academic freedom.”

Like so many other Baptist colleges and universities, the relationship between Hardin-Simmons and the state convention has changed over time. The school was founded as Simmons College in 1891 by the Sweetwater Baptist Association — which then encompassed a vast swath of West Texas — and a group of cattlemen and pastors. It was the first school of higher education established in Texas west of Fort Worth.

Like so many other Baptist colleges and universities, the relationship between Hardin-Simmons and the state convention has changed over time. The school was founded as Simmons College in 1891 by the Sweetwater Baptist Association — which then encompassed a vast swath of West Texas — and a group of cattlemen and pastors. It was the first school of higher education established in Texas west of Fort Worth.

The West Texas school was founded to be distinctly Baptist but to follow “the Roger Williams doctrine of entire liberty in religious concernment” and that “no religious test shall ever hinder any person … from entering and receiving instruction,” McBeth reports.

Unlike most other Baptist schools of the time, Simmons College began without debt, thanks to generous benefactors. And when in 1898 the other Texas Baptist school joined the new “federation of schools” proposed by the Texas Baptist Education Commission, Simmons College declined. It was not until 1941 — 50 years after the school’s founding — that it became formally affiliated with the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

A high price for Belmont

Among all the Baptist schools that have broken away from governance control by state Baptist conventions, none has paid a higher price to do so than Belmont University in Nashville.

The school, which today has deep ties to the music industry, voted to create a self-perpetuating board in 2005. Even though the university proposed to maintain a “fraternal relationship” with the Tennessee Baptist Convention and require all board members to be Christians including 60% who would be Baptists and grant the head of the state convention an ex officio seat on the board, the convention said no and filed suit against the school, seeking $58 million in damages.

The school, which today has deep ties to the music industry, voted to create a self-perpetuating board in 2005. Even though the university proposed to maintain a “fraternal relationship” with the Tennessee Baptist Convention and require all board members to be Christians including 60% who would be Baptists and grant the head of the state convention an ex officio seat on the board, the convention said no and filed suit against the school, seeking $58 million in damages.

After two years of litigation, Belmont agreed in 2007 to pay the state convention $11 million over 40 years.

A news release from the school at the time said $1 million was to be paid in 2008 and the university would make annual payments of $250,000 to the convention for the next 40 years. The university statement explained: “These gifts are an expression of gratitude to Tennessee Baptists for the financial and spiritual support that they have provided to the University over the past five decades. The funds will be added to an endowment at the Tennessee Baptist Foundation to support Tennessee Baptist missions and ministries.”

Beyond the Baptist world

These challenges are not unique to Baptists. Lutherans and Methodists, for example, face similar issues.

Michael Dorner

Six years ago, Michael Dorner wrote his doctoral dissertation on the subject. The dissertation’s title: “The Governance of Denominational Colleges and Universities in an Era of Declining Denominational Identity among Students.”

Today, he serves as vice president for finance and assistant professor of accounting at Concordia St. Paul University in Minnesota. The school is affiliated with the Lutheran Church — Missouri Synod.

Within this branch of Lutheranism, the Concordia system encompasses all the affiliated colleges and universities. There used to be nine schools in the system; now there are seven. One school closed this year due to debt, and two merged.

Currently, all trustees of schools within the Concordia system must be members of Missouri Synod Lutheran churches. They are elected in a blended approach, however, that gives half the nominations to the denomination and half to the institution itself. For every four trustees elected, one is to be a pastor, one is to be a teacher and two are to be laypersons.

In the past, say 70 years ago, these boards were more likely to be called boards of control, he explained. “The nature of serving on the boards has changed a lot. Seventy years ago, it was more a matter of overseeing what is being taught.”

At that time, the Lutheran churches were concerned with trustees maintaining reine lehre, German for “pure teaching,” he said. Today, trustees deal with more practical matters and not just doctrinal purity.

“You have these conventions making decisions about how these institutions are supposed to operate, and what do they know about higher education?”

Higher education is an extremely complex enterprise in today’s world, he added. “You have these conventions making decisions about how these institutions are supposed to operate, and what do they know about higher education?”

Financially, Missouri Synod Lutherans — like Baptists — used to give more money to their schools than they do today. “Thirty years ago, we might have been getting about 20% of our revenue,” Dorner said. “By 2005, that was down to zero. We haven’t received any operating funds. They have some endowments they hold that they (the denomination) distribute for student scholarships.”

The Methodist landscape

Scott Miller serves as president of Virginia Wesleyan University and leads the North American Association of Methodist Schools, Colleges and Universities. That group brings together colleges and universities with historic relationships to the United Methodist Church, whether currently affiliated with the church or not.

Scott Miller

He’s a lifelong Methodist and has served a combined 30 years in four presidencies of schools affiliated with the UMC.

Due to conflict within the Methodist church — particularly over LGBTQ inclusion — some Methodist schools have dropped affiliation with the denomination.

“The Methodist colleges have affirmed for years that we are inclusive, that we don’t discriminate,” Miller explained. “Several times the Methodist presidents as a whole have asked the Council of Bishops … to clearly make some statements and take a different perspective on LGBTQ rights. We don’t think our sponsoring organization accurately reflects the institutions of higher education.”

This tug-of-war “finally came to a head four or five years ago,” he said. “A number of institutions said, ‘The bottom line is we don’t share the perspective of the church on LGBTQ issues. Students will not go to institutions that are part of an organization that appears to discriminate.”

The association he leads — called NAAMSCU for short — seeks to keep all the historically Methodist schools working together, despite whatever the denomination does.

There were 117 institutions classified as Methodist schools serving K-2 through seminary. That number is down to closer to 100 now, and 15 to 20 of the remaining schools “have hit the pause button” on decisions, Miller said, pending the outcome of the already delayed UMC General Conference.

“A number of institutions are just saying … we don’t want to abandon our founding denomination but at the same time we don’t want to (be bound by) discrimination,” he said.

NAAMSCU itself is working to become free of denominational support. It currently is considered part of the UMC’s General Board of Higher Education. “It is our hope in the next six or eight months that NAAMSCU will become independent from the church — meaning we would have a relationship but that our governance would be independent.”

Being an affiliated institution with the UMC is a complicated process that requires a study and review every 10 years. Virginia Wesleyan most recently went through this reaffirmation process in 2016.

In return, the school initially received about $168,000 of unrestricted money from the denomination but this year is getting only $21,000. That’s against a total revenue flow of $46 million needed to run the university — which is 0.00046% of the school’s revenue.

“We all love the group that founded us. … But how much governance influence should the church have at an institution it is not giving financial support?”

“We all love the group that founded us,” Miller said. “We respect and appreciate the role they’ve played in our funding and history. But how much governance influence should the church have at an institution it is not giving financial support?”

One of the requirements of UMC affiliation is for schools to employ a chaplain. Yet many of the schools receive so little denominational funding that it does not even cover the cost of the chaplain’s position.

Often, Methodist schools were founded or have historical ties to district or regional Methodist bodies rather than the UMC itself. And some schools receive financial support from those bodies as well.

“The most I’ve heard that any of our affiliated schools are receiving from the denomination is a little bit more than $1 million a year,” Miller reported.

Unlike so many Baptist schools, most Methodist schools have self-perpetuating boards. In Miller’s case, for example, Virginia Wesleyan is required to have two Methodist clergy on the board plus the bishop and district superintendent. The annual conference of the church votes on trustees, but that is largely a formality, he said. Virginia Wesleyan has maintained a stipulation that 40% of its board must be Methodists.

Methodists and property disputes

Some Methodist colleges have a stipulation from their founding that if the school goes out of business their property reverts to the church. An example is Hiawassee College in Tennessee, which closed abruptly last year and this month its property was sold. The asking price was $8.6 million. That money reportedly went to the church.

SMU campus in Dallas

In Dallas, a legal battle is ongoing since Southern Methodist University late last year changed its articles of incorporation to “make it clear that SMU is solely maintained and controlled by its board of trustees as the ultimate authority for the university,” according to a university statement.

That included deleting language from governing documents that said the school was “forever owned, maintained and controlled by the South Central Jurisdictional Conference of The United Methodist Church.”

The SMU campus is located on 237 acres in one of Dallas’ most expensive neighborhoods.

In response to SMU’s action, the South Central Jurisdictional Conference filed a civil lawsuit in Dallas County.

The jurisdiction claims it is “the founder, owner, controller and manager of SMU.” Its suit called the change to the articles of incorporation “unauthorized” and in “violation of SCJC’s rights and interests in relationship between SMU and SCJC that has existed for more than a century.”

In an echo of the Baylor trustee action from 1990, the Methodist jurisdiction claims SMU’s governing documents give the jurisdiction the right to authorize and approve any amendment before it is made.

Again, these matters are not new to Methodists any more than to Baptists.

For the first 40 years of its existence, Vanderbilt University was “under the auspices of” the Methodist Episcopal Church, South — a denominational body predating the United Methodist Church. Vanderbilt trustees severed ties with the church in June 1914 “as a result of a dispute with the bishops over who would appoint university trustees,” the university website reports.

This the first Historically Black College or University to acquire an institution that is not an HBCU.

Another interesting twist in Methodist higher education happened this summer when Wesley College, a Methodist school in Dover, Del., agreed to merge with Delaware State University, a historically Black university. According to a report in Inside Higher Education, this is the first Historically Black College or University to acquire an institution that is not an HBCU.

Wesley already was a minority-serving institution, with 40% of its students Black, 37% white and 7% Hispanic. Delaware State’s student body is three-fourths Black.

About HBCUs

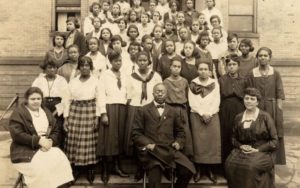

Historically Black Colleges and Universities have followed a somewhat different path. Today, there are 101 public and private HBCUs in the United States, most dating to a period from the abolition of slavery in 1865 to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Like predominantly white institutions, a majority of HBCUs got their start through churches and religious groups.

Samuel C. Tolbert, Jr.

However, the Historically Black Churches in America have not had the same financial resources or accumulated wealth of white denominations in America, noted Samuel Tolbert, president of the National Baptist Convention of America and board chairman at Simmons College of Kentucky, an HBCU in Louisville.

“Even though the denominations were supporting historically Black colleges, they couldn’t compete with other schools. They didn’t have the assets,” he explained.

A recent report on the website Moguldum explained this context. “HBCUs tend not to take in as much in donations as predominantly white schools. Their endowments are on average 70% smaller than those of other schools.”

There are outliers to this situation, however. Howard University, one of the best-known HBCUs in America, has an endowment reported to be $693 million. Howard is a non-sectarian school without denominational ties that has a deep alumni donor base and is able to court donors from all sectors.

That is not the case for the majority of HBCUs, especially the faith-based ones.

Archival photo from Simmons College of Kentucky

Since passage of the Civil Rights Act, the federal government has at times offered special funding for HBCUs. And that cause was a shared point of discussion among most all the contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020. As a candidate, Joe Biden pledged $70 billion in funding for HBCUs as part of a larger plan for strengthening higher education.

Last year, the Trump administration expanded a federal program that loans money for campus improvements to include 40 faith-based HBCUs previously excluded because of church-state separation issues.

Government funding has presented both a help and a problem, Tolbert said. “In the infancy of a lot of these denominationally based HBCUs, there was a dependence on denominations and churches. That’s how they were founded. With increased government funding, there became somewhat of a gap between the historically Black colleges and the historically Black church. In recent times, they’ve had to turn back to the churches because they weren’t getting as much support as they needed.”

Simmons College of Kentucky

One example is Simmons College of Kentucky, which in 2016 created a partnership with the National Baptist Convention of America. That came with a financial commitment from the denomination to the school.

“Our goal now is that 7.9% of our budget would go to Simmons. We voted on it and were unanimous to do it,” Tolbert said. “The challenge has been that COVID hit right after we left that meeting, and we’ve only been promoting our entire finance plan online. We’ve got to get enough participants from churches and associations to make it work.”

When fully realized, this commitment could move NBCA’s financial contributions to Simmons up from less than 1% of the school’s budget to 6%, Tolbert predicted. “That’s monies that would come directly from a National Baptist Convention account. It does not take into account monies that would come from churches and individuals.”

Taken together, individual contributions and denominational contributions will have a “significant impact” on the school’s funding, he said.

NBCA has eight slots on Simmons’ 26-member board of trustees.

Tolbert sees his personal relationship with Simmons and his denomination’s relationship with the HBCU as an incentive to raise support for the school. “That really puts some pressure on me and the convention to be financially supportive of this school.”

Another way for Presbyterians

Among mainline Protestant churches, the Presbyterian Church in America has one of the loosest affiliations with its colleges and universities.

Jeff Arnold

Jeff Arnold serves as executive director of the Association of Presbyterian Colleges and Universities, a voluntary partnership of 54 schools with historic ties to the PCUSA.

“Within the Presbyterian world, we have, depending on who you’re counting, 68 schools that were founded by various entities of the church. About a dozen of those no longer want to affiliate with the church. The national church has never had any governance over any of these schools nor any funding.”

All Presbyterian schools — including the likes of Princeton — were “founded at the local level,” he explained. “They have survived throughout history by the input from those areas. In some areas of the country where presbyteries have endowments, there is more involvement. … The vast majority will sink or swim on their own.”

The denomination, and especially its foundation, does maintain endowed scholarship funds for schools, for both undergraduates and seminarians.

Few of the schools have governing relationships with denominational bodies, he added. “In almost every case, there are no requirements of faculty or trustees.”

Princeton, the original flagship school for Presbyterians in America, ceased formal ties with the church in the 1920s. Its most significant church identification today is through Princeton Seminary.

The website for the seminary explains: “Affiliated from the beginning with the Presbyterian Church and the wider Reformed tradition, Princeton Theological Seminary is a denominational school with an ecumenical, interdenominational, and worldwide constituency.”

Student recruitment challenges

In the modern world, almost as important as funding to colleges and universities is student recruitment. Empty classrooms and dormitories do not pay for themselves.

Historically, denominationally affiliated schools benefitted from a ready supply of prospective students from the churches within their denominations. For many years, for example, Baptists would have been the majority among Baylor and Mercer’s student bodies. That no longer is true. One indicator of this shift is that the Baylor Catholic Blog reported in fall 2019 that 16% of the student body now is Catholic and that Catholics are the fastest-growing segment of the student body.

Yet maintaining denominational affiliation remains important in marketing schools to prospective students and their parents.

“Within the last decade, we’ve seen what I call the Liberty Effect,” said Crouch, the former Georgetown College president. Liberty University, founded by Jerry Falwell and his Thomas Road Baptist Church in Lynchburg, Va., has become one of the largest Christian universities in America.

“They were no longer a Baptist college, they were a Christian college.”

“They were no longer a Baptist college, they were a Christian college,” Crouch explained. “If you love Jesus, come here.”

This Liberty Effect gave modern iteration to a phenomenon of the early 20th century with the rise of nondenominational schools such as Moody Bible Institute, Wheaton College, Bob Jones University and Biola University. All these schools sought to undercut denominational schools. Liberty’s novelty was its leveraging of online education.

Baptist schools have struggled and continue to struggle with the pros and cons of being “Baptist” schools, Crouch said. “I don’t think there was ever a trustee meeting in my 20 years at Georgetown College where there wasn’t a discussion about whether being Baptist helps or hurt us. It was always on the table in conversations.”

Baptist historian and professor Bill Leonard agrees this is a major issue for denominationally affiliated schools. He cites “declining Baptist networks” as a concern.

“The old church, college, seminary networks are significantly impacted by the rise of the ‘nones’ and the distancing of families from church and church related networks, especially schools,” he said. “Add to that the demographic declines, particularly among white families, and you have a demographic reality that schools across the geographic, theological and historical map are experiencing.”

Samford University cornerstone laying when the school moved to its suburban Birmingham, Ala., location in 1957.

On top of that, schools face a daunting demographic reality, Crouch added. “Over the next 10 years, there’s going to be fewer college students coming in. Baby Boomers had babies and sent them to college, but now the population of college-age students is declining.”

Add to that the coronavirus pandemic, which has upended everything about higher education and advanced online learning, and a push for the incoming Biden administration to advance making community college free nationwide.

In his current work as a fundraising consultant, Crouch interacts with many denominational groups, and he finds a consistent trend on these enrollment issues. Like the Liberty Effect, he sees a changing perspective among Methodist schools. “They talk not so much about being a Methodist school as a faith-based institution.”

The simple reality, he noted, is that “denominational connections are not nearly as strong or as important as before. The critics always say it’s a slippery slope to become completely secular. I haven’t seen that. I have seen these schools maintain that their faith base is very important in distinction from the secular universities. A lot of families want their kids to go to places that have chapel.”

Again, this is true beyond the Baptist world.

Dorner, the Lutheran administrator, explained denominations “began to peak in membership around 1970. At the same time most of the universities have continued to grow. They’ve grown in enrollment, grown in programs. Most people would look at them being rather successful. But they attract far fewer students from the denomination than ever.”

And that brings the conversation back to money.

“Students today have much higher expectations,” Dorner said. “There’s been a bit of a facilities arms race among schools.”

That also translates to a question of location, added Miller, the Methodist leader.

“Most Methodist institutions were located in rural areas, the idea being there was no internet, no television, and when churches were founded in rural areas, you wanted small residential campuses where there would be little distractions,” he said. “What’s happened down through the years … is that a major drawback is students today expect there to be a gas station, a restaurant, a bar, … and students don’t want to go to schools in rural isolated areas. Part of the decline is caused by what students are looking for.”

This all works together to feed the crisis related to funding and governance, he added. “A combination of less money, fewer presidents who are members of the denomination, the rural location, lead to challenges that cause the institutions to look more independent.”

Lessons from Grand Canyon

Faced with the kind of financial and student recruitment crisis that has been common to many smaller faith-based colleges and universities, an Arizona Baptist school took an entirely different approach.

Grand Canyon College, founded in 1949 by the Arizona Southern Baptist Convention, became Grand Canyon University in 1984. At the same time, the Phoenix-based school moved from being governed by the state Baptist convention to being self-owned by the board of trustees. The state convention continued to elect university trustees until 2000.

Grand Canyon College, founded in 1949 by the Arizona Southern Baptist Convention, became Grand Canyon University in 1984. At the same time, the Phoenix-based school moved from being governed by the state Baptist convention to being self-owned by the board of trustees. The state convention continued to elect university trustees until 2000.

During this same period, the Arizona Baptist Foundation was embroiled in a scandal that became the largest collapse of a religious financial institution in U.S. history. University trustees sought to steer clear of association with that problem, which reportedly informed some of their decisions.

Still, the university struggled financially and faced the possibility of bankruptcy.

That led to a novel approach in 2004, when the university’s trustees sold the school to a for-profit company, California-based Significant Education. This made Grand Canyon the first for-profit Christian college in the United States. It also became the first for-profit university to participate in NCAA Division I athletics.

The university’s website describes the transition this way: “A small group of investors acquired the university and refocused on online education for working adults. With an improving financial structure, the university recruited a new leadership team in 2008 to envision a future that centered around a hybrid campus strategy — combining traditional students with nontraditional students (primarily working adults studying at the graduate level). The university completed an initial public offering in 2008 to generate the capital necessary to improve its online infrastructure and expand its campus.”

Grand Canyon University arena today

By the university’s own accounting, more than $1 billion has been invested in the school, which now is the largest Christian university in the world. Under the new ownership, enrollment blossomed from fewer than 1,000 students to about 80,000 students — with about 19,000 students attending classes on campus and another 60,000 attending virtual classes from around the world.

The university reports that more than 47% of its online student body is studying at the graduate level.

In 2018, the university attempted to return to nonprofit status, with mixed results. The plan was to separate functions of the university into for-profit and nonprofit units. A publicly traded corporation, Grand Canyon Education Inc., provides certain services for the university. The university president, Brian Mueller, also serves as the CEO of Grand Canyon Education.

A regional accrediting agency and the IRS approved the return to nonprofit status for the university but the U.S. Department of Education has not. Critics of the move have charged that the reason the university sought to return to nonprofit status is to avoid paying more than $9 million annually in property taxes.

What’s next?

Although markedly different from the path most faith-based colleges and universities have taken or will take, Grand Canyon’s success illustrates the combined pressure of market forces on higher education today.

Two years ago, Barna Research produced an extensive study titled “What’s Next for Christian Higher Education? How Christian Colleges and Universities Can Prepare for the Future.”

Belmont University hosted one of this year’s U.S. presidential debates.

Its findings were summarized in an article published by Christianity Today: “The 18-month study showed that students at Christian colleges and universities are increasingly choosing secular careers such as business administration and teaching over careers in youth ministry or church administration. And, like students attending secular colleges and universities, they place spiritual growth low on their list of priorities when making their college plans.”

This shift in student interest was accelerated by the Great Recession of 2008, Barna found.

Barna’s research pointed out that “the big driver of motivation to go to college, in general, in North America is economic security,” said Ralph Enlow, former president of the American Association for Biblical Higher Education, which commissioned the Barna study. “That’s been the dominant theme at least since the Great Recession for the American public in terms of what they think the purpose of higher education is,” he told Christianity Today.

William Tibbetts, dean of the college of business and technology at North Central University in Minneapolis, told the magazine that his recent study of small, private liberal arts colleges, most of which are faith-based, found a growth in enrollment during the 10-year period after the recession.

“In the ’90s, universities were about investing in underground bowling allies, multiple Olympic-size pools, and student unions that would give the Taj Mahal a run for its money. It was all about appealing to the student experience,” he said. “Then the recession hit. Whereas before, the assessment of one’s college choices was about amenities and then, eventually, pricing, it came to be all about post-graduation life. In other words: job placement.”

With nearly a year of COVID restrictions, higher education is being reshaped again.

And now, with nearly a year of COVID restrictions, higher education is being reshaped again. As with nearly every other area of life, trends that already were in place have been accelerated by the pandemic. Among those is distance learning through online courses.

The race to build better buildings and create more community on campus has turned to a survival of the fittest based on an entirely different criteria — the ability to innovate on short notice and adapt to technology in a way founders of most faith-based colleges never could have imagined at the turn of the 20th century.