With increasing attention to the roots of American slavery in religious life, more churches and faith-based ministries that existed prior to the Civil War are unearthing truths they wish weren’t true.

Then the hard questions arise: How should a church, university or organization that discovers its founders or in rare cases even the organization itself owned slaves respond to such a revelation? How should such institutions respond when it becomes known that some of their buildings were erected by slave labor or financed by the sale of enslaved persons?

This is the dilemma currently facing Baylor University, where the board of regents recently released a 90-page report detailing the slave-owning history of its founders and a set of recommendations for response. Typifying the political divisions in America today over systemic racism, to some, the Baylor report and its recommendations go too far and to others the recommendations offer too little.

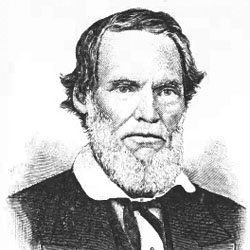

R.E.B. Baylor

One thing Baylor said it will not do is change the school’s name, even though there is documented evidence that its namesake, R.E.B. Baylor, was a slaveholder. The Baylor name also graces other prominent institutions in Texas, including the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor, Baylor College of Medicine, and Baylor Scott and White Health, the largest nonprofit health care system in Texas.

Wake Forest and Wingate

Soon after Baylor University’s announcement, Wake Forest University in North Carolina — which began as a Baptist school well before the Civil War — announced May 7 a major development from its Slavery, Race and Memory Project. The university will rename its Wingate Hall to May 7, 1860 Hall. The date reflects when 16 enslaved people were sold to fund Wake Forest’s initial endowment under the leadership of then-president Washington Manly Wingate.

Wait Chapel at Wake Forest University.

However, Wake Forest President Nathan Hatch said Wait Chapel — which is attached to the building currently known as Wingate Hall — will retain its name as a reminder of the slave-holding past of the school’s founders. Namesakes Samuel Wait and Washington Manly Wingate both were slaveholders.

Said Hatch of the dual approach to naming: “The complexity and contradictions create a tension that invites engagement with our story and the people whose lives are remembered and honored.”

The news from Wake Forest suddenly put the spotlight on another Baptist-founded institution in North Carolina, Wingate University. Although not founded until 1896, Wingate takes its name from the same Washington Manly Wingate associated with Wake Forest. He had been dead 17 years when the school adopted his name in tribute to his leadership among North Carolina Baptists.

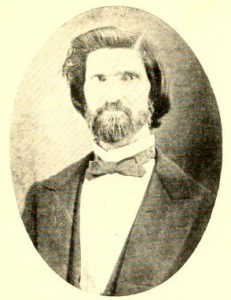

Washington Manly Wingate

In a news release, Wingate officials said: “Wingate President Rhett Brown recently became aware of the slave-owning past of the school’s namesake during a phone call with Wake Forest President Nathan Hatch. Washington Manly Wingate was a two-time president of Wake Forest University, and, according to Wake Forest sociology professor Joseph Soares, it was found that ‘every president of Wake Forest until the Civil War had enslaved human beings under him.’ That includes Manly Wingate.”

The news release added: “Knowing that the stain of past transgressions can never be eliminated and that the debt to people of color can never be repaid, Wingate University officials do believe this deeply upsetting news can serve as an opportunity for reflection, reconciliation and growth.”

The multi-campus university will appoint a group of faculty, staff, students, alumni, trustees and town officials to determine how to respond to this historical information about the namesake of both the university and the town where it is located.

Rhett Brown

“This truth hurts,” President Brown said. “It casts a shadow over our university, my alma mater, and is not in keeping with who we are today, what we value and how we strive to be more inclusive for the students who study here and the people who work here.”

Joe Patterson, chair of the Wingate board of trustees, added his own pledge: “While we can’t erase history, we can learn from it. The Board of Trustees eagerly awaits the group’s recommendations on how to move forward.”

When universities ‘discover’ their racist roots

To some, the idea that such historical information has been “discovered” at any institution or church belies a willful ignorance. Often, the information now coming to light has been readily available for decades, but no one in authority wanted to know it. Yet in other cases, information truly lost to the passage of time is now resurfacing as more people go digging up the past.

While universities most often land in the news for such historical research related to slavery, the same challenge presents itself to other faith-based nonprofits and even local congregations.

1792 engraving of Brown University campus.

Baylor and Wake Forest are far from the first faith-based school to unearth or acknowledge roots in racism and slavery. Some universities also have created plans for reparations once they’ve researched their past. One model for such is Brown University, which in 2006 issued a report about its founders’ connection to slavery. In response, the university created the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, which has been lauded as a model.

Other Ivy League schools also have undertaken similar tasks, including Georgetown, Harvard, and Princeton Theological Seminary. Others have not. The approaches taken by these schools have been both lauded and lamented.

While the slave economy funded many of the nation’s historic colleges and universities, at least two campuses are known to have been built by slave labor — the University of Virginia, and the College of William and Mary.

The journal Inside Philanthropy reports that the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2019 gave a $1 million grant to the College of William and Mary to support research and education pertaining to the college’s history with enslaved people. The cruel irony — or redemption, depending on perspective — is that the Mellon family reportedly includes ancestors who owned slaves.

Mercer University, a historic Baptist school in Georgia, is among 75 schools that have joined the University of Virginia’s Universities Studying Slavery consortium. This group is dedicated to sharing “best practices and guiding principles about truth-telling projects addressing human bondage and racism in institutional histories.” Its member schools are “committed to research, acknowledgment and atonement regarding institutional ties to the slave trade, to enslavement on campus or abroad, and to enduring racism in school history and practice.”

Mercer’s two origin stories

Mercer offers an interesting window into the complexities of collegiate histories and slavery because of its location in the Deep South — Macon, Ga. — and because of its connections to Georgia Baptists. Another twist for Mercer is that the school has two origin stories — one most certainly rooted in the realities of the slave economy and one rooted in the Reconstruction era.

The chapel at Mercer’s original Penfield campus is one of the few buildings still in use there.

The first Mercer story begins in 1833 in a place called Penfield, Ga., which is located about halfway between Atlanta and Augusta, Ga., and 70 miles northeast of Macon, Ga. The town was named for Josiah Penfield (born 1785), who gave $2,500 to the Georgia Baptist Convention with a challenge to match that amount and create an educational enterprise in what at the time was considered some of the richest farmland in America.

The Baptist convention amassed nearly 1,000 acres of land in and around the village and first opened a manual labor school for boys in 1833. It was named Mercer Institute, in tribute to Jesse Mercer, a local pastor who also was a major financial contributor.

The idea was that students would tend the fields part of the day and study part of the day, emulating a European model of work-study. That feature carried over even as Mercer Institute became Mercer University in 1838. By 1844, the manual labor department was suspended indefinitely, due to economic inefficiencies and the physical danger it presented to students.

Yet the students continued to be fed and housed, even after they stopped tending the fields and doing the manual labor. Who did that work? Who built the buildings? Who farmed the cotton? Penfield is located in Greene County, which fell within the heart of the old plantation culture with slavery as a way of life.

Archival photo of Mercer president’s home in Penfield, Ga.

And herein lies the historical problem with documenting the ways slavery made possible colleges and universities. While there is no record indicating that Mercer University owned slaves, scholars believe it is most likely that the school’s faculty and presidents did.

Mercer Institute, and then Mercer University, operated not just classrooms but a post office, bank, mercantile stores, print shops, hosiery mill and cotton warehouses on 450 acres surrounding the campus.

And in a quaint twist, Mercer in Penfield did not build dormitories. The Georgia Baptist Convention sold property to interested parties who would commit to live in Penfield and operate boarding houses for students. If those boarding house proprietors owned or rented slaves, the university’s hands would remain clean.

Mercer’s second origin story

Doug Thompson

In 1872, Mercer University moved to Macon, abandoning the Penfield campus. Thus, modern Mercer — its buildings and expansion — comes about after emancipation. And it is here that Mercer history professor Doug Thompson picks up the story.

“There are no buildings on our campus that would have had enslaved people building them because there was no slavery,” he said. And while that historical break from Penfield to Macon makes it easier to distance the school from ties to slavery, students increasingly want to know more about the university’s early history.

Archival photo of Mercer students visiting Penfield.

For decades, Mercer students have taken an annual pilgrimage to Penfield as part of the passed-down tradition. But until recently, deeper research on the Penfield story has not been done, in part because no one on the university’s history faculty is a 19th century American specialist.

One of the student traditions is to visit the graves of Mercer founders, such as Jesse Mercer. However, now there’s a new wrinkle with the recent rediscovery of a separate burial ground for African Americans that exists on the other side of a wall from the Penfield Cemetery. The burial ground holds perhaps hundreds of graves, including marked stones that identify formerly enslaved members of the community and their children.

In 2019, Mamie Hillman, director of the Greene County African American Museum, learned of the burial ground and now leads an effort to research and restore it. For Mercer students and alumni, this adds a new perspective.

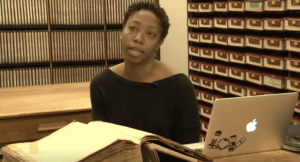

An inquiring alumna

Summer Perritt is a Mercer alumna who went to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland for graduate work and became interested in university connections to the transatlantic slave trade — also a current topic on that campus at the time. She communicated with her alma mater back in Georgia to ask whether anyone had ever traced its history related to slavery. The end result was that she wrote a master’s thesis on the topic.

Summer Perritt

“She uncovered a lot,” said Thompson, who noted that before the coronavirus pandemic changed everyone’s agenda, “we were picking up her work and formulating a proposal to take before the president.”

As a result of Perritt’s research, Mercer’s Student Government Association “became very interested and said we’ve got to tell a better a story about Penfield,” he explained. Whatever the school’s history has been, its present-day reality is one of intentional integration and equality, with 28% of the student body being Black. Mercer integrated its student body in 1963.

“There has been a push for universities to begin this work for almost two decades now, but a lot of places have been reticent to begin the process, Mercer included,” Perritt said. When she got to Edinburgh, she took a class on slavery and universities, which prompted her to learn more about her own alma mater.

“I felt compelled to see some recognition for those enslaved people who helped build the very institution I had attended,” she explained.

What Mercer is doing now

All this prompted Mercer to join the Universities Studying Slavery consortium. That work will be run through Mercer’s King Center for Southern Studies, which was created in 2014 with a challenge grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The King Center’s website lauds Perritt’s master’s thesis as a prompt for further research. “There is more to uncover and explore in the description of the physical space at Penfield and the financial structure that allowed the institution to grow,” the site says.

Slaves on the cotton plantation of Samuel T. Gentry, Greene County, Georgia, ca. 1850. Daguerreotype, quarter plate. The Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

It adds: “Financial records document that the college rented enslaved people who lived and worked on the campus at Penfield. Where the university housed them on the original campus remains unclear. We also know that the holding of enslaved persons built much of the wealth of Mercer’s founders and benefactors. A fuller exploration of Mercer’s slave past will help us understand the nature and purpose of a Baptist education that required graduating students to defend the institution of slavery in the early 1860s curriculum.”

This research also will seek to understand what daily life would have been like for students, faculty and staff in Penfield. “Given the proximity of the African American cemetery to the cemetery of the founders of Mercer, we can deduce that their interactions were daily and constant, but we do not yet know the fuller story,” the King Center website says. “Mercer’s initial vision for this work is an accounting for the geography of slavery at Penfield and then how that geography shifted in the post-Emancipation world, first while still in Penfield and then with Mercer’s move to Macon, Ga.”

Not just in the South

While observers might think historic connections to slavery would be limited to the American South, that is not the case at all. In fact, the connections are not even limited to America.

This is true because of the power of the slave economy, which pumped money into institutions well beyond the South, and because of historical figures in Europe and the American North who enabled the slave trade.

That was the case in Edinburgh, Scotland, for example, where Perritt first came to be interested in this research.

“Slavery was an incredibly pervasive system that affected almost every aspect of life for Americans, no matter where they lived. Even those who never enslaved people still benefitted from an economy that depended on their stolen labor,” Perritt said. “The same is true for other countries, even ones we don’t typically associate with slavery.

“Many of the donors I looked at either profited from plantations in the Caribbean, had family members who did, or were involved in the slave trade in some capacity, but few ever enslaved people in their own right.”

“As an example, in the work I did for the University of Edinburgh, I looked at the original donors who contributed to the construction of the university. Many of the donors I looked at either profited from plantations in the Caribbean, had family members who did, or were involved in the slave trade in some capacity, but few ever enslaved people in their own right.”

An irony of this finding is that Scotland often is lauded for its role as a refuge for abolitionists like Frederick Douglass. That’s how pervasive the slave economy was at the time.

“Most schools that were created prior to the abolishment of slavery, and even some after, had some dealings with slavery,” Perritt said. “Be they as explicit as the university actually enslaving people in their own right, or more commonly, being run by leaders who profited from the institution of slavery in some capacity. All these connections, no matter how small, are still significant to the memory of those Black people who were exploited, and all these schools have an obligation to recognize their role in that exploitation.”

Brown University

That’s also how Brown University — located in Providence, R.I. — came to be implicated. Brown, the nation’s seventh oldest university, was chartered in 1764 with an initial mission to train Baptist clergymen.

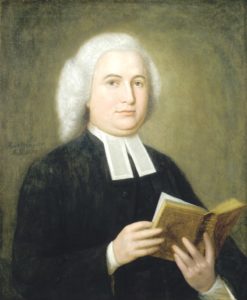

“The school’s founding documents contain no references to slavery, which most at the time regarded simply as a fact of life, irrelevant to the university’s mission,” noted a report of the university’s Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice in 2004. “If any contemporaries were surprised or troubled when the school’s first president, Rev. James Manning, arrived in Rhode Island accompanied by a personal slave, they seem never to have said so publicly.”

Brown University’s first president, minister James Manning

Initially, Baptists were guaranteed a majority of seats on the university’s board of trustees, with smaller allocations for Congregationalists, Anglicans and Quakers. And among these, “the presence of slave traders among the group occasioned no discussion,” the report stated. “While no precise accounting is possible, the steering committee was able to identify approximately 30 members of the Brown Corporation who owned or captained slave ships, many of whom were involved in the trade during their years of service to the university.”

So here, in the Rhode Island colony, where slavery was legal until 1843 but not as prevalent as in the South, religious leaders and university founders were engaged in making the slave trade possible and benefited from it financially. Which also means Brown University was funded — and continues to benefit today — from the ill-gotten gain of human trafficking.

This is the story most colleges and universities that predate emancipation either don’t know or don’t want to hear.

“It isn’t that you consciously don’t think about it; it’s that you don’t consciously think about it. Then something forces you to have to think about it.”

Thompson, the Mercer history professor, summarizes the challenge to white leaders of universities about this upending historical research: “It isn’t that you consciously don’t think about it; it’s that you don’t consciously think about it. Then something forces you to have to think about it. Then how do you respond once you know?”

Not just a challenge for universities

Knowing or unearthing histories with ties to racism or slavery is not just the domain of colleges and universities, however. Some faith-based social service ministries — or their founders — also predate the end of slavery.

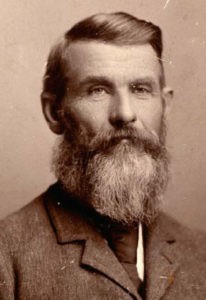

One of the largest of those is Buckner International, based in Dallas. Although Buckner Orphans Home was not formally organized until 1879 — 14 years after the 13th Amendment outlawed slavery — its founder and namesake, R.C. Buckner, was a well-known Texas pastor well before then.

R.C. Buckner

In 2020, modern-day Buckner leaders received the shock of a lifetime when they were presented historical evidence that “Father Buckner,” as he was known, had owned at least one slave in his lifetime. An 1860 “slave schedule” from Lamar County, Texas, lists Buckner — who then was pastor of First Baptist Church in Paris, Texas — as the owner of an enslaved 16-year-old Black female.

How Buckner responded

Soon after this revelation, Buckner CEO Albert Reyes released a video statement about the finding, and the organization’s board of directors took formal action to address it.

“Regardless of who we are, our past shapes us and influences us,” Reyes said in the video. “Today while we recognize the global impact of Buckner, we’re also faced with a fact of history that only recently came to our attention. And we’re reminded that history is, indeed, painful at times.”

To say that R.C. Buckner is a historically revered figure in Texas Baptist life would be vast understatement. This is the man who after the great Galveston hurricane of 1900 traveled by train to the devastated city and rescued children left parentless by the storm. This is the man who started the first Black high school in North Texas and the first orphanage in Texas that admitted Black children. He was the founder of the first Black Baptist association in the state of Texas.

Albert Reyes

Reyes and the Buckner board did not run away from the news of their founder’s slave-holding history, nor did they seek to explain it away. They barely understood how it could be possible, yet the historical documentation was verified.

“We cannot vindicate history, nor can we vindicate those who lived it,” Reyes said in the video. “Slavery in America was one of the vilest sins ever perpetuated against humanity. It was wrong. And those who own other human beings cannot and should not be given a pass. We owe it to the enslaved people of the past and their descendants to openly acknowledge this evil.”

He added: “While we are disappointed with R.C. Buckner’s human failure, we nonetheless remember the impact of this ministry throughout 14 decades and we rejoice for those whose lives have been changed.”

The Buckner board quickly adopted a statement repudiating “racism, injustice and racial inequality” and pledging to ensure the organization’s racial diversity.

“Slavery in America was one of the vilest sins ever perpetuated against humanity. It was wrong. And those who own other human beings cannot and should not be given a pass.”

“As an organization, we denounce racism in all its forms as being inconsistent with Scripture and with Buckner’s Christian mission,” the board said.

The Baptist Standard reported Board Chair Rodney Henry explaining: “Buckner has a strong history of racial inclusion among our staff and those we serve, but our board wanted to publicly affirm where we stand on this issue. We wanted a statement that clearly articulated our views about the evils of racism and one that calls for action.”

Reyes noted that the organization’s workforce — including him — is 67% non-white and the majority of clients served are persons of color.

“We’re by no means perfect, but we have done some things right,” he said. “Still, we realize that this is more than a fad or a temporary issue. As followers of Jesus, our board and the organization must keep justice and racial reconciliation front and center.”

Where are the stories of other nonprofits?

Surely there are other examples of faith-based institutions like Buckner addressing their racist pasts, but such examples are not easily identified in public statements. Of all the church-related children’s homes, hospitals and charities birthed before the end of slavery, Buckner appears to stand alone in public statements about past ties to slavery.

Valerie Cooper

That’s not surprising to Valerie Cooper, associate professor of religion and society and Black church studies at Duke Divinity School. As one of the nation’s leading academics on this subject, she knows most institutional leaders don’t want to know the details of the past because then they will have to address hard issues.

Yet more and more details are coming forward today, and as other scholars have noted, most of that information is standing in plain sight. It is so easy to find that even “non-specialists are finding it,” Cooper added.

Churches with slave histories too

Nor are the historical skeletons of slavery limited to educational and charitable organizations. Churches and pastors of churches are implicated by historical records as well.

Writing about American slavery in 1842 (The American Churches, The Bulwarks of American Slavery), James Gillespie Birney gives real-time context to the situation.

“Ministers and office-bearers, and members of churches are slave-holders — buying and selling slaves, (not as the regular slave-trader,) but as their convenience or interest may from time to time require. As a general rule, the itinerant preachers in the Methodist church are not permitted to hold slaves — but there are frequent exceptions to the rule, especially of late.”

“Instances are not rare of slave-holding members of churches selling slaves who are members of the same church with themselves.”

Birney reports that of the estimated 2.5 million slaves in the United States at the time, 80,000 were members of the Methodist church, 80,000 of the Baptist church and 40,000 of other churches. Then he explains: “These church members have no exemption from being sold by their owners as other slaves are. Instances are not rare of slave-holding members of churches selling slaves who are members of the same church with themselves. And members of churches have followed the business of slave-auctioneers.”

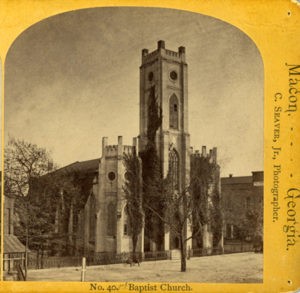

First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon

When Scott Dickison arrived as pastor of First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon, Ga., in 2012, he quickly learned the historical connection of his congregation to the other First Baptist Church located across a parking lot. As is true across the South, his church is the white First Baptist Church; the other is the Black First Baptist Church.

In time, Dickison and James Goolsby, pastor of the historic Black congregation, became friends, led their congregations to work together and became a national model within a racial reconciliation movement known as the New Baptist Covenant. But that was only the beginning of the story that needed to be told.\

In time, Dickison and James Goolsby, pastor of the historic Black congregation, became friends, led their congregations to work together and became a national model within a racial reconciliation movement known as the New Baptist Covenant. But that was only the beginning of the story that needed to be told.\

By 2016, Dickison and Thompson, the Mercer history professor who also is a member at First Baptist Church of Christ, wanted to know more about the church’s possible connections to slavery. The church was founded in 1826 in a region dependent on the slave economy.

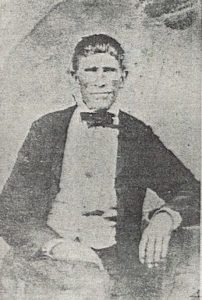

What they soon learned was shocking if not surprising: Five of the six founding members of the church were slave owners. Some owned several slaves, some just a few. “One of our early pastors, Charnick Tharp, owned a pretty sizable plantation where he owned a great many enslaved people,” Dickison explained.

Charnick Tharp, slave-owning pastor of First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon, Ga.

The church’s history remembered Tharp as being so generous that he didn’t accept a salary from the church. But there’s a reason he could do that: He likely was the wealthiest person in the church because he owned a plantation and hundreds of slaves.

And while that fits the imagined profile of America’s slaveholders, Tharp’s story is not the most common connection between churchgoers and slavery, Dickison explained. “When we think about slavery, we think about these large plantations. And that was not the case. It was way more common for middle-class folks to own slaves.”

One historical illustration makes this point clear.

Dickison and Thompson began digging into the public records related to the church and its early 19th century members. They cross-referenced church membership rolls with public records at the county courthouse. That’s how they learned about Mary Lamar.

The Lamar family gave the land for the Black First Baptist Church to erect its own worship space, and they were regular donors to the white church, where they were members.

“We found records where Mary Lamar had sold two enslaved teenagers, and such and such amount of money given to different church funds,” Dickison said. “It was very clear … all the money was wrapped up in the slave trade. To see it laid out there with names attached to it was very shocking.”

The grand sanctuary of First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon, Ga., circa 1876.

Then, applying some basic logic led to the next discovery. In the 1850s, the white Baptist church built a grand new sanctuary that was hailed as the “jewel” of the frontier city. Where did the money come from? How was the construction project financed?

“There has not been a lot written on how churches were built and paid for in those days,” Dickison noted. “How did churches pay for those things?”

Cross-referencing data from the church records with county records provided the answer.

A Mercer University student interviewed on local TV, Channel 13 WMAZ, about her work preparing slave records and other documentation for digitization at the Bibb County Courthouse in Macon, Ga.

“It is entirely likely that they sold enslaved people and gave the proceeds to the church. Or it was made possible by their habit of mortgaging enslaved people,” Dickison said. “That church building would have been financed or mortgaged by the sale of its own members.”

This was before the separate Black church was built, so the enslaved Blacks would have worshiped at the white church attended by their owners — who sometimes sold their fellow worshipers to give money to the church.

Dickison included this information in a sermon he preached in March 2016. “You could hear a pin drop in there, and there were audible gasps,” he reported.

How the church responded

This new information came to light just as the church was revving up conversations on another controversial topic, human sexuality and LGBTQ inclusion. So the question of how to respond to the slave history got put on hold. By the dawn of 2020, the church was ready to talk more about its history, and then the global pandemic hit.

Now it’s time to pick up the conversation. “We’re going to have to reckon with that past,” Dickison said. “What is owed is a question that is very important to me.”

One part of that response is sanctioning more research to be able to tell the story as fully as possible.

“We have recruited lay volunteers who will be trained on how to access these public records and cross-reference our archives and see what additional information we can turn up,” Dickison reported.

Archival photograph of slaves in Bibb County, Ga.]

“I see this as a kind of honest accounting of all that we’ve been handed down. I don’t think it’s fair any more just to talk about the rich inheritance we’ve received as congregations and not talk about the unsavory parts of that history that have been gifted to us.

“What are we afraid of ultimately?” Dickison asked. “This has been an unbelievable opportunity for us to encounter the gospel in a new way. … The path to salvation, this is what we’ve talked about. Honest confession and accounting. Only then can you really open yourself to repentance and reconciliation. We have the language available to us to understand what this work means. As hard as it’s been, as painful, and as much as it has been a point of contention, it’s also been a source of spiritual growth.”

And his church is by far not the only one that needs to do this kind of work, he added. “Our story is valuable not because it is unique but because it is representative. In Macon, every major denomination has the same story here. That’s true all over the South.”

What is an appropriate response?

Churches and universities are late to the discussion about historical ties to slavery, said Perritt, the Mercer grad who studied at Edinburgh. That’s partly due to the fact that “white Americans’ perception of slavery and racism has evolved over time. Unfortunately, this changing perspective and the recognition of slavery’s continuing effects has been slow and remains a process even today.”

However, renewed calls to address the wrongs of the past are proving to be good for universities in ways their administrators might not have thought.

“Some university administrations have ignored their institution’s connections to slavery in an effort to avoid what they see as an embarrassing and potentially costly affair. Oddly enough, I have found the opposite to be true in my personal experience. Those schools that have acknowledged their participation in the institution of slavery and have devoted resources to further research in earnest have almost always been viewed more favorably, at least by student populations.”

“Respectfully talk to Black Americans within and around your school’s community. This is their history, and they should get to decide what is done with it.”

“The best course of action, in my opinion, is for a school to openly and readily acknowledge its connections to slavery,” Perritt advised. “Further ignoring or denying such information only reinscribes trauma, both to the memory of the people they exploited and potentially to their current Black student populations.”

Once a school has acknowledged its role in slavery, there are many ways to move the conversation forward, Perritt said. “First and foremost, schools should devote additional resources to further research. There is always more to the story. Beyond that, I think the best step is to seek out professionals who have experience in these fields. Talk to historians who have the necessary background and expertise to properly contextualize a school’s history with slavery, talk to public historians who can determine the best ways to present this information to the public, talk to students who can tell you what they would like to see done with the new information.”

And above all else, she said, “respectfully talk to Black Americans within and around your school’s community. This is their history, and they should get to decide what is done with it.”

Listening to Black Americans

Many Black Americans feel like they’ve been talking about these problems for years but white people haven’t listened or cared. And there is danger in drawing attention to these easily documented facts just because some white folks suddenly got interested.

Judge Wendell Griffen

“Black perspectives are required on the issue” said Wendell Griffen, a judge and Baptist pastor in Little Rock, Ark., who has been a vocal advocate for social justice. “Baylor University, Princeton Theological Seminary and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary’s recent ham-handed efforts amply show how white leaders are ethically compromised about the subject of the complicity of their institutions in chattel slavery and exploitation of Black lives and labor.

“Only the morally obtuse or perverted would reason that successors to the Nazi regime were competent to investigate and decide the outcome of claims of atrocities committed by people complicit with the Nazi regime,” he added. “Yet, white Christian leaders claim to be morally and ethically fit to do the comparable work concerning the involvement of their institutions with slavery and its aftermath.

“I have maintained for more than two decades that the decisions about how to remedy historical injustice must be driven by the perspectives of the descendants of the victims of those injustices, not by the descendants of people who benefited from it.”

Even denominations and seminaries that consider themselves liberal or progressive are at fault on these issues, said J. Alfred Smith, pastor emeritus of Allen Temple Baptist Church in Oakland, Calif. He found this to be true on the West Coast, far from the historic ties to slavery in the American South but close to other forms of historic racism mainly targeting Asians.

J. Alfred Smith Sr.

“The West Coast seminaries that are mostly liberal have a kind of silent complicit liberalism that’s not willing to take on the history of their past or willing to look at it because it’s too painful and ugly for them,” Smith said. “Or they sanitize and baptize it with the theology of white exceptionalism. They criticize their more conservative brothers, but in terms of having a theological curriculum where the works of Black authors are read and where Black faculty are respected and their courses are not electives but are part of the core curriculum, that’s what I find missing.”

What about reparations?

Inevitably, the conversation at churches, institutions and schools uncovering their historic ties to slavery turns to one difficult word: “reparations.” That word alone incites controversy and political divisions.

White people often dismiss talk of reparations on the basis of the passage of time. Slavery was made illegal in the United States in 1865 — nearly 160 years ago. A typical response might be: “What responsibility do I have for the sins of ancestors so far removed I never knew them?”

Perritt, the Mercer grad, believes the effects of slavery are still being felt in the present day.

“Things like a lack of generational wealth and an abundance of generational trauma are just two of the continuing side effects of slavery for Black Americans,” she said. “Universities that preach diversity and inclusion should feel obligated to address the systemic causes of inequality that they have historically participated in.”

“Universities that preach diversity and inclusion should feel obligated to address the systemic causes of inequality that they have historically participated in.”

That sentiment is shared by Cooper, the Duke Divinity School professor.

“One of the things that racism and Jim Crow and slavery did was to inhibit their ability to have wealth and to pass it on,” she explained. And this has simple yet overlooked implications today, such as explaining why so many Black people are in jail simply because they can’t pay bail. White people in similar circumstances get bailed out. Black people accused of crimes and awaiting trial are less likely to be able to post bail.”

“Historic inequality means that people of color end up with less money on the dollar and a million ways for our money to be stolen from us,” she continued. “Unless we fix a wicked system that allows people of color to be exploited, the minute we give people of color money there will be people to steal it from them.”

Therefore, reparations in the form of some direct payment is not enough, the professor said. “Reparations must address the system.”

Sometimes appropriate reparations are not even called “reparations,” Cooper added, explaining that university and seminary admissions policies need holistic overhaul not only to admit Black students but to help them thrive once enrolled. Especially in schools that were built on the backs of Black forebears.

For schools as well as churches, “the answer is not only to accept Blacks as members but also to empower some Blacks to become leaders,” she said.

Another form of reparation is to honor the legacy and memory of the forgotten Black slaves who have been whitewashed out of institutional histories.

At least 67 graves have been identified in this slave cemetery excavation at UVA. (Photos by Cole Geddy used courtesy of UVA Magazine)

For example, at the University of Virginia, excavation for a building project in 2011 revealed nearly 70 graves — previously unknown in modern times — in the direct path of the new construction. Eventually, the university administration was persuaded to change the building plans and avoid covering up the burial site.

UVA — where as many as 5,000 enslaved people are believed to have worked — last year dedicated a $6 million memorial called Memorial to Enslaved Laborers that not only honors the past but helps tell the story of those enslaved workers.

A difficult call for churches

When churches with congregational polity — like Baptists — attempt to address racism and slavery in their past, the pastors have no real incentive to lead the charge, Cooper noted. “In churches where the polity is congregational, you can get fired for getting on the wrong side of a congregation. There is absolutely no incentive to speak on race or on any issue that makes your members angry.”

This is not a new phenomenon, she added. “In the South, Jim Crow was upheld not because everybody believed in it but because too many people were afraid to challenge it. Part of the difficulty for Baptist churches is the polity that keeps Baptist pastors tied to pleasing rather than prophetically challenging their members.”

“In the South, Jim Crow was upheld not because everybody believed in it but because too many people were afraid to challenge it.”

Cooper, who is a United Methodist, said the incentives against prophetic church leadership extend to nearly all denominational groups, even those with hierarchical governance. “In addition to throwing you out, people can close their checkbooks.”

Are reparations biblical?

White church leaders who don’t want to talk about the legacy of racism and slavery may proffer a variety of excuses for why they want to look the other way. Cooper wants them to know, however, that reparation is a biblical mandate.

“It’s clear that the biblical text (Luke 19:1-10) mandates what we would call reparations,” she said. “When Jesus calls Zacchaeus out for everything he has stolen as a tax collector, Zacchaeus proposes to make financial restitution. Matthew’s Gospel (Matthew 5:23-24) says if you get to the altar and realize your brother has something against you — not that you have something against your brother — go and make it right.”

This is different from the theology of American individualism, which “tends to emphasize our relationship with God and neglect the part Jesus preached about, our relationship to our brother,” Cooper said. “Reparations is what you do to make your community whole. It’s the work of Zacchaeus. Not to win heaven, but to win earth.”

Architect’s rendering of the Slavery Memorial at UVA.

And for evangelicals who are concerned about winning the world to faith in Christ, reparations ought to be a good incentive, the professor continued. “Right now, Christianity is not doing a particularly good job of recommending God to the world. Wouldn’t you like us to do better?”

Instead of owning up to the history and repercussions of racism, “white America is saying, ‘We’re not racist!’ as though saying it louder makes it true.”

Revival in America will not happen without addressing racism and slavery, Cooper asserted. “If you look at the history of American revivalism, they were all times when everybody was welcome. It is my opinion that God doesn’t send the Holy Ghost to where all people are not welcome.”

A church makes reparations

Beginning in 2018, First Church in Cambridge, Mass., modeled what the work of reparations might look like in a local church through a Louisville Institute-funded project titled “Remembrance and Reparation at First Church.”

The congregation, which dates to 1636, studied its history with regard to slavery and race in the context of Colonial Massachusetts. Led by Pastors Dan Smith and David Kidder, the church studied the congregation’s minutes, identifying how the church treated Black and indigenous persons of color who sought membership. They studied how ministerial leadership addressed questions of slavery and whether or not they themselves owned slaves.

The historical study found the congregation was “slow to address the challenges of abolition and a growing Massachusetts population of free Black persons.”

The historical study found the congregation was “slow to address the challenges of abolition and a growing Massachusetts population of free Black persons.” Even as Northern opinions regarding slavery began to change, “Black families found more welcoming options in the growing number of predominantly Black churches in New England.”

Following this historical work of remembrance, in 2019, the congregation turned toward studying the matter of reparations. They studied the theological and biblical basis for which a congregation might participate in the work of reparations. Pastors Smith and Kidder led the congregation in discussions regarding national and public reparations.

First Church encouraged individuals to take a personal reparations pledge with the organization FOR Truth and Reparations, a grassroots organization dedicated to encouraging “individuals, businesses and institutions of moral conscience to reflect on their unfair advantages and do their part in redistributing value to people who have less because of generations of structural discrimination and political inequality.”

In June 2020, First Church adopted a statement on “Becoming an Anti-Racist Church,” and their work is ongoing. In their statement, they acknowledged “the problem of racism is a white person’s problem and that this is white people’s work.” The work is both personal and communal.

Necessary discomfort ahead

One of the hardest parts of discussing historic ties to slavery and racism for white Christians is that it puts them in the uncomfortable position of asking forgiveness from Black people.

“America requires performances of forgiveness from Black people, so that white Americans don’t have to be afraid of our anger,” Cooper said. “Can you think of a single example of a performance of repentance by whites?”

“Most whites have never been in a situation where they’ve had to be directed by Blacks, led by Blacks.”

As an example, after the murder of nine people at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., in 2015, reporters quickly asked the Black survivors and family members of the Black victims if they would forgive the white shooter. “In some cases, that happened before the bodies were even cold,” Cooper recalled.

This expectation of a one-way street on asking forgiveness also makes it difficult for white people to sit down and let Black people suggest a course of action to address historical wrongs.

“Most whites have never been in a situation where they’ve had to be directed by Blacks, led by Blacks,” Cooper said. “So this will require submission. Part of the work is just putting yourself in places you’ve never been and working through that discomfort of not being the leader, not getting to make the choices. That’s also part of reparations. … Honoring people who don’t look like you has a spiritual benefit.”

The portion of this article about First Church in Cambridge was reported by Andrew Gardner and originally appeared in a separate article published by BNG Aug. 5, 2020.

Some suggestions for further reading:

- “When Book Reviews Go Wrong,” a review in The Economist review of Ed Baptist’s book, The Half Has Never Been Told.

- The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, by Ed Baptist.

- “Black Deaths Matter, Too: Doing Racial Reconciliation after the Massacre at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina,” in Racial Reconciliation and the Healing of a Nation: Beyond Law and Rights, edited by Austin Sarat and Charles Ogletree.

- “The ‘Not Here’ Syndrome,” Stanford Social Innovation Review.

- “Judgment Days,” Washington Post.

- “Christian leaders wrestle with Atlanta shooting suspect’s Southern Baptist ties,” Washington Post

- “The Game Is Changing for Historians of Black America,” The Atlantic.

- “These student journalists are investigating a slavery burial ground on their college campus,” Poynter Institute.

- “An Old Love for New Things: Southern Baptists and the Modern Technology of Indoor Baptisteries,” Journal of Southern Religion.

- “Unearthing Slavery at the University of Virginia,” UVA Magazine.