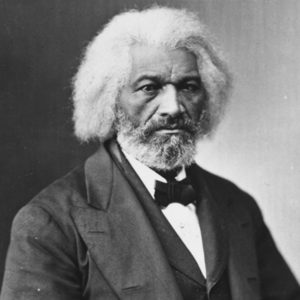

On July 5, 1852, the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester invited Frederick Douglass to give a speech on the 76th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, which became known by its central piercing question, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?”

Never one to sugarcoat his message, Douglass handed the good-willed ladies of Rochester a stinging indictment of the hypocrisy in white American celebrations of independence:

I am not included within the pale of (your) glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me.

This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?

Frederick Douglass

But Douglass also held out hope that the United States might yet live to be a nation worthy of its professed values.

“Notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation,” he declared, “I do not despair of this country.” Even while exposing their blind spots and contradictions, Douglass thought it appropriate to honor the memory of the “statesmen, patriots and heroes … for the good they did, and the principles they contended for.”

Douglass was asking his white audience to hold their naive patriotism up next to his dissonant reality, not to cast shade but to light the road yet to be traveled.

More than a century later, in the South of my childhood, the contradictions between the principles of equality enumerated in the Declaration of Independence and the glaring racial inequities permeating our community remained hidden in our Fourth of July celebrations. On the Sunday closest to the holiday, our whites-only Southern Baptist congregation sang patriotic hymns, heard a sermon extolling the virtues of the nation and the promise of Western civilization, and on occasion began the service with a military color guard marching the American and Christian flags down the center aisle of the church. The soldiers parted like the Red Sea before the Communion table and flowed up the blue carpeted steps, where they planted each flag in gleaming brass stands that flanked the pulpit. The Fourth of July was our holiday, proudly celebrating our rightful inheritance of the American promised land.

But what, to the white American, is the 19th of June? Unlike most white Americans, I grew up with a vague awareness of Juneteenth (the name derives from a shortening of “June” and “nineteenth”), due to two coincidental factors. First, June 19 is my birthday. And second, I spent my preschool years in Texas, where the holiday was most prominently in the public eye.

“Of course, Juneteenth has everything to do with us.”

Leading up to my birthday, I occasionally saw signs around town announcing upcoming public Juneteenth celebrations. I was mildly fascinated, as young children are, with the juxtaposition of any other celebration with my birthday. But I also was told this was a holiday Black people celebrated. Juneteenth was their holiday. It had nothing to do with us.

Of course, Juneteenth has everything to do with us. And on June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden made it official, signing legislation making June 19th a national holiday for all Americans.

But there are still obstacles blocking the acceptance and celebration of Juneteenth by white Americans.

First, white Americans still have to grasp the significance of the historical event behind the holiday, which is admittedly complicated. Unlike Martin Luther King Day, which honors the legacy of a person from recent history, who can be seen in television footage and engaged through a body of writing and speeches, Juneteenth commemorates an event from the messy final stages of the Civil War. While President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued on Jan. 1, 1863, had technically freed enslaved people in Texas, this news had been both suppressed and ignored in this most westward state of the Confederacy for the final two and a half years of the war.

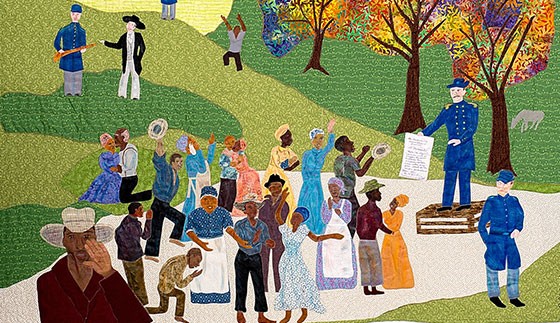

Juneteenth celebrates the date — June 19, 1865 — when U.S. Major Gen. Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3, which declared to the people of Texas that “all slaves are free.”

Traditionally celebrated by African Americans, especially but not exclusively in Texas, Juneteenth is the oldest celebration of emancipation from slavery in the country. It was the final exorcism of the evil institution that had plagued our young nation for its first century and poisoned these lands since first European contact for nearly three centuries prior to that.

While at least some African Americans grew up celebrating Juneteenth with family picnics, concerts, special worship services and storytelling, most white Americans had little awareness of, and almost no experience with, the holiday. While this disconnect creates some hurdles for the holiday being integrated broadly into American culture, it also presents an opportunity.

In a recent conversation, my good friend Jacqui Lewis, the innovative senior minister of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City, suggested that because of its proximity to Independence Day, both temporally and conceptually, our newest federal holiday has powerful potential to help rehabilitate the Fourth of July from the jingoistic Christian nationalism it all too often evokes. I’ve been thinking about that insight a lot over the past few days.

As we head toward my birthday and Juneteenth this year, and as I’ve been wrestling with my own uncertainty about how to mark the holiday, I’ve realized one model for creating what we might call a new “season of critical patriotism” can be found in the Jewish High Holy Days. Among the many gifts of being in an interfaith marriage is the ongoing invitation to experience and learn from a tradition that is not your own.

“We could conceptualize this season as the ‘days of freedom and equality,’ anchored by the Juneteenth proclamation that all are free and the Independence Day declaration that all are equal.”

As I’ve participated in this annual season of reflection over the last 20 years, I’ve been moved by the power of the moral space that opens in the 10 days between a celebration of the promise of the new year on Rosh Hashanah and lament over the failings of the past at Yom Kippur. The sweetness of apples, honey and kugel foreshadows repentance, fasting and atonement. Like binary stars, these holidays orbit one another, generating a contemplative space between them known as the “days of awe.”

The period of 15 days that span the space between Juneteenth and Independence Day could similarly function as an enduring season of critical patriotism for our time. Alongside the celebratory fireworks and other well-established practices surrounding the Fourth of July, we could develop new rituals that include the creative interplay of lament and celebration, reckoning and repair, truth-telling and dreaming.

Borrowing from the high holidays model, we could conceptualize this season as the “days of freedom and equality,” anchored by the Juneteenth proclamation that all are free and the Independence Day declaration that all are equal.

We also could embrace a conviction that is deeply engrained in Judaism, Christianity and indeed most religious traditions — that no people can live with integrity into the future if they cannot face failures to live up to their principles in the past.

Such a reconfiguration of Independence Day is also well-suited to help us cope with a dilemma created by our current era of historical reckoning. Fairy-tail narratives of impossible national innocence are thankfully no longer credible, particularly to nonwhite or non-Christian Americans or to most Americans under the age of 40. But in the harsh light of historical indictment, we also risk losing sight of our better angels and noble principles still waiting to be realized.

Conceptualizing the 19th of June and the Fourth of July together, in a creative mutual orbit where each is held by the gravitational force of the other, can help us develop rituals and stories that are honest about our country’s failings while also being hopeful about its possibilities. Beginning this season with Juneteenth can help us — especially white Americans — recalibrate Independence Day, as Douglass admonished his fellow Americans to do, as an opportunity to conduct a more forthright assessment of America as a work in progress. Such a season of critical patriotism would be one all of us could embrace.

Robert P. Jones

Robert P. Jones serves as president and founder of PRRI and is the author of The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy and the Path to a Shared American Future and White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, which won a 2021 American Book Award.

This column originally appeared on Robert P. Jones’s substack #WhiteTooLong.

Related articles:

Opal Lee may be the ‘Grandmother of Juneteenth,’ but she’s not done working for justice yet

Juneteenth and the promise of freedom | Opinion by Darrell Hamilton II

One year later, awareness of Juneteenth is growing

Juneteenth should remind us of all the things we don’t know | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Don’t keep sweet: Why white Christians need to celebrate Juneteenth | Opinion by Erica Whitaker