From the successful unionization of Starbucks baristas in Buffalo to striking actors and writers in Hollywood, support for labor unions is on the rise in a post-pandemic world. A Gallup poll from August reported 67% of Americans approve of unions and believe they help their members and the economy. In the UK, trade unions are entering a new “golden age” as union membership grows for the fourth year in a row.

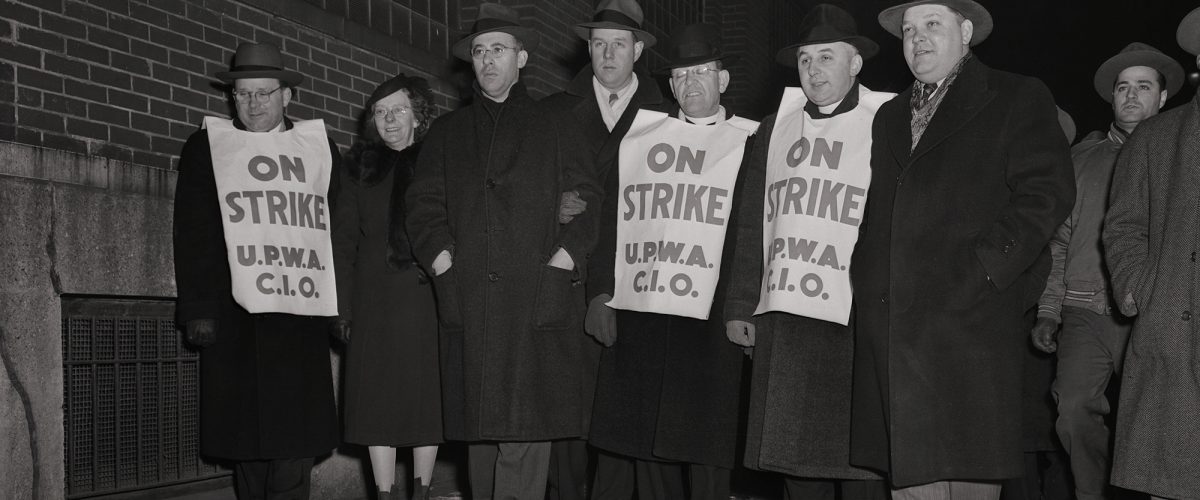

Historically, the church has played a significant role in the establishment of unions on both sides of the Atlantic. Many of the 19th century union founders and presidents in the UK were Methodist ministers. They patterned their trade union meetings after Methodist church services, complete with hymns and prayers, and borrowed the denomination’s tiered structure as an organizational model.

“Historically, the church has played a significant role in the establishment of unions on both sides of the Atlantic.”

At the same time, U.S. Baptists supported America’s burgeoning labor movement. State Baptist newspapers argued workers had the right to organize as long as they did not harm property or jeopardize public welfare. The democratic nature of labor unions resonated with the Baptist belief in the equality of all members within the congregation.

In 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. called for churches to “stop talking so much about religion and start doing something about it,” including fighting the evils of “monopoly-capitalism,” which he said churches had sanctioned far too long. King was participating in the Memphis sanitation worker strike when he was assassinated.

More than 50 years later, the prophetic spirit of his fight lives on. In 2008, a Smithfield pork processing plant voted to unionize thanks in part to the work of William Barber and other clergy. The AFL-CIO partners with clergy of all faiths to promote fair labor practices and the right to unionize.

Unionized clergy?

But what about the clergy themselves? Could pastors and priests soon be walking a picket line?

One-third of clergy members in the U.S. have thought about leaving the ministry. For those under the age of 45, the share rises to 46%. These numbers continue to climb even after churches appear to have rebounded from the pandemic.

What hasn’t recovered, however, are the systemic problems laid bare by COVID, such as sexism, racism, political division, classism and homophobia. When pastors attempt to address these issues in light of the gospel, their efforts often are met with bullying and threats of removal.

What’s true in the U.S. also is true in the UK where Rector Sarah Jones, who oversees three benefices in Ross-on-Wye in Herefordshire, resides.

“People nowadays expect and demand a quick response if they contact you. And there are some people who seem to feel free to express their anger to clergy in a way they would never do to someone else,” she said.

Priests in the Church of England also face stress from diocesan leadership. Bishops are closing many local churches and evicting junior clerics and their families from parsonages. The Church of England’s “managerial approach” to reorganizing its churches is straining relationships between bishops and those priests who hoped the church would be more compassionate.

“As the cost of living continues to rise in the UK, one in five clergy members sought charitable aid over the last year.”

As the cost of living continues to rise in the UK, one in five clergy members sought charitable aid over the last year. The Clergy Support Trust gave assistance to 5,000 clerics, a new record for the organization.

This angers some in the church who are having trouble making ends meet. The Church of England possesses a £10.3 billion investment fund with a 10.2% rate of return. A growing number of clergy say more of that money should be used to help struggling priests and their parishioners. In response to these frustrations, more and more priests in the UK are joining trade unions.

Unite the Union oversees several different professions, including clergy in its Faith Workers Branch. A survey released by Unite on Oct. 23 reported 75% of its religious members work more hours than they are contracted to work and that a third of those who responded are planning to leave the ministry within the next year or two.

“All religious groups need to take a long hard look at whether they are providing the right conditions and support for their workers. Talking about caring for the poor and needy is one thing. Taking action when their own are in need is another,” Unite regional coordinating officer Sarah Cook said in a statement. “By the time you calculate hours worked, most of these faith workers are, in reality, receiving less than minimum wage. In a society that relies upon faith workers to pick up the slack, the religious bodies they serve so devotedly need to set an example and dramatically improve their conditions.”

“By the time you calculate hours worked, most of these faith workers are, in reality, receiving less than minimum wage.”

In June, members of Unite’s Church of England Employee and Clergy Advocates, known for short as CEECA, submitted an official pay claim asking for an increase of 9.5% in their annual stipend (salary paid to priests by congregations). This would increase the national minimum clergy stipend to £29,340, and the national stipend benchmark paid to incumbent clergy to £31,335. Both figures are used by various diocese to determine the pay of individual priests.

“All clergy should be paid at a level that secures relief from financial hardship, promotes personal well-being, and enables them to effectively serve and support their local communities. The proposed increase is necessary to start bringing pay back in line with inflation while addressing the most urgent hardship and anxiety faced by too many clergy and their families,” said Sam Maginnis, an activist with Unite. The CEECA also is lobbying for a national plan to assure every local diocese can afford to adequately pay their clergy.

Tough sell for Baptists

While union representation might make sense for priests in a large, centralized denomination like the Church of England, it’s more difficult to determine how labor unions would operate within a Baptist context.

“It doesn’t really fit with the culture or the structure of Baptist churches, as the ‘employer’ is the local congregation,” said Martin Hodson, general director of the Baptist Union of Scotland. “There is generally a strong bond of trust between minister and congregation, which would make the idea of joining a union unthinkable.”

“There is generally a strong bond of trust between minister and congregation, which would make the idea of joining a union unthinkable.”

Baptist ministers in the United States face similar structural barriers to unionization. They must contend with the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of religion, including the freedom to select religious leaders.

However, churches and other houses of worship have used this “ministerial exemption” to discriminate against and remove clergy for reasons related to their age, sex or disability. The courts have sided with religious groups over their employees in such cases. Judges also have ruled that faith groups are exempt from providing pension protection, unemployment benefits and permitting employees to form unions. Thus, it is up to churches to do the right thing when it comes to clergy.

Could that include allowing employees to organize a union?

In America, the onus is on workers to organize individual businesses on an “establishment level” rather than industry wide. Perhaps a particularly large church could form a union, just as a few private (autonomous) schools have unionized. However, most churches in the U.S. are quite small and on their own never would achieve the collective bargaining power that gives unions their strength.

It might be possible for pastors to become part of an existing union, such as the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union. While the NPEU currently has no clergy in its ranks, nonprofit workers and clergy have much in common. Both are dedicated to a larger cause and are often reluctant to lobby for their own needs while serving others.

Setting aside the logistics of forming a union, Baptist support for unions in general has wavered considerably. While local churches typically have based their support (or opposition) on the impact of unions in their communities, the Southern Baptist Convention occasionally has made public pronouncements at its annual convention. In 1930, the SBC passed a resolution in support of the labor movement, but that support diminished in every year since. By 1948 the SBC had adopted the more hands-off position of urging workers and management to become “God-fearing Christians,” believing shared salvation would be the key to resolving their differences.

Working conditions

Being “God-fearing Christians” is not enough to protect many clergy from poor working conditions.

The Faith Workers Branch of Unite reports that one third of calls to its hotline number are from clergy who are being bullied by members of their congregations or by supervisors.

“One third of calls to its hotline number are from clergy who are being bullied by members of their congregations or by supervisors.”

Women in ministry, both in the UK and the U.S., regularly endure sexual harassment on the job. Although many female pastors have received training in how to report abuse within the church, there are no protocols when they themselves are the victims. Many are forced to leave their churches or the ministry entirely.

Female clergy also typically are paid less than their male counterparts. While the numbers are unavailable for Baptist pastors, a study conducted by the United Methodist Church showed women made 11% less than men in 2020. This comes a decade after a 2011 study reported UMC Black, Hispanic/Latina, Native American, Asian American and Pacific Island American ministers earned anywhere from 9% to 15% less than white clergy. Very often women and minorities in predominantly white, male denominations are reluctant to ask for equal pay, believing they are fortunate to have a job at all.

In other workplaces, a union presence is known to raise women’s pay and reduce racial disparities in income, not just for union members but for all workers, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Pastors just out of seminary also are likely to encounter difficulties making the transition to full-time ministry. While denominations and pastoral mentors may give some guidance, the newly minted pastor is largely on her own when it comes to negotiating salary and benefits. In this way, Baptist clergy are like independent contractors; but even freelancers now have a union in the U.S. to help them with health insurance, paid leave and unemployment benefits.

Of course, the need for assistance doesn’t end once a pastor assumes the pulpit. In fact, the greatest needs often arise after the search committee disbands and the congregational honeymoon is over. If push comes to shove, pastors who cannot afford a lawyer, or who are unaware of their rights, are on their own unless a sympathetic member steps in to help. Such a scenario is damaging to the pastor, the member and the church, which may splinter as a result of conflict.

Another benefit unions provide is a sense of community and solidarity. Episcopal priest and former union organizer Ben Crosby wrote about his experiences in a post for Yale Divinity School: “The modern economy is one which atomizes and isolates. Our job was to build a workplace culture where we helped each other out, where we were involved in each other’s lives, where we were honest and vulnerable with each other.”

According to Barna, 65% of pastors feel lonely and isolated. They also report feeling less supported by those around them. The autonomy of the Baptist church, while key to the Baptist belief system, also means Baptist clergy often are more isolated than those serving in centralized denominations.

What’s the future?

The local church’s future may depend on some form of unions for its pastors. Workers from Generation Z (those born between 1996 and 2010) are naturally collaborative. They are more interested in joining unions than their predecessors and were largely responsible for unionizing the Buffalo Starbucks that sparked the organizing movement among that corporation’s baristas.

Knowing the economy they’re part of is leaving them worse off than previous generations, members of Generation Z are demanding a better work-life balance and healthier, more flexible work environments. They’re looking to unions to help them achieve these demands.

“If almost half of young pastors are considering leaving the ministry, they will need more than a little mentoring to convince them to stay.”

If almost half of young pastors are considering leaving the ministry, they will need more than a little mentoring to convince them to stay. They will need the kind of community and sense of solidarity that unions provide, as well as the tools and resources they offer.

Given the difficulty of forming a labor union under the American system, and the decentralized nature of the Baptist denomination, establishing a union for Baptist clergy may not be feasible.

There are alternatives, however, that could approximate a union in providing support, insurance, legal representation and other services. Pastors, along with doctors, nurses and teachers — all drawn to their professions by a desire to serve — are now treated more like servers within the service economy.

As the church becomes yet another marketplace where the “customer is always right,” younger clergy in particular believe they should have just as much support and protection in their profession as Starbucks baristas.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.