There are about 2,600 Baptist churches scattered throughout the United Kingdom. The majority (2,000) are in England, where Baptist forebear Thomas Helwys established the first Baptist church on British soil. Another 300 are in Wales, 200 in Scotland, and the remaining 100 are in Northern Ireland.

Most of these churches are small, and while they play an important role in their respective communities, Baptists as a whole cause barely a ripple in British culture, especially when compared to the current that is the Church of England.

Martin Hodson

“In England, there’s a strange stickiness that exists between the establishments in the form of historic institutions and the Church of England,” according to Martin Hodson, general director of the Baptist Union of Scotland. “The Baptist churches are generally much more on the fringe of things and not aligning ourselves with existing institutions in that way.”

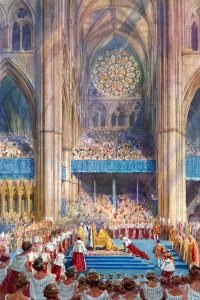

The conjoining of the Church of England and the monarchy of Great Britain was on full display during the recent coronation of Charles III. The United Kingdom is the only European nation still to hold an elaborate coronation for its monarchs rather than a simple inauguration.

“There’s a thing in the DNA of the (Baptist) church here about the importance of the separation of church and state.”

This alignment of religion and government can be quite jarring to Baptists. In the 1600s, “when the Baptists first began in England, it was an illegal movement and the established church tried to suppress it,” Hodson explained. “So, there’s a thing in the DNA of the (Baptist) church here about the importance of the separation of church and state.”

Sixth century roots

To understand why Christianity and coronations go hand in hand in the United Kingdom, it’s necessary to go even further back in time, to the sixth century.

Stained glass depiction of St. Augustine

Long before Britain was united, newly converted Anglo-Saxon kings looked to the church to legitimize their rule. At the same time, the church in Rome sought to align itself with local monarchs to spread its influence along with the gospel. When Saint Augustine, the first archbishop of Canterbury, journeyed to England in AD 597, his first stop was to see the Anglo-Saxon King Aethelbert.

Celtic Christianity already was 300 years old when Augustine arrived but had little interest in organizing itself as a force for political influence. Augustine, as a representative of Pope Gregory in Rome, would change that. With the king’s patronage, Augustine established a school and an abbey just east of Canterbury. He also persuaded Aethelbert to pass laws favorable to the church. This was the beginning of a partnership that continues to influence England even now.

In AD 959, King Edgar I united the warring factions of Anglo-Saxon England and, along with his archbishop of Canterbury, Dunstan, ushered in a new age of Benedictine monasticism in England. The church’s wealth, property and authority grew dramatically during this time. To celebrate the achievements of Edgar’s reign, the church held a formal coronation for him in AD 973 at Bath on the Day of Pentecost.

When planning this English coronation, Dunstan looked to the coronations of continental Europe for inspiration. Borrowing from these rituals, Dunstan anointed the king on his head, hands and heart and presented him with a ring, a sword and a scepter.

A significant musical shift

Edgar in the second tier of the Royal Window in the mid-fifteenth century chapel of All Souls College, Oxford. The stained glass is original apart from Edgar’s head, which was replaced with one made by Clayton and Bell in the 1870s. (Wikipedia)

However, Edgar’s anointing departed from those across the Channel in one significant way. In France, the text for the sung antiphon was Samuel’s anointing of David. For the English coronation, Dunstan chose instead Zadok’s anointing of Solomon in 1 Kings 1:38.

The symbolism of this change is striking. In 1 Kings 2:35, Zadok himself is appointed as sole high priest for his faithfulness to King Solomon, who would later build God’s temple in Jerusalem. The chant thus celebrates the church’s authority as well as the king’s. A musical rendition of the Zadok passage has been sung at every monarch’s coronation ever since, reinforcing the interconnectivity between church and state.

“A musical rendition of the Zadok passage has been sung at every monarch’s coronation ever since.”

Handel’s famous arrangement, composed for the coronation of King George II in 1727, and performed at the coronation of King Charles III, continued rather than originated this tradition.

What happened in 1066?

William the Conqueror’s invasion of England in 1066 cemented the symbiotic relationship between royal power and ecclesiastical authority. William, who was Duke of Normandy, claimed Britain’s King Edward the Confessor had chosen him as his successor. However, the nobles of the Witan and the archbishop of York had anointed a rival claimant, Harold Godwinson.

Even though William would defeat Harold at the Battle of Hastings, his kingship was not assured. King Edward had another heir lurking about, and the northern earldoms teetered on rebellion. William looked to the church to establish his legitimacy.

During his Christmas coronation at Westminster Abbey, the Norman William leaned heavily on the religious traditions inherited from Edgar’s coronation to lend a sense of continuity to his reign. He gave the holy unction a prominent place in the coronation. No longer was it just another symbol of kingship. For William and his descendants, the anointing sacramentally transformed a man into an extension of God.

“The rest of us, the hoi polloi, the peasants like us, have to accept him as king because it’s clearly God’s will and he’s anointed by God’s representative the archbishop to fulfill that role,” Hodson explained. “The anointing in some people’s theology may be welcome, but it seems to me in danger of being quite manipulative, or it has (been) in the past, in a more Christianized country. It’s a way of putting the king above criticism.”

Enter Henry VIII

The church served the monarchy again in the 16th century when King Henry VIII sought a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. The Protestant Reformation already was under way in Germany and the Netherlands. Henry himself had authored a pamphlet refuting Martin Luther’s complaint against the Catholic church in 1517 and was given the title “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X for his efforts.

16th century ruins of Valle Crucis Abbey, Llangollen, Wales, closed by order of Henry VIII.

However, when Pope Clement VII refused to grant his divorce, Henry broke with Rome and turned to Protestantism. “Whereas Henry VIII brought about the English Reformation, in Scotland we inherited the Presbyterian model from the European mainland via Calvinism and John Knox. Which was not a system that was ever going to have a king or queen as the head of the church,” Hodson said.

With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Parliament made Henry VIII the supreme head of the Church of England.

“What will blow your mind,” said Graham Smith, who was a Baptist for many years before returning to the Church of England and pursuing the priesthood, “is that prior to being ordained in the church of England, candidates are required to swear an oath which contains, ‘I do solemnly, sincerely and truly declare and affirm that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to His Majesty King Charles III, his heirs and successors according to law.’”

‘Defender of the Faith’

Henry VIII also kept the title “Defender of the Faith.” King Charles III, like British monarchs before him, inherits both titles; however, he sees a changed role for himself in the 21st century: not just defending Christianity but also protecting the freedom to worship for all his subjects.

“From a Baptist perspective, this is entirely correct, though with the qualification that this should be the duty of all agents of the state, royal or otherwise,” wrote Nigel G. Wright, former president of the Baptist Union of Great Britain. “Religious freedom is the cornerstone of all our freedoms.”

“Religious freedom is the cornerstone of all our freedoms.”

To reflect the king’s views, a new paragraph was inserted before the traditional oath in the coronation liturgy. In it, Charles promises to “foster an environment in which people of all faiths and beliefs may live freely.” As part of the coronation investiture, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Sikh members of the peerage presented the robe, armills, ring and glove to King Charles. Then, during the outward procession, representatives of non-Christian faiths greeted the king with a declaration on the importance of public service.

Hodson explained: “Making it more inclusive in this way is a way of avoiding the other pressure, which is to make it more secular, because there are plenty of voices saying, ‘Why on earth is this such a religious process when most of the country’s not religious? Why is this a Christian process when most of the country’s not Christian?’”

Graham Smith of Bracebridge Heath, England, is glad to see the new additions. “The last 25 years has seen a huge expansion in people of other religions migrating to our country, bringing their religion and culture with them. I am therefore pleased the king has indicated his desire to have representatives of other faiths also paying homage at his coronation.”

More ecumenical coronation

Coronation organizers from the Church of England took steps to make the event more ecumenical as well.

“There’s a sense in which the Church of England is being magnanimous to its smaller brethren and saying, ‘In this day and age we want a more inclusive model’,” Hodson said. “It was probably important for Scotland that the moderator of the Church of Scotland had a significant part in the service and presented the Bible to the king and said some good Protestant words about the importance of Scripture.”

Julie Siddiqi, Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis and the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby help sort clothing as they join other faith leaders in taking part in the Big Help Out, at the Passage in London, which aims to inspire and recruit a new generation of volunteers by showing how easy it is to get involved. The event with faith leaders and activists from the Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities is to encourage people to take part in The Big Help Out volunteering project on May 8, as part of the weekend of celebrations for the coronation. Picture date: Wednesday April 19, 2023. (Press Association via AP Images)

While the king is the head of the Church of England, he is considered only a member of the Church of Scotland, which recognizes Jesus Christ alone as “king and head of the church.”

The United Kingdom has not always existed so ecumenically. King James I juggled a divided Church of Scotland, Catholics trying to kill him, Puritans in the Church of England denouncing him, and dissenters like General Baptist Thomas Helwys denying any spiritual dimension to his royal authority. Helwys famously penned a note to James that read, “The king is a mortal man, and not God, therefore he hath no power over the mortal soul of his subjects to make laws and ordinances for them and to set spiritual lords over them.”

Thomas Helwys

King James I confined Helwys and his Baptist followers to Newgate Prison for their beliefs, and there Helwys died in 1616.

“It should be remembered that the Baptist martyr Helwys was equally emphatic about loyalty to king and nation in their proper sphere, the maintenance of peace and order,” Wright said. “He denied the legitimacy of the king in dictating religious conformity but implicitly saw that there could be a vital role in securing religious freedom.”

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion would be a long time coming in England after the death of James I. Civil war erupted during the reign of his son, King Charles I, when the king, believing in his God-given right to rule, clashed with Parliament. Interwoven with the political turmoil were religious conflicts among Catholics, Puritans and the Church of England.

“The divine right of kings ceased when Charles I was beheaded,” Smith said. “We then went through a few turbulent years as a republic.” The English Civil War and continuing conflict that followed would heavily influence the future relationship between the church and the state.

“We had a commonwealth with no monarch after the English Civil War, and decided we didn’t like it, so we brought the monarchy back,” said Barbara Doye of Weathamstead, England. Many of the objects used in coronation of Charles III, including the Crown of Saint Edward, were made for Charles II in 1661 to replace regalia lost during the interregnum. When James II, who was Catholic, succeeded his brother Charles II as king, it touched off a mass panic. Parliament and Protestants, among them the Church of England, feared a Catholic king might become a puppet of Catholic superpower France. James II was deposed and replaced by his Protestant daughter, Mary, and her Dutch husband, William.

George VI receiving the homage after being crowned in 1937; watercolour by Henry Charles Brewer (Wikipedia)

The couple was crowned jointly in 1689, but there were strings attached. William and Mary agreed to a Declaration of Rights (later a Bill) granting Parliament the sole authority for legislation, taxes, the military, and ensuring free speech along with fair courts.

“The monarch doesn’t have executive powers like the president in the States. The understanding is that political power is in the hands of the elected politicians,” Hodson explained.

With its powers much curtailed, the monarchy resembled the constitutional monarchy that exists in the United Kingdom today. Most of the modern monarch’s responsibilities are symbolic or ceremonial.

“Monarchy has taken a shift similar in nature to the Church of England. Charles III is not Charles I. Monarchy has shifted from the abuse of power to a vocation to service, from divine right to public consent,” Wright said.

Public service?

The royal family’s website explains the sovereign “is a focus for national identity, unity and pride,” provides a “sense of stability” and “supports voluntary service.”

Smith believes King Charles III excels in all of these roles: “He serves by his presence and through the ways he honors tradition. The king is a figurehead that we can all look up to and admire.”

Other residents in the UK aren’t so sure. “Whether you can be a servant when you’re so loaded with wealth and prestige all the time is an open question to me,” Hodson said.

A recent poll conducted by the BBC television show “Panorama” found 58% of all respondents preferred the monarchy to an elected head of state. However, that sentiment rose and fell across age brackets: 78% of those over 65 said they supported the monarchy, while only 32% of those 18 to 24 were in favor of keeping it. Most residents felt they were getting “good value” for the monarchy, although almost a third disagreed.

Edward VII taking the oath in 1902 (Wikipedia)

And even those who are pro-monarchy have concerns about the cost of the coronation. At an estimated £250 million, the coronation of King Charles III will cost more than twice that of his mother Queen Elizabeth II. Another survey of Britons on the website YouGov showed 51% thought taxpayer money shouldn’t be paying for the king’s coronation, especially when the nation is suffering a cost-of-living crisis resulting from record inflation, surging energy prices and stagnant economic growth.

King Charles himself is worth an estimated £1.8 billion and takes full advantage of the many tax loopholes Parliament has allowed for the royal family. If Charles had been obligated to pay taxes on his inheritance from Queen Elizabeth, the amount would have covered a sizable portion of his coronation’s cost, if not the entire undertaking.

“The very concept of monarchy, of someone so hideously rich being dealt with such lavish ceremony, is a challenge to any movement that believes in the gospel for the poor or giving preference to the poor,” Hodson said.

Monarchy and Christianity both in decline

If the monarchy’s popularity numbers aren’t where they were at the time of Elizabeth II’s coronation, neither are Christianity’s. The last UK census for England and Wales reported only 46% of the population referred to themselves as Christian. (COVID has delayed the reporting of Scotland’s census results).

Not since King Edgar’s coronation in the 10th century has the percentage of practicing Christians been so low in Britain. “When we’re living in a post-Christian era, it is a little bit anachronistic for this to be a national ceremony that assumes we are a Christian country when only 5% of people, perhaps, are worshipping in a church on a Sunday,” Hodson lamented.

Such dissonance could prove problematic for a nation whose governance is so closely woven with the Church of England. A recent decision to allow blessings but not marriage for same-sex couples in the Church of England put the denomination at odds with much of the UK’s population. Church of England bishops and archbishops hold 26 seats in the House of Lords, in accordance with the nation’s constitution. This could cause a constitutional crisis should any LGBTQ issues come before Parliament.

Calls for disestablishment

With Christianity now a minority religion, some are calling for disestablishment, even from within the church.

“The aspect of Anglicanism that I find hardest to deal with are the more ‘establishment’ occasions, such as royal events,” said Doye, who was raised Methodist but is now a lay minister in the Anglican church. “It’s the unspoken assumption that everyone present holds the same views and that these views are the ones being endorsed by the established church.”

“It’s the unspoken assumption that everyone present holds the same views and that these views are the ones being endorsed by the established church.”

The archbishops of Canterbury and York, however, remain optimistic. They believe the coronation is an opportunity to “receive from Jesus” and presents a “unique missional opportunity for the church.”

With both the church and the monarchy facing future decline, it remains to be seen if the king’s coronation can reverse the trend.

Nigel Wright

For Baptists in the United Kingdom who believe in the separation of church and state, the coronation of King Charles III presents a unique challenge. “How do Baptists respond to this? I suspect our churches have now become a ‘mixed multitude’ composed of people from a variety of church backgrounds, many of whom have no great understanding of the political significance of Baptist doctrine,” Wright said.

Some Baptist churches participated in a nationwide day of service on May 8. Others distributed an evangelical resource based on the Gospel of Matthew.

In Scotland, the mood was a bit more subdued.

“The Baptist Union of Scotland, although we’ve invited people to pray for the king, we’ve not encouraged special celebrations around this because the feelings are quite mixed around the country,” Hodson said. “What people have picked up on is the theme of servanthood that was evident in the coronation service because it began with the reference to Mark 10:45, the ‘not to be served but to serve.’ That seems to have caught the imagination of churches … as a proper description of Jesus as the King of Kings and as a model for our own discipleship.”

While the future of the monarchy and the preeminence of the Church of England are in doubt, Martin Hodson thinks the future for Baptists in the United Kingdom is looking bright precisely because they aren’t at the center of society.

“We’ve got the dynamic of being local congregations responding to the leading of the Spirit, the opportunities for the gospel, the opportunities to serve the poor … without the trappings or the pressure of some kind of institutional belonging,” Hodson said. “There aren’t people in Baptist churches saying, ‘We should be represented at the coronation.’ It’s not why we exist in society; we definitely exist on the edge. We’re at our best on the margins.”

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.

Related articles:

King Charles should abolish the term ‘Defender of the Faith’ | Opinion by Michael P.L. Friday

Defender of the Faith or Defender of Faith — a distinction informed by Baptist history | Opinion by Jerrod Hugenot