Eighth grade social studies class in North Carolina, in my school years, covered the history, geography and economy of our fair state. Mrs. Spivey was my very fine instructor, and I am confident she would confirm that I was an equally fine student. The year was 1992. The spring held a Duke basketball championship, the fall a presidential election. I was paying close attention to both.

I was a careful student in my lessons, and not just because I wanted a perfect report card, although I did. I cared about the stories, the history of being “Tar Heel born and Tar Heel bred.” I cared about the politics, the decisions adults were making around me, the way my conscience was waking up to the connections between my Sunday School lessons and the school bus route, between the behavior I observed behind the curtain of the voting booth in November and in the public realm displayed on town streets and in newspapers.

I was a careful student in my lessons, and not just because I wanted a perfect report card, although I did. I cared about the stories, the history of being “Tar Heel born and Tar Heel bred.” I cared about the politics, the decisions adults were making around me, the way my conscience was waking up to the connections between my Sunday School lessons and the school bus route, between the behavior I observed behind the curtain of the voting booth in November and in the public realm displayed on town streets and in newspapers.

I had picked up on a few inconsistencies already. For one, Jesse Helms was a racist, but that was the price white North Carolinians had to pay to have Jesse Helms as their senator, and at least he was honest about it. I probably figured that the moral shortcomings were forgivable in light of the noble history of our state. First to declare independence, first in flight. We were on a path, our state motto told us, “to be rather than to seem.” Our “valley of humility” existed between two “mountains of conceit,” aristocratic South Carolina and elitist Virginia. The Old North State was home, and nothing could be finer.

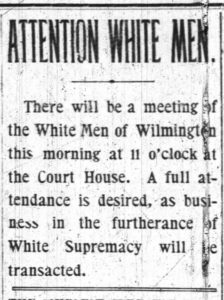

Announcement in the Wilmington Messenger on November 9, 1898. (Public domain)

Some of the history, I’ve come to learn, did not make it into the curriculum. Over the years, the official holders of the stories began filtering out some of what our teachers taught us, and how. Teaching the lies of The Lost Cause, in part if not in whole, was one mistake. But beside the commissions were the omissions, the things elided or glossed over or left out altogether.

Perhaps the most notable of those events that never made it to the curriculum was the story of the race massacre in Wilmington in November 1898. Wilmington was then the state’s largest city. Like many other towns around the state, the four years preceding the election of 1898 had seen an economic alliance between Black people and poor white people. During those hope-filled moments, these allies voted together in large numbers. They won elections and re-wrote many of the state’s laws to create a framework that looked more like justice and equity. The alliance was uneasy, never fully realized, but it worked.

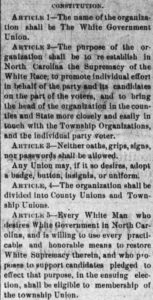

As fall 1898 approached, powerful white men began using racism to drive a wedge between Black people and poor whites. Poor whites chose to believe they were white rather than to choose their economic interest. Over the course of several months, newspapers, vigilante groups, politicians, ministers and businessmen stirred the flames of hatred. When election day arrived, they blocked access to the ballot box and threatened violence, effectively overthrowing the democratic process.

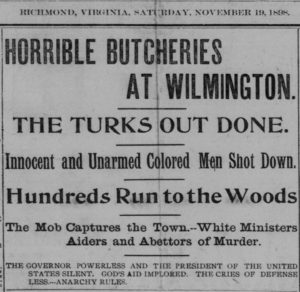

Not satisfied with their cheap victory, two days later, a massacre began. White vigilantes took to the streets, and over the course of the day killed dozens of Black people. Black families ran for safety to swamps and cemeteries on the edge of the city. When white terrorists did not murder key Black leaders, they ran them out of town. By the end of the day, a multi-racial government in a thriving city was deposed, the only successful coup in the history of the republic. No person associated with the massacre ever faced consequences for their actions.

Headline from the Richmond Planet on Nov. 9, 1898. (Public domain)

Two recent sources have recounted this story well. The documentary Wilmington on Fire tells the story in film, and the book Wilmington’s Lie by David Zucchino narrates the context, the events and the aftermath in full detail. Prior to these recent contributions, this story of a deadly white supremacy campaign waged in North Carolina was little known, except to a few historians and to the Black community in Wilmington who kept the memories of their ancestors alive. Although it was central to our state’s history, it was certainly not taught in eighth grade history during the 1990s. (The newest curricula correct that mistake, however.)

It would be a mistake to think that the events in Wilmington 120 years ago are not still with us. The stories of history do not disappear simply because only a few people know them. What people forget, institutions remember.

So it has been in North Carolina since 1898 and the violent repression of multi-racial democracy here. The story of Wilmington was ignored, or watered down, or called a “race riot” rather than a massacre and coup d’état, for generations. What people forgot, the people’s institutions kept enacting. They did so — we did so — through police agencies, churches, school systems, real estate practices, lending institutions and the whole set of systems that constitute a way of life.

Policies mostly did our oppression for us; white people were freed to go about their racism in pleasant, colorblind ways, fitting to the genteel South, except in a few instances. We assumed occasional acts of racial terrorism were exceptional, not central to our story, and certainly not enshrined in our monuments, or neighborhoods, or schools, or governance. Offensive acts of overt racism served to reinforce our sense of moral goodness, to further trap us into a history, as Baldwin writes, that we could not understand, and thus could not be released from.

White Government Union Constitution published in the Wilmington Morning Star, 1898. (Public domain)

Forgetting is no way to raise children who are capable of maturity. The only way to achieve maturity is to reckon with hard things, things we would rather forget, things that will challenge white identity, built as it is on falsehood and half-remembrance. This is why tearing down statues matters — not because statues are deep, institutional change, but because the empty pedestals offer a chance to confront the emptiness of the moral narratives that have guided us. They offer a chance to construct a new story. Perhaps a redeemed one.

Christians have as a central practice the sharing of a meal instituted by these words: “Do this in remembrance of me.” The immediate response to a body broken is not to vainly try to put it back together. It is to remember the story of its brokenness. Healing, that practice suggests, comes from remembering, in fullness and in truth, around common tables. It comes from telling the whole story and from accounting for the damage that failing to tell the whole story has done to our souls.

From a people committed to forgetfulness will spring institutions that do our remembering — and our sinning — for us. To remember, though, makes possible the beginnings of repair — of institutions and churches and families that might finally be part of healing ourselves and our land.

Greg Jarrell spends his days playing, working and conspiring with the family of disciples at QC Family Tree in Charlotte, N.C. His latest book is A Riff of Love: Notes on Community and Belonging.