“Borrowing” someone else’s sermon is one of the top four ways pastors get fired from churches, according to Thom Rainer, former president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s publishing arm and a noted interpreter of modern Christianity.

Rainer made that statement four years ago in a website post titled “The Four Most Common Acts of Stupidity that Get Pastors Fired.” He included sermon plagiarism along with flirting dangerously with sexual boundaries, financial stupidity and social media madness.

His assessment explains, in part, why such a furor has arisen over accusations that newly elected SBC President Ed Litton has copied some sermons from his predecessor, J.D. Greear. The accusations and responses are flooding social media, especially on Twitter, among SBC leaders.

Whether Litton is guilty as charged or not, and whether he should resign his post (as some are demanding) or not, the current situation draws attention to an age-old and highly controversial reality: Some pastors don’t write their own sermons.

The current situation draws attention to an age-old and highly controversial reality: Some pastors don’t write their own sermons.

That fact was easier to hide before the birth of the internet and the common practice of churches of all sizes posting their worship services and sermons online through platforms such as YouTube or Vimeo.

However, well before the internet, preachers had access to entire books of sermon manuscripts by notable pastors and even subscriptions to weekly or monthly publications full of sample sermons. No matter how clearly these resources were touted as being merely for inspiration or illustration, they ended up for some pastors being the source of entire sermons delivered nearly word-for-word as someone else had first preached them.

Thus, it was not uncommon for congregants to tune in to hear radio and TV preachers like Adrian Rogers or Charles Stanley on reruns and suspect those giants had borrowed from their own pastors — because they knew they had heard this before. The problem was, the borrowing always went the other direction.

Preaching is hard work

“The weekly preparation of a sermon is arguably one of the most difficult and demanding ministerial tasks. Each week you’re expected to deliver a sermon that is insightful, inspirational, relevant, and, truth be told, brilliant,” said David Ramsey, who served 10 years as pastor of congregations in Virginia and today is a businessman and author.

David Ramsey

Invoking a baseball metaphor, the graduate of Duke Divinity School and Princeton Theological Seminary said congregational expectations are that the preacher will “hit it out of the park, Sunday in and Sunday out.”

That, he said, is “a daunting, if not impossible, exercise. There is an old saw in clergy circles that goes something like this: Some Sundays you have something to say, and some Sundays you have to say something. And Sunday seemed to come faster and faster every week.”

Plagiarism versus inspiration

Amid such performance pressures, just where is the line between drawing inspiration from another preacher’s sermon and plagiarizing it?

Hayden Hefner

Hayden Hefner, a master of divinity student at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, wrote about this for The Gospel Coalition, a conservative evangelical group that adheres to Reformed (Calvinistic) principles and highly values preaching as craft and ministry.

He defined pastoral plagiarism as “preaching (or writing) someone else’s unique ideas (outlines, insights, examples) in such a way that causes the congregation to believe those ideas originated from the preacher.”

This means pastors who plagiarize sermons are guilty of a double sin, Hefner wrote: theft and deception. “When a preacher plagiarizes, he is not merely making an ‘unwise decision’ or engaging in ‘immature indiscretion.’ He is violating both the eighth and ninth commandments (Exodus 20:15–16). He is insulting a true and holy God.”

Preaching professors agree

For those who have dedicated their lives to teaching the craft of preaching, there are few more grievous sins than plagiarism.

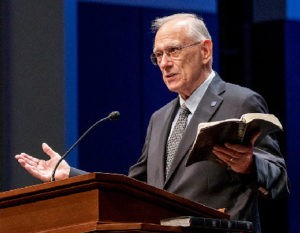

“Sermon plagiarism is an insult to God,” said Al Fasol, distinguished professor of preaching emeritus at Southwestern Seminary. “The plagiarizing preacher essentially says to God, ‘You made a mistake in calling me because I cannot prepare a sermon, nor can you inspire me to prepare one.’”

Al Fasol

Likewise, pastors who excuse their plagiarism by saying they don’t have time to prepare a good sermon insult God, Fasol added. “The pastor is essentially saying, ‘You called me to preach, but I have chosen other priorities.’”

There is a difference between consulting the sermons of others (“not a bad thing”) and copying the sermons of others, he said. “When reading another’s sermons, we may gain insights as to how to interpret a specific biblical text. Preachers who are ‘inspired’ or ‘influenced’ by the sermons of others will use similar words as they exposit a specific text, but the application and illustrations in the sermon must be the preacher’s own words as the preacher feels led of God to prepare the sermon.”

The voice of experience

George Mason not only is one of the best-known preachers within the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, but he has personally mentored nearly three dozen young pastors through his Dallas congregation’s pastoral residency program. At Wilshire Baptist Church, young seminary-trained pastors are hired for two-year intensive practicums that include weekly homiletics seminars and group feedback on every sermon preached.

George Mason

In that environment, all the church’s preachers, including Mason, may draw inspiration from group conservation and the sharing of resources.

“All of us share a calling to a common work,” he explained. “We should be eager to help one another and to share our work.”

But there are limitations to appropriate sharing, he added. “When a story is being retold, the source should be mentioned or at least cited in a manuscript note. In no case should preachers retell a story as if it is their own, especially not as if it happened to them when it did not. If sermons are littered with citations from other people’s work, it ought to cause those preachers to rethink their vocation.”

And about those paid subscription sites for ready-made sermons? “If a preacher publishes a sermon on a sermon resource site that another pastor has paid to subscribe to, there is an expectation that, like commentaries, the sermon material is fair game to use. Even then, it’s better to use it as a resource for insights and illustrations than for whole sermons,” Mason said.

Community with boundaries

A sense of community in preaching is important to Anne Scalfaro, senior pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Denver, who calls preaching a “shared vocation.”

Anne Scalfaro

That means she welcomes other preachers to utilize her sermons for inspiration and content, just as she may find inspiration and content in their sermons. “The ethics of preaching means I always reference or footnote sources, and I would expect others to do the same with my material, less for the sake of credit and more for the sake of witnessing that the living word and Spirit does not speak in isolation but rather in community.”

Lifting someone else’s sermon out of it time and context is not really preaching, Scalfaro said, “for preaching requires a discerning spiritual practice — of which blatant plagiarism is not.”

She recognizes the time demands on all pastors and understands the temptation toward plagiarism as a temporary relief to get through another Sunday. “However, it seems to me that if one is so pressed for time that they cannot write their own sermon, or if they are feeling stressed and uninspired and with little to no reserves, the most honest thing the preacher can do is tell her congregation that and invite another preacher into the pulpit that week (or for many weeks) and allow God to speak and inspire through one of the many voices in ministry that is longing to have a pulpit from which they can proclaim.”

Pastors and congregations should see their shared ministry as a “sprint, not a marathon,” she added. “The myth of the preacher having something new and profound to say each and every week keeps us from the blessing of a shared pulpit or even from the blessing of a service of worship without a spoken sermon, but where music or silence or art or testimony is the Word made flesh.”

Ways to see the danger zone

Jake Hall serves as pastor of Highland Hills Baptist Church in Macon, Ga., where his congregation includes both academics and community leaders. He offered several ways for pastors to know when they are crossing from acceptable to unacceptable inspiration from the works of others:

Jake Hall

- “Participating in the chorus of preachers commenting on a common text is very different than lip syncing another artist’s solo.”

- “Mining a nugget of gold from a vein of an extant sermon is different than stealing the deed to the mine and hastily scribbling your name.”

- “The crime isn’t really even plagiarism but the unreported homicide of the preacher’s homiletical imagination.”

- “Preaching someone else’s sermon wholly crafted for another encounter in a different place casts the preacher and congregation in the strangest of fantasies. The preacher engages in a temporarily satisfying role-play while leading an unknowing congregation into accidental voyeurism.”

- “We all rely on each other in this work. You can legitimately borrow your neighbor’s tools of art to create; after all, a brush bears no copyright. But you can’t steal their painted canvas and call it your own.”

How to stay out of trouble

Joel Gregory, professor of preaching at Baylor University’s Truett Seminary and arguably one of the best-known Baptist preachers of the late 20th century, offered some basic principles on how preachers can avoid confusion and stay out of trouble.

Joel Gregory

First, he said, “no congregation wants a sermon that is footnoted like a research paper. You do not need to attribute reference works that you use for exegesis to prepare your message. … Those works are scholarly tools that function somewhat like dictionaries or other reference works. If an exegete, however, supplied you with the big idea or focus statement of the sermon, you would do well to attribute that.”

Second, “if you tell a narrative anecdote that you discovered from reading you should give the general source.” For example, the preacher might say, “The New Yorker last week said … .”

Third, “if your sermon story, illustration of lived experience, came from another preacher you must attribute that story to that preacher at the beginning of the story: ‘Alistair Begg told his church in Cleveland … .’”

Fourth, “if the outline, movements, structure or shape of your sermon came from another preacher, you need to say, ‘I was helped in understanding the shape of this text from the immortal Alexander MacLaren … .’”

Fifth, “if you use a sermon title from another preacher you need to attribute that early in the sermon: ‘My sermon title, “Seconding the Motion,” came to me from the late John R. Claypool.’”

And finally, “if you have any doubt about whether or not to attribute, err on the side of attribution. When in doubt, attribute.”

Related articles:

Could newly elected SBC president be forced to resign over sermon plagiarism?

So, what about preaching and plagiarism? | Opinion by Marv Knox

High demands, easy access tempt pastors to plagiarize sermons