When people think about and discuss race, they often fail to see and acknowledge whiteness, distorting the image of God stamped upon all people, Erica Whitaker told participants in a Baptist News Global education conference on hidden racism in Colonial America and its implications for today.

Whitaker, associate director of the Institute for Black Church Studies at Baptist Seminary of Kentucky, discussed “whiteness unseen” in the final session of the BNG event. Participants spent three days examining often-overlooked and typically unacknowledged evidence of racism at Colonial Williamsburg and Richmond, Va.

Erica Whitaker

“My research considers how the powers of ‘whiteness’ function in relation to meaning-making and how the powers of ‘whiteness’ might be reformed … within church worship settings,” Whitaker noted. She is writing a dissertation on whiteness as she completes a doctor of philosophy degree at the International Baptist Study Center at the Free University of Amsterdam.

Coming to grips with whiteness begins with recognizing that seeing involves collaboration between the eye, which receives external information, and the mind, which processes it internally, she said. How people make meaning out of images they see “impacts how we live, behave and organize the world around us — how whiteness is seen or unseen,” she added.

Often, the mind overrides the eye as it interprets images, skewing how people see the world, Whitaker said. Consequently, people can look at the same object but see quite different things.

For example, she reminded participants of vacant spaces they visited the previous day on Richmond’s Monument Avenue. Until recently, enormous statues of Confederate Civil War generals occupied those spaces. Those statue-images evoked entirely different feelings in many white Southerners, who still revere the Confederacy, and in Blacks, whose ancestors were enslaved in the South.

“Ideology, the lens over our gaze, is shaped by our past embodied experience and shapes our current lived experience,” she said. “Ideology distorts images both externally and internally, creating a blurry vision or blindness of current reality — two dimensions of ‘not seeing.’” Beyond that, people often are oblivious to images all around them, emotionally and spiritually unable or unwilling to “see” people and objects and concepts that could shape how they perceive the world.

An important distortion of seeing/unseeing — particularly as it affects how people relate to each other — is the idea that white is colorless, Whitaker said, noting this is “an interesting definition of the word ‘white,’ used to label the color of a large majority of people in the United States.”

White is often considered the opposite of black, even though no other colors have opposites.”

“But if white is without color, then this creates further confusion when compared to other colors, such as black. White is often considered the opposite of black, even though no other colors have opposites.”

Alongside that contradiction, people often associate white with lightness and black with darkness, she said. Those correlations then expand to associate white with right and virtue, while associating their opposites, wrong and vice, with black.

This tendency produces cultural consequences, she stressed. “Because white is associated with a race and a virtue, white people are recognized by virtue of color. Although white is not an actual skin color, there is a virtuous nature of being labeled as white.”

“Although white is not an actual skin color, there is a virtuous nature of being labeled as white.”

Scientifically, “while white is a color, it is not genetically or biologically a race,” but white still is used as a cultural or racial marker or definition, Whitaker reported.

Nevertheless, “today, white people do not want to talk about race,” she observed, noting whiteness is “unseen by design.”

“The term ‘color blindness’ — metaphorically deployed — is a phrase that emphasizes the appeal of whiteness as unseen by white people who would prefer society to have no color,” she said. This “invisibility of whiteness to white people” gives them permission to believe “the lie that white people feel the same as non-white people, as though there were no difference.”

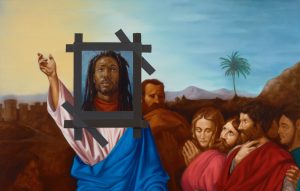

But differences do exist, and they have been expanded and extended by art that reinforces the idea that Jesus was white, Whitaker said.

“Jesus Noir,” by Titus Kaphar, 2020.

Artists began depicting Jesus with light skin during the Renaissance, when painters started using a broad range of colors and tones to present human flesh, she reported. They painted both Jesus and Mary — who often glowed — and Christians in light tones, while depicting John the Baptist and his mother, Elizabeth, with darker tones, even though they also were Jewish and of the same family as Mary and Jesus.

Similarly, during the Crusades, Renaissance artists depicted non-Christians as dark and Christians as light in order to distinguish between the groups and, theologically, to indicate salvation, she said.

Not coincidentally, the Oxford English Dictionary associated the word “bedeviled” with the word “black,” she noted.

“Whiteness is rooted in absolutes that correlate skin color with good or bad,” she said. “The visualization of color on skin and ethnicity created a binary interpretation of white and black. … Badness and blackness became the racial counter to goodness and whiteness. The idea of goodness became coordinated with whiteness.”

“The idea of goodness became coordinated with whiteness.”

“The racialization of skin color (such as depictions of white Christians and dark Muslims during the Crusades) is clearly connected to ‘seeing’ who is saved and who is unsaved and, taking it one step further, who is classified as accepted and who is unaccepted in society,” she explained.

However, the projection of whiteness as virtuous, pure and worthy of salvation sets “an unrealistic standard of not only body but of spirit,” she said. “To be pure white physically is impossible. To be ‘white as snow’ spiritually is impossible. … The unattainable nature of whiteness requires complete absence, to be nothing. The nothingness of whiteness is essentially death.”

While seeing and recognizing whiteness creates discomfort, it also provides vision “to see our way through, not around” the spiritual and cultural discord of racism, Whitaker said. But the alternative is dire. Failure to do so “distorts the Imago Dei — how we see God in others,” she warned.

Related articles: