I sometimes tell the story about how back during the pandemic, at the height of the Black Lives Matter marches, my friend Kelly Brown Douglas schooled me on racial reconciliation. That’s the sort of thing she does.

Until then, I had thought it was enough to engage with white folks about their prejudice and to be a strong supporter, a “white ally.” But she told me in an afternoon phone call that allyship, important as that might be as part of the journey, wasn’t sufficient to cast down white supremacy.

“I didn’t create this problem, Greg,” she said, with her usual frankness. “You did. And only you and people like you can fix it.”

That phone call was a Road to Damascus moment for me. I’d been writing, teaching and preaching about race for years, but in Kelly’s challenge, I sensed a truer call for people who look like me to do more. To be better. And so while I’ve continued in conversation with her and with others who are daily and directly affected by racism and caste, I’ve also leaned hard into finding white allies and fellow travelers who can speak about their journeys and offer their suggestions for repair. (Watch for my interview with Robert P. Jones, one of those essential voices, in this space shortly).

Frederick Allen

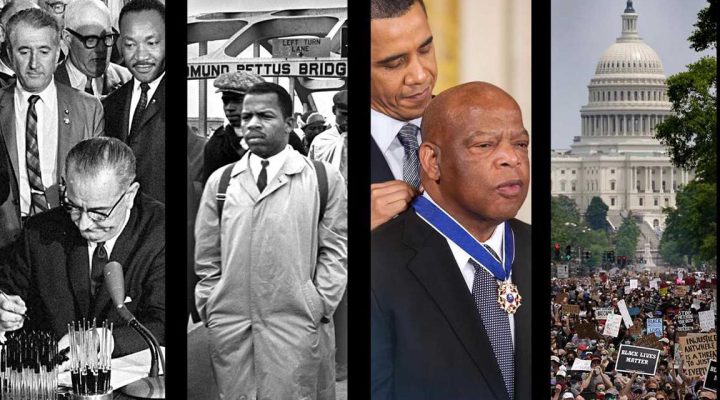

One of those white writers seeking a better understanding of racism and how white people might respond to it is the journalist Frederick Allen. In his new book Reckoning with Race: An Unfinished Journey, Rick looks back across 50 years of journalism — his work with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and as chief political analyst at CNN — and reflects on his own journey from white privilege to greater awareness. Reckoning with Race is an engaging book full of historic figures and important moments but, as he says in our interview, it’s also a record of his greater recognition of the virulence of white supremacy, and his own acceptance of the idea of reparations. I’m grateful to Rick Allen for this conversation.

Greg Garrett: Early in the book, you recall how Eleanor Roosevelt said some of her best friends were Black, something that at the time was both well-intentioned and progressive but now lands with a thud. What other “progressive” ways of thinking about race do you now understand to be clunky and offensive?

“I’m embarrassed that I used to urge my Black colleagues to assimilate into the larger society as if they were a wave of immigrants.”

Frederick Allen: I’m not sure “clunky” is the right word, but the change in thinking about race that I consider the most dramatic of the half-century I’ve been studying the subject is the rejection of “colorblind” as a standard we should strive to adopt in race relations. I’m embarrassed that I used to urge my Black colleagues to assimilate into the larger society as if they were a wave of immigrants.

It took me a lot longer than it should have to see that being Black in America is not a matter of skin color but of culture and life experience. My small crusade is for white folks to try to empathize with Black people and to recognize that Black people confront continuing burdens that we do not.

GG: I understand Reckoning with Race to be written primarily for people who look like us. When you conceived of the book, what did you want us to understand? Is there anything you hoped readers of color might take away from it?

FA: I would be delighted to have as many Black readers as possible, with the proviso that there obviously isn’t much I can tell them that’s new about race in America. But my firm conviction is that race relations are never going to make it to higher ground without the participation of white people.

If I have a sermon, it’s that white people of good will who genuinely desire improved race relations should be encouraged, not chided, if they fall short of a standard of anti-racism I find too harsh.

“White people of good will who genuinely desire improved race relations should be encouraged, not chided, if they fall short of a standard of anti-racism I find too harsh.”

My biggest surprise in responses to my book, by the way, has been the discovery of a dividing line that’s generational more than racial — that is, the older the reader, Black or white, the more likely he or she is to appreciate what I have to say. Younger folks, both races, feel I should have come further in my thinking. I was surprised by this but perhaps should not have been.

GG: Reckoning with Race is based on what you describe as your own flawed story, an unfinished journey from privilege to greater understanding. Admittedly, the whole book is your recreation of that journey, but could you pick three or four rest stops — or battlegrounds — you’d say have been most meaningful to you along your path? Why?

FA: My turning points include, among other things, the realization that white supremacy suffused the country I grew up in, without my even recognizing it. I was born six years before Brown v. Board of Education, when segregation was the law of the land by fiat of the U.S. Supreme Court.

FA: My turning points include, among other things, the realization that white supremacy suffused the country I grew up in, without my even recognizing it. I was born six years before Brown v. Board of Education, when segregation was the law of the land by fiat of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Another insight I gained too late was that my education at the University of North Carolina was not as liberal or as thorough as I imagined at the time. I was a sixties “liberal” who didn’t really understand race at all. In 1972, when I went to work at the Atlanta Constitution, I figured I had already missed the Civil Rights movement, but then I realized I had arrived just in time for the advent of Black political power. I covered the election of Atlanta’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, and watched with fascination his battle to bring change to City Hall.

I like to tell the story of a cable news anchor I heard a couple of years ago reciting a list of injuries inflicted on Black people over the years — redlining, the exclusion of domestic and agricultural workers from Social Security, the difficulties of Black veterans to get the benefits of the GI Bill, environmental racism, the criminalization of poverty, uneven health care — and she said, “I’m well-educated. I went to a good college. Why didn’t I know about these things?” The same reason I didn’t. There was a lot we weren’t taught.

GG: Journalists talk to people great and small, and we meet an amazing variety of folks in your pages: George Wallace, Daddy King, John Lewis. From your perspective as journalist and commentator, could you please tell us who you found most interesting? Do any of them need to be reexamined in the second draft of history?

FA: I never cottoned to Jimmy Carter. I met him when he was governor of Georgia and found him sanctimonious. We battled quite a bit when he was president and I was the political columnist for the Constitution, and later I helped lead a crusade against the road he wanted to build to the Carter Center. But as I reflect now, he was a truly remarkable figure. It is a cliché to say his ex-presidency was more consequential than his presidency — and it was — but I wish I had been more open-minded and had gotten to know him better.

GG: Late in life, James Baldwin said the sum total of his wisdom was that we could do better. Knowing the figures you’ve encountered, how you’ve covered great historical events, and that you see the book as an attempt to understand the forces that promote or prevent equality, how do you think Americans and America could do better?

FA: I had a friend, a humorist, who used to say, “Before you criticize a man, walk a mile in his shoes. That way, when he gets ticked off, you’ll be a mile away and he won’t have any shoes.” That’s a very funny definition of empathy — but if I have a pitch to make, it’s that white people must work harder to empathize with Black folks.

We never can know what it is like to experience racism, but we certainly can think longer and harder about it, and then try to do things to help. I swore I would not write a textbook advocating a platform of legislation and other tools for use in improving race relations, but we can do our homework, find things we support and get behind them.

Greg Garrett

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Broken covenant: An interview with Vann Newkirk II about ‘Holy Week,’ MLK and white supremacy

‘In a pluralistic democracy’: An interview with Jennifer Rubin

‘What can we forgive?’: An interview with Matthew Ichihashi Potts on Forgiveness