Why did Paige Patterson write a book about biblical counseling? Without rehashing events already thoroughly chronicled by the media and covered extensively in Baptist News Global, we are talking about the former president of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, who counseled women to stay married to abusive husbands and discredited the claims of the sexually abused.

Patterson once was asked what he counseled wives to do when they were abused by their husbands. He responded, “It depends on the level of abuse, to some degree. I have never in my ministry counseled anyone to seek a divorce, and that’s always wrong counsel.

“There have been, however, an occasion or two when the level of the abuse was serious enough, dangerous enough, immoral enough that I have counseled temporary separation and the seeking of help,” Patterson said.

Patterson writing about counseling seems more like David Barton writing about American history or Ken Ham writing scientific papers about creation. There’s a note of inauthenticity.

I thought I would never finish this book. Not because it was difficult or long, but because like taking a cough medicine in 1958, the bitter taste can only be tolerated in small dosages and then taken only every four hours. When I finished the final page, I felt like someone had held a gun to my head and forced me to eat a basket of persimmons.

“When I finished the final page, I felt like someone had held a gun to my head and forced me to eat a basket of persimmons.”

Patterson has written somewhat haphazardly and at little depth, another in the long line of evangelical anti-science screeds.

He makes an incredulous statement when he insists “soft sciences” like psychology must produce the same evidence for verifying their claims and practices as sciences like biology. Surprisingly, Patterson suggests psychiatry exists on a lower level of the science platform than biology.

For a fervent evolution-despiser like Patterson to infer that biology has verified its claims and practices with hard evidence is indeed strange.

Of course, this ignores the fact that advances in the study of the mind, the emotions and the mental disease of humans never have been on stronger scientific ground. Psychiatrists, after all, are trained first as scientists, as medical doctors.

Of course, this ignores the fact that advances in the study of the mind, the emotions and the mental disease of humans never have been on stronger scientific ground. Psychiatrists, after all, are trained first as scientists, as medical doctors.

My overall impressions from reading The Sufficiency of the Bible in Counseling: Like any garden variety fundamentalist, Patterson assumes the throne of Zeus and hurls thunderbolts at unbelievers. He makes assertions but provides no evidence. While he attempts to hide his vicious attack on science in a language of deferment, he comes across more as the “serpent in the garden” than a gentle critic.

My second impression is that when a fundamentalist faces questions about his arguments, he always retreats to the last line of defeat: The Bible. There’s an assumption that waving the Bible around one’s head will magically provide protection from all intellectual attacks.

Patterson swears he has nothing against psychiatry. Then why do we feel like the man on the Road to Jericho when the thieves tell him they don’t mean him any harm? Never trust a Southern Baptist who says he has nothing against any of the sciences.

In the preface, Patterson promises he is not mounting an “assault on the psychiatric industry propped up by big pharma.” He refers, then he attacks. He refers to it as a “bowl of red psychotherapeutic pottage.” He also says one can read the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders with the same profit obtained from a reading of Bulfinch’s Mythology.

Any person with an interest in exploring the weaknesses in psychotherapy would find a much more delightful and stimulating read from We’ve Had One Hundred Years of Psychotherapy and the World Is Getting Worse, a 1995 work by James Hillman and Michael Ventura. This audacious series of interrelated dialogues and letters deconstructs the legacy of psychotherapy but also practically every aspect of contemporary living — from sexuality to politics, media, the environment and life in the city.

“The Sufficiency of the Bible in Counseling offers no new insights.”

The Sufficiency of the Bible in Counseling offers no new insights. The boring attack on science has been more robust from other anti-science proponents in the young earth creationist field. For instance, many evangelical-to-fundamentalist theologians are convinced their worldview is the final truth about reality, that science is false and the conflict between science and religion can’t be resolved unless the scientific community returns to a pre-scientific framework. This is Patterson’s stance, but more sophisticated thinkers like attorney Philip Johnson and Reformed philosopher of religion Alvin Plantinga make Patterson more of a “hewer of wood and a carrier of water” — a Gibeonite among the people of God.

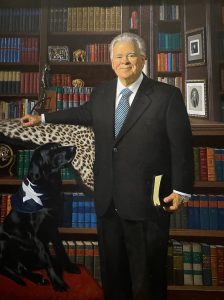

This portrait of Paige Patterson hangs in the Rotunda at Southwestern Seminary. It was under Patterson’s leadership that enrollment began a steep decline while spending went up.

Patterson seems to believe counseling according to Scripture means knowing how God sees a matter (no small feat), finding the steps to implement God’s perspective and seeing the results in your own life. Patterson emphatically adds, “The deeply committed, thoroughly biblically literate believer can do this one assignment of presenting God’s truth with greater alacrity than even the most educated professional.”

As a master of divinity graduate of a Southern Baptist seminary, I went forth to my first church after graduation armed with nothing but a Bible and two classes in Christian counseling. This did not prepare me for the clinical depression, mental disorders and emotional upheaval hiding behind the sober, serious, sincere fundamentalism in the minds and hearts of my congregation.

I would have found Patterson unhelpful and profoundly disturbing if I had used his approach in attempting to help a church member who had a habit of calling the parsonage on a Saturday night and “cussing me out.” On Sunday morning, he would appear, once again sober, greet me as “Brother in Christ” and teach his adult Sunday school class.

Nor did I know what to say to a woman who called every Sunday morning after worship to tell me she had listened to the sermon on the radio. She suffered from a fear of leaving the house. In her conversations with me, she confessed all she really wanted to do was “have sex with the Holy Spirit.”

Patterson asserts, “Biblical counselors know more about this ministry than a wandering theologian.” What in the world is a wandering theologian? And why does Patterson think there would be something wrong with being a wandering theologian? Did not Abram go forth not knowing where he was going? Did not Israel wander in the wilderness for 40 years? And what of Elijah hiding in a cave? Or John the Baptist, the wilderness prophet who came preaching, “Repent?”

“Patterson argues the biblical counselor must choose between Freud, Skinner and the ‘soft science’ of psychology or God’s word.”

Stuck in the usual dualism of fundamentalism, Patterson argues the biblical counselor must choose between Freud, Skinner and the “soft science” of psychology or God’s word. He never considers how the trained pastoral counselor may be better equipped by training in psychology and the Bible. He seems locked into the assumption that psychiatrists are a bunch of atheists. This means his fundamentalist mindset hasn’t changed from the 19th century’s original fundamentalists who thought biblical critics had to be under the influence of mind-altering drugs.

Patterson shows his cards in his Prelude: “Our province is …. to point out from Scripture what is revealed about the mind of God. What has God revealed to us about gender, sexual acts, sobriety, anger, race, justice.” He waits until chapter seven to play his hand: “The Hallowed Explosive: Sexuality.”

I can’t decide if Patterson is being playful with the word “explosive” in reference to sex or if, more likely, he is expressing his outrage over human sexuality in our culture. I would have thought it more interesting if Patterson had explicated the sexuality of the Song of Solomon instead of the dreadful notions of fundamentalism about sex.

Patterson comes up far short of Carlyle Marney’s counseling ministry at Interpreter’s House. Marney offered ministers far better advice than Patterson: “Christianly, we have more to say to, for, with, on account of, and in behalf of man than from any other stance we could take: If we have done our homework. … By homework I mean that decades-long process of inquiry, hat in hand … addressed to competent psychology, psychiatry, sociology, history, drama, art, daily affairs, interpreted by a growing biblical memory, contemporary experience, theological acumen, into some kind of understanding of our Christian advantage.”

Thank God for Marney and thousands of faithful clergy everywhere who see a “big house” with rooms for psychology, theology, sociology, science, religion, history and all the disciplines struggling to knock, seek and ask in search of the truth. Against the profoundness of Marney, Patterson is a Naaman outraged that the preacher has not come out to meet him, do a little dance, and some magic and cure all the mental and emotional diseases of the human mind.

As much as Patterson believes in the awfulness of sin, he seems ill-equipped to deal with a society filled with people whose name is “Legion” — who no longer dwell in graveyards but now haunt schools, neighborhoods and malls with a deep mental dis-ease.

Patterson’s plodding review of dissident psychologists, his piling up of “scary” testimonials against psychotherapy and his pronouncements of the all-sufficient power of the Bible read more like a revival sermon than a scholarly critique of psychology.

Rodney Kennedy

Rodney W. Kennedy is a pastor and writer in New York state. He is the author of 10 books, including his latest, Good and Evil in the Garden of Democracy.