Three years ago, when I first started to write Hope in Disarray, the world was a very different place. It seems that the world back then was churning through time at rapid speed, unaware and untroubled by the destined forces that would pummel through the planet, humanity and all of creation.

Before, it was almost every week that I was rushing to get on another plane, setting off to a new city or country without so much time as to blink. I was writing a book on hope, reacting to and understanding the world through a specifically global, privileged tinge.

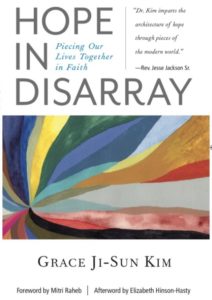

Grace Ji-Sun Kim

Like many others, I thought this was what it meant to live; to continue to live in the world freely, without the thought of my immediate impact, without acknowledgement of the future I was shaping that would come after me. I was not alone in such a sentiment; the world reflected these ignorances.

We continued to work overtime. We continued to rush from work to home. We continued to worsen climate change. We continued to rage on in unending wars. We continued to concede to racism. We continued to turn the other cheek and move ahead. Life was running on autopilot, perpetually moving forward without any end in sight.

Today as I write this, I have finished the book in a much different time. Once lodged into the obscure distance, it seems it has finally started to emerge — an end in sight. It has come more than a year after the first eve of the pandemic, where the countless fire-rounds of horrifying death rates, political conflicts, racial reckonings, climate disasters and economic collapses have come to an eventual lull, and where we are left with nowhere to be and nowhere to turn other than at ourselves.

In this sense, the pandemic has been the great equalizer fated to befall us for centuries. In other ways it has not, devastating underprivileged countries and communities with senseless loss and torment. Regardless, none of us are immune to its wide-ranging effects, which can be felt universally through our collective isolation.

This past fall, I became suddenly ill and was hospitalized. For months, I suffered from intense vertigo, blurred vision, difficulty breathing and debilitating migraines that rendered me bedridden, isolated, immobile and too weak to speak. It was a period when I spent the majority of time sleeping, dreamlessly intoxicated by the comatose of the illness.

“There were moments in the night when I was abruptly jolted awake, suddenly aware of everything.”

But there were moments in the night when I was abruptly jolted awake, suddenly aware of everything. In those moments, I found myself in a strange, liminal space of reflection; neither happy nor sad, but simply resting. In those moments, I prayed. I heard the prayers of my late mother, heard the prayers of my children from the future. I prayed, and hope quietly bloomed.

As we go through undesirable difficulties, we are called to leave the comfort of our darkness and despair and instead cry out to God. Hope is central to the faith journey. It is the bedrock of Christian life. It is how we all, in some way or another, discover God. It is how we all, in some way or another, continue to move forward in time when we feel we simply cannot.

In the midst of a world pandemic where death surfaces all around us, we can only do the dignified thing, the courageous thing: Hope.

Hope is not blind optimism. Hope is not pleading for your desires. Hope is not asking for change. Hope is inciting action. Hope is what leads revolution. Hope is what defeats injustice and apathy. Hope is the force that requires us to cling onto God and act.

“Hope is inciting action. Hope is what leads revolution.”

In the foreword of my book, Mitri Raheb offers words of wisdom on how to understand hope: “We realized that our struggle is not a sprint, but rather a long marathon. In a marathon, hope is the art to breath. It is the art to keep one resilient so as not to lose heart or sight of the goal. Hope is the power to keep focusing on the goal while taking small steps toward that future. Hope doesn’t wait for change to come. Hope is vision in action today. Hope is living the reality and yet investing in a different one.”

In her afterword, Elizabeth Hinson-Hasty writes, “Our Christian hope emerges from the awareness of our deep connection to God, others and the planet upon which we depend for sustenance.”

More than ever, we need hope to fuel us forward. Writing Hope in Disarray was my way of addressing the ways in which our connection to God can be enriched during times of great suffering and hopelessness. I cover issues such as climate change, racism, sexism, gun violence, sexual abuse and family dynamics — which can take us down a path of anguish, with a re-defined sense of hope.

Hope provides joy as promised in Scripture (Romans 15:13). Therefore, we cling to hope in a world of disarray and chaos. My wish for the book is to inspire people of faith, spiritual groups and the church to live a life of empathy and social action. This is what God requires of us: “To do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8).

In my final thoughts of the book, I share this: “In this parting, after you turn the page, close the book, return to life, shut your lids for a night’s rest, and feel darkness swathe all around, call out for something. Call out for love; call out for peace; call out for light; call out for mercy; call out for God. Reach out, not for the purpose of gaining something in return, but because the call itself is the gift.”

Call to God. Cling to hope. Work for justice.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 20 books.

Grace Ji-Sun Kim is professor of theology at Earlham School of Religion in Richmond, Ind., and earned a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto. She is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author or editor of 20 books.