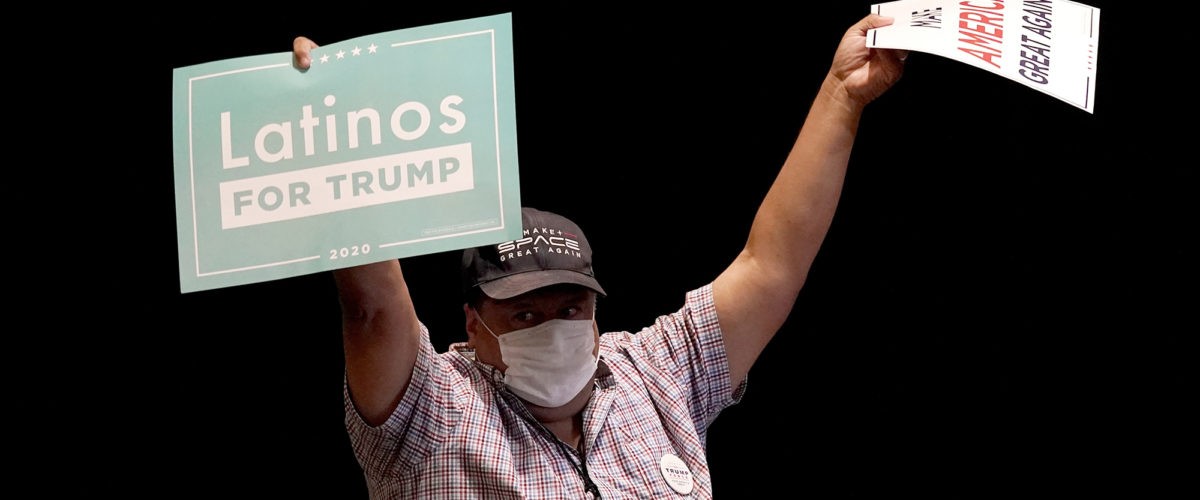

Why would Hispanic voters embrace a president who has been called the most racist and anti-immigrant in modern history? The most likely answer: religion. But even that isn’t a complete answer.

“There are not significant gender or age divides among Hispanic Americans when it comes to support for (Donald) Trump. There are, however, distinctions by religious affiliation,” according to Natalie Jackson, director of research for Public Religion Research Institute.

In a post-election analysis published on PRRI’s website, Jackson addressed the question that has perplexed political observers both in 2016 and 2020: Why is there Hispanic support for this president, and why has it increased in some places?

Exit polling indicates that around one-third of Hispanic voters this year favored Trump over Joe Biden.

Exit polling indicates that around one-third of Hispanic voters this year favored Trump over Joe Biden, and more than four in 10 voted for Trump in the swing state of Florida.

Both these numbers appear to have grown from 2016 to 2020. Exit polls in 2016 showed 28% of Hispanic voters nationwide favored Trump, as did 35% of Hispanic voters in Florida.

“These initial estimates might seem surprising to some, given many of Trump’s anti-immigrant stances and refusals to condemn white supremacy,” Jackson noted. “However, a closer look at data from PRRI’s 2020 American Values Survey reveals that a sizable minority of Hispanic Americans concur with Trump’s views.”

What other data explain

Among the data she cited to make her case: “A majority of Hispanic Protestants approve of Trump’s job in office (57%) and his performance with the economy (58%). Hispanic Catholics and those who are religiously unaffiliated are considerably less likely to approve of the president’s job in office (27% and 16%, respectively) or his performance with the economy (42% and 28%, respectively).”

All of which goes to a point being made in various media outlets by other observers and interpreters of Hispanic culture: There is no “Hispanic vote.” Even the term “Hispanic” is part of the problem in understanding this.

The 2020 election results “confirmed what I’ve been saying for about three or four election cycles: that Latinos are not a monolith writ large, and that Hispanic evangelicals are quintessential swing voters,” Gabriel Salguero told Religion News Service. Salguero is founder of the National Latino Evangelical Coalition and Florida resident.

Just as Hispanics overall are not a monolithic group, neither are Hispanic voters, Olma Echeverri, a former member of the Democratic National Committee, told the Charlotte Observer.

“There is no Latino voting bloc. There’s no such thing as the Latino vote.”

And writing for Marie Claire, Luisa Marcela Ossa, associate professor of Spanish at La Salle University, insisted too that there is no coherent Hispanic vote: “It isn’t a voting bloc. I repeat: There is no Latino voting bloc. There’s no such thing as the Latino vote.”

What’s in a name?

Even the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” add to the confusion, she said.

“’Hispanic’ was adopted in the 1970s by the U.S. Census Bureau as an attempt to track people directly from, or descended from, Spanish-speaking countries, including 20 nations from Latin America and Spain itself, but not Portugal or Portuguese-speaking Brazil.”

On Feb. 19, 2020, Joe Biden walks on a picket line with members of the Culinary Workers Union Local 226 outside the Palms Casino in Las Vegas. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

Then by 2000, “Hispanic” and “Latino” began to be used interchangeably, now followed by newer words such as “Latinx” and “Latine.”

“But regardless of one’s preferred term, it’s an artificial category that lumps together people of all kinds of racial backgrounds and diverse national origins, ones with distinct cultural norms and political histories,” Ossa said.

This is particularly true in Florida, Salguero told RNS.

He identified two separate and key Hispanic voting blocs in Florida — ones with ties to Cuba, which Trump carried with 55% of the vote, and another with ties to Puerto Rico, among whom only 30% supported Trump.

Each of these voting blocs — Cubans (29%) and Puerto Ricans (27%) — represent about the same percentage of the Florida electorate. Evangelical Christians overlap with both groups.

Religion a key determinant

And it is that faith identification, according to PRRI’s Jackson, that is most determinative.

“Religion is the largest demographic divider among Hispanic Americans.”

“The differences between Hispanic Protestants, Catholics, and those who are religiously unaffiliated persist through many questions in the survey, with Hispanic Protestants notably more pro-Trump, conservative and Republican than Catholics or those who are religiously unaffiliated,” she wrote. “Religion is the largest demographic divider among Hispanic Americans, excepting only partisanship, and the data show clearly that many have views that align with Trump and the Republican Party. It should come as no surprise, then, that many voted in that direction.”

Among all Hispanic Americans, 37% identify as Democrats, 25% as independents and 21% as Republicans, according to PRRI. However, Hispanic Protestants are more likely to identify as Republicans (32%) and to consider themselves ideologically conservative (39%).

These differences show up in specific issues that, to those outside the Hispanic culture, might be surprising.

For example, PRRI reports that 35% of Hispanic Americans support building a wall at the southern border with Mexico to keep immigrants out, and that support rises to 48% among Hispanic Protestants. Also, 45% of Hispanic Protestants support a law preventing refugees from entering the country.

These differences start to break down on a few more specific issues, PRRI reports, such as the Trump administration’s family separation policy and policies that allow children who were brought into the country illegally to gain legal status. Those are less likely to be affirmed even by Hispanic Protestants.

While six in 10 Hispanics nationwide believe Trump has encouraged white supremacist groups, Hispanic Protestants are less likely to believe that, at only 44%. Hispanic Protestants are also twice as likely as religiously unaffiliated Hispanics to say that police killings of Black Americans are isolated incidents (50% versus 22%).

North Carolina

In North Carolina, Hispanic voters were projected to account for between 5% and 6% of the total electorate this year, not nearly the influence in other Republican-leaning states like Florida and Texas.

But unlike in the national exit poll data, North Carolina Hispanics appear to have been divided by gender. The Charlotte Observer reported that Trump was the winner among Latino men, but “lost in a landslide” to Biden among Latino women.

Even so, country of origin also played a role in North Carolina.

Mecklenburg County, which includes the city of Charlotte, counts about 137,000 Hispanic residents or 13% of the county’s population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That includes residents who have come from Mexico primarily, but also from Honduras, El Salvador, Puerto Rico and elsewhere.

The Observer explained: “What does that mean politically? For starters, Cubans tend to vote Republican; Mexicans and Puerto Ricans usually support Democrats.”

And what of Black Latinos?

To add yet another layer to the story, generalized focus on the “Latino” vote ignores the reality of Black Latinos.

The Census Bureau reports that New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Connecticut have the highest percentages of Hispanics identifying as Black, partly because of large Puerto Rican and Dominican populations.

That makes looking to Florida for an understanding of the Latino vote misleading.

“90% of Latinos in the Miami-Dade area identify as white.”

Writing in Marie Claire, Professor Ossa explained: “Miami-based journalist Lizette Alvarez notes that 90% of Latinos in the Miami-Dade area identify as white. She adds that over the summer when there were Black Lives Matter protests, Miami was one of the few places ‘Cubans for Trump’ counterprotests were regularly held.

“In Texas, the largest groups are Mexican and Central Americans. A recent article in The Dallas Morning News describes the lack of unity among Latinos along the border regarding immigration and other issues. In fact, the article points out that many Latinos on the border work for the federal sector, including as agents for ICE. In Philadelphia, the largest groups are Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, and national polls have shown that Puerto Ricans and Dominicans strongly favored Biden.”

Joining the chorus of other writers from Latin America, Ossa concluded: “It’s time the media stops reducing Latinos to clever soundbites at election time. There’s a world of scholars, activists and community members waiting to be heard. Let’s hope our recent election is the much-needed wake-up call that begins a change.”