After moving from Seattle to Dallas in 2015 to teach at Southern Methodist University, I decided to do something, well, important with some leftover funds. With a history of searing headaches, I wanted to introduce ancient authors who wrote in unvarnished ways about pain to modern medical practitioners who labor to palliate pain.

People told me, “You’ve got to meet Bob Fine!” He’s an internist who now serves as director of the Office of Clinical Ethics and Palliative Care at Baylor Scott and White Health.

Jack Levison

Robert Fine

So I did. Over hours of exhilarating front-porch conversations, it became obvious that a biblical antiquities professor and a palliativist and ethicist had lots to learn from each other.

Encouraged by my friendship with Bob, I gathered an improbable cluster, by any measure, of physicians and scholars who met to wrest insight for palliative care from ancient texts about pain. We met informally twice in New York City, thanks to Brooke Holmes, Goheen Professor of Classics at Princeton University.

About the same time, Mauro Ferrari, CEO of the Houston Methodist Research Institute, invited me to a conference hosted by the Roman Catholic Church’s Pontifical Academy for Life, along with Houston Methodist Research Institute and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. I introduced Mauro to Bob Fine. Bob and I couldn’t help but notice the speakers at this symposium were an array of luminaries in the field, so we met immediately with Mauro to discuss the prospect of a book. We landed on a publisher, and off we went.

Bringing the book together wasn’t easy. COVID blindsided us, of course, and our authors dove headlong into an unrelenting and unwelcome reality. Bob, too, was exhausted, dealing with the barely living and the dying — and the ethical matters COVID raised. For my part, I tussled with the more manageable matter of hastily patched-together online teaching.

The book was hard to pull together, too, because doctors — and lots of the essayists are doctors — are proficient at writing scripts and technical scientific studies, but essays are another beast altogether. Time and again, Bob and I pressed for stories. “Open with a story!” I’d bark my edits. “Opaque. Insert a story!” we’d advise. “Too technical. Tell a story!” Bob nudged.

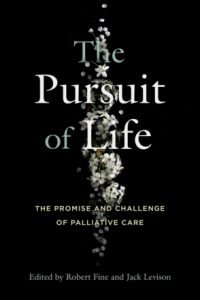

And so this book, written by a slew of luminaries in the fields of palliative care, ethics and chaplaincy, is really a storybook. Not, of course, a charmed or charming book of storybook endings. But a book full of significant and substantial stories.

Siddhartha Mukherjee, in The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, tells us that “medicine … begins with storytelling. … Patients tell stories to describe illness; doctors tell stories to understand it. Science tells its own story to explain diseases.”

The Pursuit of Life is replete not with textbook definitions or professional society manifestos, but with the power of stories.

The Pursuit of Life is replete not with textbook definitions or professional society manifestos, but with the power of stories.

A pioneer in palliative care nursing, Connie Dahlin, begins the book “in the corner of a living room,” where “Kate, a woman in her thirties, lies dying of breast cancer.” Similar stories dot the essays by pioneers Declan Walsh, Neil MacDonald and Eduardo Bruera, whose memoirs — and unvarnished memories — appear only in The Pursuit of Life.

Daniel Sulmasy, ethicist, internist, Georgetown University philosopher and one-time Franciscan friar, tells the story of a “fiercely independent” monk, “a heavy smoker and hard drinker,” who refused all help, so as not to burden his community. Sulmasy opened the door, only “to find him lying in bed, emaciated, naked, delirious and covered in his own feces.”

Andy Achenbaum, once a deputy director of the Institute of Gerontology at the University of Michigan and recipient of the Geronotological Society of America’s Kent Award, tells his own story. “Like most laypersons thrust into the role of caregiving, I turned to the internet,” he confides, when his wife “spent more than 10 weeks hospitalized with near constant pain” with insufferable cancer.

Joe Calandrino, who worked for decades in a VA hospital on Long Island, tells us how “suffering and dying bodies speak” through people like Crystal, who died of AIDS, Maurice, with his body “splayed, displayed and vulnerable,” and Vincent, with “a wound deeper than skin and bone.”

Jim Cleary, of Indiana University, tells us about Artur, a former KGB colonel, whose “pain was often so intense he could not move.” In the absence of opioids, pain relief came first in a bottle of brandy, and then, Cleary learned, in “the service revolver that he kept loaded ‘for when the pain gets too bad.’”

“We all have stories, and most of us wish our doctors would listen to them.”

Joe Fins, one of America’s leading bioethicists, traces the meaning of “time to death” through the stories of Tom, in Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie, and Mr. Charles, “a grizzled old shoe salesman” in “a hotel room in the sweltering Mississippi Delta” in Williams’ Gold Watches.

Kathy Kirkland tells stories about using stories — yes, you read that right — in medical school to compel budding doctors to live in the tensions of life and death.

We all have stories, and most of us wish our doctors would listen to them. And when we fall ill, we wish our friends wouldn’t turn away in embarrassment, shamed by a lack of words — because we just need them to listen. In this book, Bob and I gather profound stories told by some of the world’s brightest minds in medicine, ethics and chaplaincy.

There are many more stories in this book. And the last of them? Our Italian friends tell us about Lucia, “a 17-year-old patient with metastatic refractory soft-tissue sarcoma in terminal phase,” whose dream is the final story in The Pursuit of Life. Her story — like other stories in this book — tells us patients are more than their disease: “We learn about life, about death, and about the inevitability of being suspended between them.”

In Lucia’s story and so many others in this book there is hope, confidence and the courage to dream, which, in the end, is why this book is titled not The Destiny of Death, but The Pursuit of Life.

This article originally appeared at BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care and is republished here with permission.

Jack Levison holds the W.J.A. Power Chair of Old Testament Interpretation and Biblical Hebrew at Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University.