Gazing around the auditorium, I knew I was out of place. A lot of indicators pointed to this fact, but none more so than the observation I was several inches taller than those who filled the seats around me.

This is an unusual position for me. Scholarship offers from powerhouse college basketball programs such as North Carolina, Kansas and Indiana never found their way to my mailbox during my adolescent years. Average height doesn’t often warrant such coaxing from “blue blood” schools. I basked briefly in the knowledge I would most likely dominate those around me in a pickup game of “HORSE.” Maybe.

Justin Cox

Besides slightly towering over them, my presence raised the median age by a few years. While I don’t feel that long in the tooth, my fellow sojourners surrounding me were likely still losing baby teeth. My elder statesman status for this outing placed me in the category of an adult chaperone. It is a rank I willfully accepted so that I might be in attendance to hear the guest speaker.

Rep. John Lewis was visiting communities to discuss his graphic novel, March, a work schools throughout the state had included in their reading program. The students and I gathered to hear Lewis share about his time as a civil rights leader and how it compelled him to serve in Congress.

Near the end of his talk, Lewis charged the young crowd with what many consider his mantra, one becoming his epitaph: “Get in good, necessary trouble.” Afterward, he greeted those who wished to grab a picture or ask a quick question. I made my way down front, trying to keep an eye on the group I came with.

By chance, Lewis appeared right in front of me. Our brief encounter included an old-fashioned handshake and an exchange of pleasantries. “I really enjoyed March, and I was glad to see Will Campbell in there,” I shouted over the noise. Giving a quick smile, Lewis paused before delivering back to me: “Oh, Will! Yes, Will Campbell was a friend of mine.” We nodded and departed one another, him ushered away and me with a story I still treasure.

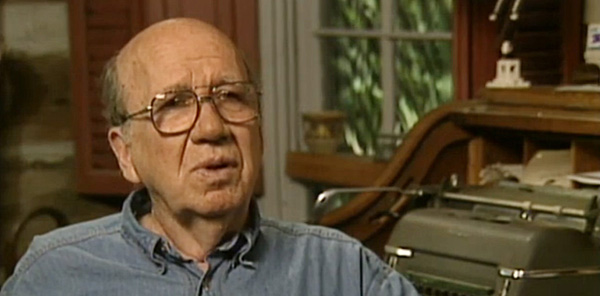

Recently, I thought about that moment with Lewis and our shared appreciation for Ol’ Brother Will. Campbell would have celebrated his 98th birthday last week; he passed in 2013. His absence this past decade has left many a renegade Baptist without a reluctant iconoclast icon.

While I did not know the man personally, my mourning for his absence rests with what he embodied. He showed me and many others what was possible.

A figure who became something of a folk hero, Campbell openly rejected the accolades extended to him. He deflected his significance in the civil rights movement, the rubbing of elbows with country music stars and his elevation as a modern-day prophet of the South. Dodging labels created and thrown at him from both the right and the left, he adopted a persona of one unwilling to be the head of anything or any cause.

This was his life. After serving one small church in Louisiana, he left traditional ministry for good. Instead, he wandered as a minister of disruption, a role that pushed him into the public square. On several occasions, someone asked Campbell to describe his “ministry.” In those moments, he let the questioner know he did not have a ministry but a life, and this is what he felt called to do with it.

Campbell’s life and work comprised an experiment in agitation. Underneath the wrappings of flesh and bone dwelt a constantly churning spirit of confrontation. A spirit willing to put those he loved — and Campbell believed “if you’re gonna love one, you’ve got to love ’em all” — in uncomfortable positions.

Besides his wide-brim Amish hat and gnarled cane, Campbell’s wardrobe included restless shoes and vex-inducing eyewear. Whether calling out the sanctimonious attachment to opulent sanctuaries or informing a would-be acolyte to do work where they were instead of coming to sit at his feet, he was a man my maternal grandfather would call a “shit stirrer.”

Holy agitators. Ministers of disruption. Divine dissenters.

As I thumb through Campbell’s work and re-read articles about him, I realize I miss a man I never knew but only read and heard about from others. Maybe Campbell thought something similar when he recalled Roger Williams, Isaac Backus, John Leland and those Anabaptists he understood to be his contrarian forbears. A cloud of shit-stirring witnesses whose very presence pressed others to see faith and a world differently.

While I did not know the man personally, my mourning for his absence rests with what he embodied. He showed me and many others what was possible. We didn’t need to feel pressured to wear robes or sit under steeples in our calls, and we sure as hell shouldn’t consider ourselves less than others for choosing not to.

In fact, Campbell charged us to challenge such things and suggested maybe, just maybe, to have a little fun while doing it. To go in and pull the rug out from under empty religion where status quo is preferred over the radical teachings of a lowly Galilean.

He helped me see and name a nonconforming covenant I’ve been called to. One of taking the holy vow to be concerned with inflicting good and necessary trouble when and where I can. So, like Lewis, I say, “Oh, Will! Yes, Will Campbell was a friend of mine.”

Keep making us uncomfortable, Will. Keep us squirming in our pews.

Justin Cox serves as senior pastor of the United Church of Lincoln, Vt. He received his theological education from Campbell University and Wake Forest University School of Divinity. He enjoys reading, amateur gardening and helping his spouse, Lauren, chase their daughter, Violet, all over the village of Lincoln. He is an ordained minister affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and is currently enrolled in the doctor of ministry program at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.

Related articles:

‘Bootleg preacher’ Will Campbell dies

Remembering Will Campbell: does anyone here NOT know Amazing Grace?