In what appears to be a regularly repeating phenomenon, many Christians seem to have become convinced that Christ, despite his omnipotence and omnipresence, has gone missing from our schools.

They urge the simple fix for this divine absence is for each and every school to prominently post a copy of the Ten Commandments, offering a timely reminder to our elementary school students not to covet their neighbor’s ox and to keep the Sabbath holy.

Personally, in the wake of a general election in which the vast majority of white American evangelicals voted for a profane, vindictive, racist, xenophobe like Donald Trump, I’m much more interested in making sure Jesus Christ doesn’t somehow disappear from our churches.

As such, I’m willing to take a pass on plastering carboard cut-outs of Moses’ stone tablets in school lunchrooms, but I would love to see Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail become mandatory reading for all white American Christians.

August 1963

It is August 1963 and, as King looks out from his jail cell in the midst of the Civil Rights struggle, he takes up pen and paper to call out a great sin. He isn’t moved to do so by the hateful bigots spitting on Black children for daring to attend the same school as white children, or by the equally hate-filled police officers who were brutally clubbing unarmed, nonresisting, freedom marchers to death, or close to it, in the name of “law and order.”

No. What has motivated King to write his epistle is a collection of white Southern pastors who had labeled him an “extremist” and who had used their pulpits to call for an end to the acts of nonviolent civil disobedience courageous Black men and women were then undertaking in opposition to Jim Crow laws across the South.

King’s letter should be read in its entirety to do it full justice. I hope, though, that even my paraphrase of his majestic prose might resonate with white American Christians who seem equally lost today.

“I’m much more interested in making sure Jesus Christ doesn’t somehow disappear from our churches.”

King rightly took issue with the pastors who had accused him of creating a tension that disturbed the unity and peace of society. In so doing, he explained he was “not afraid of the word ‘tension’” even though he had “earnestly worked and preached against violent tension.”

Rather, “there is a type of constructive nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth,” he said The polarized world in which he found himself had no need for more men and women who would stand mute in service of a false unity grounded in prejudice and bigotry but was in desperate need of “nonviolent gadflies” whose very presence could “create the type of tension in society that will help men to rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood.”

As King explained, the need for such gadflies is particularly acute whenever, as a society, lawfulness has been cut free from its roots in justice, forcing Christians to realize saying “yes” to Christ may necessitate saying “no” to an unjust law.

Everything Hitler did was legal in Germany

In explaining the crucial difference between just and unjust laws, King called his fellow Christians to remember that while “everything Hitler did in Germany was ‘legal,’” “it was ‘illegal’ to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany.”

That realization was fundamental to King’s view of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience, as he was certain that “if (he) had lived in Germany during that time, (he) would have aided and comforted (his) Jewish brothers even though it was illegal.”

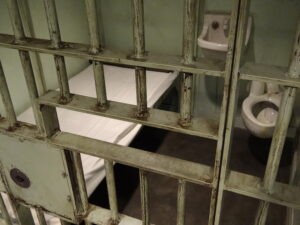

A recreation of Martin Luther King’s Birmingham jail cell, at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis.

Yet, when he looked to the white Southern churches of his day, he saw Christians proving to be “more cautious than courageous,” “remain(ing) silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained-glass windows” rather than loving their Black brothers and sisters as themselves.

He confessed he had “almost reached the conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councilor or Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

For King, a silent, unquestioning obedience to a status quo marked by pervasive and often violent racism was, itself, sinful. Therefore, Christians must come to realize that “the question is not whether we will be extremist, but what kind of extremists we will be.”

For the vast majority of white Southern Christians who purported to share King’s faith but not his skin color, the election to stand silent was its own form of extremism — an extremism of support for a culture that could not stomach the idea of Black people daring to demand that they be treated like human beings.

For King, this state of affairs did not simply pose a hurdle to the Civil Rights Movement. It threatened the vitality of the church, itself.

He called on white Southern Christians to recall “there was a time when the church was very powerful,” a time when “early Christians rejoiced when they were deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed.” Because of such sacrificial faithfulness to the kingdom of God and its values, the church was “not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion.”

Instead, it became “the thermostat that transformed the mores of society,” he wrote.

In stark contrast, the contemporary church of King’s day more often was “a weak ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound.” The world at large suffered from the willingness of white Southern Christians to abandon a radical faithfulness and commitment to the teachings of Christ in favor of a role as “the arch supporter of the status quo” as, “far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s often vocal sanction of things as they are.”

‘Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability’

At its heart, the Letter from Birmingham Jail was a heartfelt plea for white Southern Christians to view their moral and theological convictions as something more than a basis for private, passive goodwill and to instead hear the words of Christ as a clarion call to public, positive action.

Martin Luther King delivers a sermon on May 13, 1956, in Montgomery, Ala. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

In King’s own powerful words: “We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words and actions of the bad people. We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of men willing to be coworkers with God.”

My prayer is that King’s truly prophetic Letter from Birmingham Jail will speak to white American Christians today at the dawn of another Trump administration.

Will our churches settle for the “negative peace” of a lack of tension by simply refusing to address important issues that might be branded by some as “political”? Or will enough pastors and laypeople take on the holy calling of being the gadflies needed to foster a “positive peace” — a peace grounded in justice — by calling out greed, misogyny, racism, xenophobia and homophobia for the sins that they are? Will white American Christians lovingly and courageously open our churches and homes as sanctuaries for our migrant neighbors threatened with deportation, showing that, like King, we would have chosen the justice of caring for our Jewish neighbors over a slavish devotion to the unjust and murderous “lawfulness” of the Nazis?

Will we be salt and light for a world in need of both, or will we just add to the shadows?

Ultimately, the question is not whether white American Christians in the coming year will prove to be extremists or not. The question is whether we will choose to be extremists for Christ or extremists for Trump, and the answer to that question will have massive repercussions, both for our neighbors and for our churches.

Chris Conley is an attorney and graduate of the University of Georgia and of the Emory University School of Law. He and his wife, Mary, live in Athens, Ga., where both are members and deacons at First Baptist Church. They have one son, Aaron, who also is an attorney, and a miniature schnauzer, Oso, whose career path remains uncertain.

Related articles:

The anger and disappointment I feel for my fellow Americans | Opinion by Chris Conley

What will it take for you to care about transgender people? | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Civil rights advocates already planning to challenge mass deportations