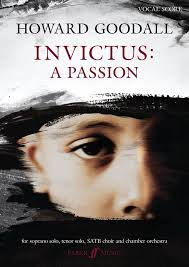

When Howard Goodall set out to write a fresh choral work on the Passion of Christ, he knew full well the giants who had trod this ground before, especially the ever-present Johann Sebastian Bach.

Yet he also knew the overwhelming majority of Christianity’s great choral works spoke from a male perspective — even though women figure most prominently in the Holy Week and Resurrection story.

Thus, he determined that building a great choral work around women’s written voices would provide the kind of fresh perspective he sought.

Howard Goodall

Goodall, who lives in London, is one of Britain’s best-known composers of choral music, stage musicals, TV and film scores. His settings of Psalm 23 and “Love Divine” rank among the most performed of modern sacred music, and his Eternal Light: A Requiem has been performed hundreds of times and received numerous awards. Fans of PBS and the BBC will instantly recognize his setting of Psalm 23 as the theme to the quirky TV series “Vicar of Dibley.”

Three years ago during the Lenten season, his Passion work, titled Invictus, premièred at St Luke’s United Methodist Church in Houston, which had commissioned the piece. It then premiered in London, was released on CD and has been performed in churches and concert venues.

“Whenever I approach the writing of one of the great historical choral forms — forms that have had multiple interpretations from a wide variety of composers and traditions — I start by asking myself, ‘What, if anything, am I adding to the sum total of the existing repertoire?’” he explained in a recent interview. “Am I simply retreading a path well worn by the feet of my predecessors, using the same texts, the same structure or the same performing forces but replacing their musical notes for mine, or am I hoping to be more innovative, perhaps to come up with a formula that is fresh, different, or just of our time rather than theirs?”

J.S. Bach

Particularly when approaching the Passion of Christ, any contemporary composer labors in the shadow of Bach, he noted. Bach’s St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion not only are the best-known of the genre but also among the most beloved.

“We all take Bach’s Leipzig masterpieces as our starting point,” Goodall explained. “We’d be crazy not to. However, not being Bach is as important to me as it is to learn its lessons, so my first point of divergence, I knew from the outset, was going to be a change in the choice of texts, since his versions are imbued with the particular Lutheran telling of those two Gospels, with all the associations and prejudices — yes, I’m afraid the Lutheran take on Christ’s trial and death, one which places blame squarely on the Jews, rather than, for example, the occupying Roman military regime, is uncomfortable for us in the 21st century even if we utterly adore the magnificence of Bach’s settings — that come with the mindset of that time in early 18th century Saxony.”

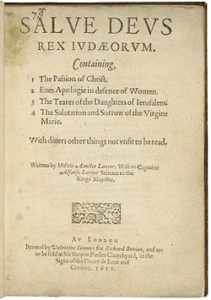

Aemelia Lanyer

Thus, Goodall set out to find texts that would reflect upon the biblical story through the prism of contemporary experience. That’s how he encountered the dramatic poetic version of Aemilia Lanyer (also known by the surnames Lanier or Bassano), cited by the Poetry Foundation as “the first woman writing in English to produce a substantial volume of poetry designed to be printed and to attract patronage.”

Lanyer was a contemporary of Shakespeare, and scholars debate sometimes wild theories about her relation to the Bard, his possible references to her in his work or even speculation that she penned some of the works attributed to him. Goodall said his own research does not support that conclusion, titillating as it may be.

Yet her poetry on the Passion — Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews) published in 1611 — was groundbreaking for its time. Her biography on the Poetry Foundation website cites it as being “the first genuinely feminist publication in England.” Further, “the poem on the Passion specifically argues the virtues of women as opposed to the vices of men, and Lanyer’s own authorial voice is assured and unapologetic.”

Yet her poetry on the Passion — Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews) published in 1611 — was groundbreaking for its time. Her biography on the Poetry Foundation website cites it as being “the first genuinely feminist publication in England.” Further, “the poem on the Passion specifically argues the virtues of women as opposed to the vices of men, and Lanyer’s own authorial voice is assured and unapologetic.”

That was the hook Goodall needed for his work.

“It struck me immediately as rather different in attitude to others, by men, that I’d studied,” he said. “Of course, this wasn’t a 21st century text, far from it … and its text is difficult to read in places, but it is without doubt a female perspective of the story, concentrating on the depth of suffering and injustice of Christ, bringing into the court scene Pilate’s wife, pleading on Jesus’ behalf, and focusing on the deep distress of his mother and his friend Mary Magdalene.”

Christina Rosetti

Armed with this good find, he sought out other women writers — although not exclusively women — to complement her words. This led him to Christina Rossetti’s Mary Magdalene and the Other Mary poem, and to Frances Ellen Harper’s Slave Auction, “both of which are concerned with the impact on women of witnessing the torture and/or death of their child/loved one,” he noted.

Ella Wheeler Willcox

Next came Ella Wheeler Willcox’s Gethsemane, a 20th century examination of the crisis moment of Gethsemane.

Even male authors brought into the Invictus text get a different treatment in light of Goodall’s intent to tell the story from a female perspective. Words from Isaac Watts’ well-known When I Survey the Wondrous Cross are introduced by a high soprano solo — “emphasizing, I hope, the tender and compassionate nature of the text rather than the revivalist ardor and stridency of some others of Watts’ hymns.”

Also, the poem that lends its title to the whole piece, Invictus, is by a man, William Ernest Henley. This piece, Goodall explained, was “written whilst suffering unspeakable agonies in one of his extended periods in hospital. Henley married one of the nurses who tended him in hospital in Edinburgh; their daughter Margaret, who tragically died aged 5, was the real-life inspiration for J.M. Barrie’s Wendy in Peter Pan.”

The connection he found with Henley’s words is compassion. Much of this new choral work “is prompted by the desire to evoke in music the concept of compassion, caritas, the unselfish care for others, a role overwhelmingly played in human history by women,” he said.

In a composer’s note about the piece — written two years before COVID-19 ravaged the world — Goodall said: “The recurring messages of this collection — suffering, fortitude, compassion and survival against terrible odds — are intended to challenge and comfort in equal measure. We live in a troubled era, one at times saturated with conflict, hazard and anger. I have tried to find a musical vocabulary for the piece which creates layers, therefore, without muddying understanding.”

In a composer’s note about the piece — written two years before COVID-19 ravaged the world — Goodall said: “The recurring messages of this collection — suffering, fortitude, compassion and survival against terrible odds — are intended to challenge and comfort in equal measure. We live in a troubled era, one at times saturated with conflict, hazard and anger. I have tried to find a musical vocabulary for the piece which creates layers, therefore, without muddying understanding.”

Musically, that means the piece begins with two quartets of soloists singing antiphonally. Then a lone soprano saxophone, “the nearest to my mind that a wind instrument gets to the sound of human keening, weaves amongst the voices, at times friendlessly isolated.”

The point, Goodall explained, is to set a “relatively sparse, personal, almost baroque texture” where “the voices are paramount, allowing those of the authors and poets to speak directly and urgently to us.”