Since becoming king of the Benin kingdom in southern Nigeria, Eheneden Erediauwa has embarked on a vigorous campaign to retrieve many of the kingdom’s artworks, lost or looted from the royal palace over the past century and a half, and seen displayed in museums across the world.

That effort now has reached the Smithsonian, one of the most prestigious of all American museums, and reignited a conversation about the ethics of institutions retaining works of art that were looted or stolen on their way to them — even if they weren’t the ones who stole them.

Oba of Benin

Erediauwa is also known in Nigeria as Ewuare II but reverently addressed as the Oba of Benin. He is working in alliance with Nigerian federal authorities and the National Commission for Museums and Monuments on the effort to return stolen art.

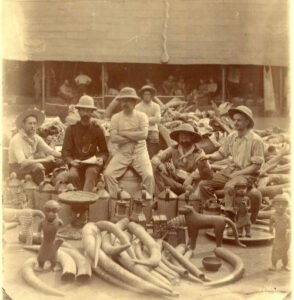

It was another Oba of Benin — Ovonramwen Nogbaisi — whose palace was looted by British forces in 1897. The British burned the Oba’s palace to the ground and forced the monarch into exile as reprisal for the killing of British officials by some Benin natives.

Among the art carried off was dozens of Benin Bronzes, a term today used to describe artifacts ranging from brass plaques, carved elephant tusks, ivory leopard statues and wooden heads. The objects include a group of elaborately decorated casts created from at least the 16th century onward in the West African Kingdom of Benin by specialist guilds.

Many of these pieces were commissioned for the ancestral altars of past Obas and Queen Mothers. They also were used in other rituals to honor ancestors.

The Smithsonian has 39 Benin Bronzes it plans to return to Nigeria’s ownership — although some of the works could remain on display in the United State on loan from the Nigerian people.

This will be the first repatriation under the Smithsonian’s new policy of “ethical returns,” according to Linda St. Thomas, spokesperson for the Smithsonian Institution.

British soldiers with objects looted from the royal palace during the military expedition to Benin City in 1897.

Among the countless artifacts and art pieces taken from Nigeria, none elicits as much discussion or passion as the Benin Bronzes.

Asked to name the artistic or financial value of the artworks, St. Thomas replied: “We don’t put monetary value to the 155 million objects in the Smithsonian collections. But it is clear that the Benin Bronzes are of great historical significance.”

Not only do the pieces represent Nigerian history, they now are part of global history. The looting happened about two decades prior to the 1914 creation of what is today Nigeria. The modern nation was created through the amalgamation of southern and northern protectorates of the geographical sphere by British officer Lord Lugard.

That bloody history has shaped the conversation with museums like the Smithsonian about whether to keep the contested works or to return them to their original homes. St. Thomas said the Smithsonian has not yet finalized its collections policy for works with contested ownership. The institution’s board of directors will take that up in April. And although returning the Benin Bronzes must be approved by the board, “certainly they will be the first artifacts under consideration,” she explained.

For many Benin natives, and particularly the royal palace, the return of their artworks is a necessary but small recompense for the crimes committed against their people.

Those crimes, however, did nothing to tame their artistry in bronze making. The natives emerged from the ruins of 1897 to rebuild their homeland, asserting their skills in sculpture-making, which remains their greatest export.

As part of efforts to preserve the Benin cultural heritage, Nigeria’s Edo State government last year unveiled plans to build a facility called the Edo Museum of West African Arts, where many of the returned artworks are to be displayed.

“In this plan, we have included the carving out of a large area as a cultural district and the museum will be located in the cultural district,” said Godwin Obaseki, Edo State governor. “If we host 5,000 visitors every year as a result of the attraction to the museum, the state will benefit from it.”

A sculpture from the mid-16th to 17th century depicting warriors that is among the Benin Bronzes held by the Smithsonian. (Photo: Franko Khoury/National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution)

The new museum will be part of the national museum complex and home of the most comprehensive display of the Benin art collection anywhere in the world. It also will house a research institution.

“The artworks are global works and represent Africa, Nigeria and Edo globally; we should not lose them,” Obaseki said. “We insist on the return of these artifacts to their original home, Benin City.”

Some of the Benin artifacts already have been returned from Germany, the United Kingdom, Mexico, the Netherlands, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York City.

Babatunde Adebiyi, legal adviser to Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments, said 29 of the 39 Benin Bronzes now held by the Smithsonian are expected to be returned to the country.

Additional items are slated to arrive soon from Glasgow, Scotland; the U.S. National Gallery of Arts; Pitt River Museum of the Oxford University; the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of Cambridge University; the Great North Museum of Newcastle University; and Rhode Island School.

A more complete history of the Benin Bronzes is available online from The British Museum.

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who currently lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.