On Thursday evening, church bells began to chime in Oxford, where I am living for much of this fall while on research leave from Baylor University. I’d planned a long writing day, but I simply sat, my front door open, listening to the bells from St. Giles Church around the corner as the evening grew dark and cool, overhearing the hushed voices of those on the street as they spoke of the passing of Queen Elizabeth II.

I felt a surprising sadness and so began working to unpack that. I was still working when I left for Wales to spend the weekend with my friends Rowan and Jane Williams. Our conversations about the queen’s life and legacy complicated my thinking and began to spark insights, as indeed every conversation with Rowan does.

Greg Garrett with Rowan Williams

Rowan, who is the past Archbishop of Wales and then of Canterbury, knew the queen perhaps as well as anyone outside her family. Although he, too, is a staunch progressive and democratic thinker, the queen had hosted Jane and him at her Sandringham estate, and he officiated at the royal wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton. For as long as I have known Rowan, he has displayed a set of signed photos of the queen and Prince Philip, first in the drawing room at Lambeth Palace in London, then for some years, in Cambridge in the guest room where I used to sleep when I visited him at Magdalene College in Cambridge. (I used to turn the queen face-down on the table at night so she wouldn’t watch me as I slept; again, please remember, I am not a royalist.)

On this latest visit to Cardiff, as Rowan reminisced about Elizabeth, those same photos looked down from the top shelf of the bookcase, and while I suspect he also thinks of the monarchy as an institution whose time has come and gone, he could not help shaking his head in admiration for her long years of sacrifice, could not help smiling ruefully as he recalled how genuinely funny she was out of earshot of the press or the public.

“American Christians have displayed a multitude of reactions to the death of the queen, but most interesting to me has been how many conservative evangelicals have lamented her death.”

American Christians have displayed a multitude of reactions to the death of the queen, but most interesting to me has been how many conservative evangelicals have lamented her death, their comments about her in some cases bordering on the reverential. My quest to unpack my own feelings led me to reflect on theirs as well.

I am often guided by something the Black theologian Kelly Brown Douglas says about films on race that we screen and discuss: “Why do you suppose a white audience needed this?” This question seems to weigh heavily on the queen’s death as well.

It is possible to read the Bible badly, to read it in a way that dishonors its central truths. It is also possible to misread a symbol like the reign of Elizabeth Regina. I’d like to examine two possible misreadings that seem shaped by cultural and political movements currently afoot among white Christians, and then offer a third that might hew closer to the message of that Jesus who, as Rowan says, redeemed us and will not abandon us.

It is possible to read the Bible badly, to read it in a way that dishonors its central truths. It is also possible to misread a symbol like the reign of Elizabeth Regina. I’d like to examine two possible misreadings that seem shaped by cultural and political movements currently afoot among white Christians, and then offer a third that might hew closer to the message of that Jesus who, as Rowan says, redeemed us and will not abandon us.

Some conservative Christian celebrations of the queen seem to park her firmly in the camp of traditional womanhood and quiet dignity. On his Facebook page, Franklin Graham cited his father, Billy’s, description of the queen as “a woman of rare modesty and character.” On his Twitter feed, Owen Strachan, former president of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, declared “What an example of decorum, duty, dedication to traditional principles, toughness, womanhood, and British classiness.” Al Mohler spoke of her as a figure who stood against creeping immorality and liberalization, that seeming “moral convulsion” against which so many culture warriors are arming: “not only the issue of divorce, but premarital sex, abortion, homosexuality, the entire LGBTQ spectrum of issues, but … also the general liberalization that came home in Elizabeth’s own family.”

“In these readings of the queen’s life, she was a person ‘like us’: that is white, Christian, moral, culturally and perhaps otherwise conservative.”

In these readings of the queen’s life, she was a person “like us”: that is white, Christian, moral, culturally and perhaps otherwise conservative. Broadcaster Dana Loesch tweeted her on-air reaction regretting the passing of “the unwoke Christian Queen of England.” Unlike my friends Kristin du Mez and Beth Allison Barr who spend their days vocally combating complementarianism and male religious thuggery, Elizabeth famously did not publicly comment on matters of the day, whether moral or political, and thus it’s possible that white male figures in the evangelical church could imagine that Elizabeth agreed with them, although she probably did not. Hearing Rowan Williams talk about the queen’s arch sense of humor and sarcastic wit suggests she was much more in Beth and Kristin’s camp, a woman very aware of her gifts, intelligence and the absurdity and even danger of male obsessions with power.

Still, reading many of these commenters, it seems their reverence for the queen allows them to freeze the image of womanhood in the 1950s, when Elizabeth assumed her crown. Even this powerful woman — the Queen of England! — did not speak out of turn or contradict her betters (that is, the men, who counseled and actually ran the country). Perhaps none of these guys have watched The Crown, where Matt Smith’s Prince Philip complains that he doesn’t know if Elizabeth is his queen or his wife. Elizabeth (Claire Foy) tells him, “I am both, and a strong man would be able to kneel to both!”

Still, reading many of these commenters, it seems their reverence for the queen allows them to freeze the image of womanhood in the 1950s, when Elizabeth assumed her crown. Even this powerful woman — the Queen of England! — did not speak out of turn or contradict her betters (that is, the men, who counseled and actually ran the country). Perhaps none of these guys have watched The Crown, where Matt Smith’s Prince Philip complains that he doesn’t know if Elizabeth is his queen or his wife. Elizabeth (Claire Foy) tells him, “I am both, and a strong man would be able to kneel to both!”

“It seems their reverence for the queen allows them to freeze the image of womanhood in the 1950s, when Elizabeth assumed her crown.”

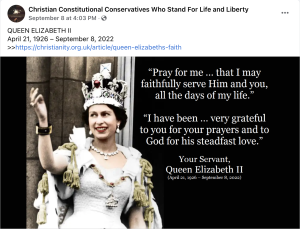

In addition to this complementarian queen some evangelicals imagine aligning with their own views of Christian womanhood, others have leaned into her power, authority and Christian faith. Again, imagining that she was a person “like us,” it becomes possible to validate the recent drive of American Christians to unite Christian faith and political power.

Mohler in his podcast speaks of the inherent authority lent by a hereditary monarchy as well as of her faith as an anchor against anarchy. In recent years, evangelicals have supported a demogogue who sought to rule instead of govern and got their heads around that because it was, to use Kelly Brown Douglas’ words, the story they needed to hear.

Dana Loesch retweeted an image of the queen firing an assault rifle on the firing range from Brandon Morse, who recently has tweeted a number of militaristic and even fascistic images of the queen drawn from her long reign.

In this reading, the queen, who was indeed deeply religious and who at least symbolically ruled for 70 years, could — in a bad reading — stand in as a figure of the explicitly Christian reign that many American evangelicals seem to be seeking. As the Center for Religion and Civic Culture notes, white Christian nationalists “are currently using state power to impose their will on others”; one has only to open a browser or turn on the news to see evidence. Or to listen for a hot minute to Sen. Josh Hawley, who announces the agenda: “We are called to take that message into every sphere of life that we touch, including the political realm. … That is our charge. To take the lordship of Christ, that message, into the public realm, and to seek the obedience of the nations. Of our nation!”

In this reading, the queen, who was indeed deeply religious and who at least symbolically ruled for 70 years, could — in a bad reading — stand in as a figure of the explicitly Christian reign that many American evangelicals seem to be seeking. As the Center for Religion and Civic Culture notes, white Christian nationalists “are currently using state power to impose their will on others”; one has only to open a browser or turn on the news to see evidence. Or to listen for a hot minute to Sen. Josh Hawley, who announces the agenda: “We are called to take that message into every sphere of life that we touch, including the political realm. … That is our charge. To take the lordship of Christ, that message, into the public realm, and to seek the obedience of the nations. Of our nation!”

Listening to Rowan Williams preach Sunday in a tiny church in Wales, though, I heard a faithful alternative to these cooptings of the figure of Queen Elizabeth. The Gospel reading was about the lost sheep and the lost coin. Lord Williams reminded us in his sermon — all 20 of us — that in God’s economy, everyone is worth seeking and finding. That the loss of any of us is tragic and to be avoided at all costs. “No one is disposable or dispensable,” he said.

“It is not a pale faithful remnant, but the whole rainbow world that Jesus loves.”

This is, first, as far from a white Christian nationalist understanding as can be found. It is not a pale faithful remnant, but the whole rainbow world that Jesus loves. But then in leaning into one of the Christian faith’s oldest understandings of Jesus as the Good Shepherd, Rowan reminded us that power rightly used is not about domination; it is about finding, feeding, caring. How in her decades of very public care for her nation, Elizabeth was offering an example of sacrifice from which all of us could learn.

As a devout Christian, Elizabeth accepted this task as her vocation; she understood this to be the lifelong work to which God had called her. Her ministry, if you will, since all of us are called to serve God and each other, not just white guys in positions of Christian authority.

Truth? I probably still would turn a picture of the queen facedown if circumstances dictated. But after hearing one of the wisest people I know reflecting on the queen’s life and legacy, I feel it’s necessary to speak out like my braver friends: Queen Elizabeth was not a modest hausfrau, nor was she a Christian militant. She was a strong, faithful and intelligent leader who probably rose from her deathbed to perform one final act for the nation, that meeting with new Prime Minister Liz Truss.

Truth? I probably still would turn a picture of the queen facedown if circumstances dictated. But after hearing one of the wisest people I know reflecting on the queen’s life and legacy, I feel it’s necessary to speak out like my braver friends: Queen Elizabeth was not a modest hausfrau, nor was she a Christian militant. She was a strong, faithful and intelligent leader who probably rose from her deathbed to perform one final act for the nation, that meeting with new Prime Minister Liz Truss.

I probably never will be a royalist. But I can and will offer prayers for the soul of Elizabeth the queen and join my friend Rowan in celebrating her as a remarkable Christian woman.

That story is the one I need.

Greg Garrett is Carole McDaniel Hanks Professor of Literature and Culture at Baylor University and canon theologian for The American Cathedral in Paris. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and canon theologian at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Buttrick and Buechner in the balcony of heaven | Opinion by Stephen Shoemaker

Reimagining the ‘kingdom’ of God as something other than an ancient hierarchy | Opinion by Rick Pidcock