“We are facing an unprecedented global food crisis, and all signs suggest we have not yet seen the worst. For the last three years hunger numbers have repeatedly hit new peaks. Let me be clear: Things can and will get worse unless there is a large-scale and coordinated effort to address the root causes of this crisis. We cannot have another year of record hunger.”

This is the warning of David Beasley, executive director of the World Food Program.

Nowhere globally is the hunger crisis more severe than in Africa. Over recent years, a combination of factors including COVID-19, conflict and insurgency, harsh climatic conditions and the war in Ukraine have combined to worsen the hunger situation on the continent.

The 2022 Global Hunger Index released in October found eight out of the 10 countries described as the “hungriest” places in the world are located in Africa. The Global Hunger Index was published by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe. Among the eight listed African countries are Central African Republic, Madagascar, Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, Niger, Liberia, Lesotho, and Sierra Leone.

According to the organizers, the Global Hunger Index “is a tool designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger at global, regional and national levels, reflecting multiple dimensions of hunger over time.”

The aim is to “raise awareness and understanding of the struggle against hunger, provide a way to compare levels of hunger between countries and regions, and call attention to those areas of the world where hunger levels are highest and where the need for additional efforts to eliminate hunger is greatest.”

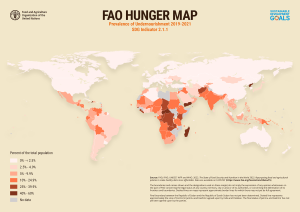

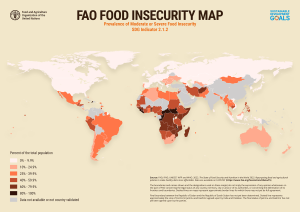

“While most of the world’s undernourished people live in Asia, Africa is the region where the prevalence is highest.”

A report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations states: “In 2021, hunger affected 278 million people in Africa, 425 million in Asia and 56.5 million in Latin America and the Caribbean — 20.2%, 9.1% and 8.6% of the population, respectively. While most of the world’s undernourished people live in Asia, Africa is the region where the prevalence is highest.”

It adds that “after increasing from 2019 to 2020 in most of Africa, Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean, hunger continued to rise in most subregions in 2021, but at a slower pace. Compared with 2019, the largest increase was observed in Africa, both in terms of percentage and number of people.”

Other research by the Africa Union in collaboration with the World Food Program shows the level of hunger and undernourishment in Africa amid economic challenges: “Over the past few years, the increase in global food prices, followed by the economic and financial crisis, have pushed more people into poverty, vulnerability and hunger. Even though the number of undernourished people has fallen globally by 13.2% from 1 billion to 868 million in the last 20 years Africa’s share in the world’s undernourished population has decreased from 35.5% in 1990 to 22% in 2019.

However, this alarming rate still calls for stronger efforts to improve food security and nutrition in the continent,” it states, adding that “stunting among children under the age of five remains a key challenge in Africa. According to the World Health Organization classification of assessing severity of malnutrition, half of African Member States have high to very high (over 30%) prevalence of childhood stunting….”

Among the multiplicity of factors behind the hunger index in Africa is harsh climatic conditions such as drought that impacts food production. The drought, in turn, is part of the reason farmer/herder clashes are rampant across Africa as herdsmen in search of scarce grazing areas often meet with resistance from farmers keen to preserve their crops.

Clashes between the two have led to countless deaths over the past years and created a shortfall in crop production and supply.

Then, climate change-induced drought and flooding have created massive problems in countries such as Chad, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Mali, Niger and Cameroon. Devastating floods have inundated farmlands, displaced farmers and killed many people.

According to the U.N.: “The climate crisis is destroying livelihoods, disrupting food security, aggravating conflicts over scarce resources and driving displacement. More than 1.3 million people have been displaced so far in Nigeria, and 2.8 million have been impacted by flooding, with farmlands and roads submerged. In Central Sahel countries — Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso — above-average rains and flooding have killed hundreds, displaced thousands, and decimated over 1 million hectares of cropland.”

Other causes of hunger and food shortages are regional insecurity, violence linked to Islamic militants that keeps farmers away from their farms, and the fallout of the Russian invasion of Ukraine that has led to a rise in the price of petroleum products, wheat and other commodities.

Inflation in many African countries has made food supplies beyond the reach of a significant percentage of people. A recent survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics found 113 million Nigerians, in a population of about 216 million, are classified as “poor.”

Ghana’s president, Nana Akufo-Addo, recently said the challenges are dire: “We are in a crisis; I do not exaggerate when I say so. I cannot find an example in history when so many malevolent forces have come together at the same time.”

Related articles:

In Africa, inflation and a food crisis threaten not just the economy but people’s lives

Nowhere near the war zone, Africans feel the heat of the Russia-Ukraine war in their pocketbooks