On July 4, 2007, our daughter Stephanie and I accompanied James Dunn to Old Salem Village, a site established by Moravians in 1753 in an area south of what is now downtown Winston-Salem. We went to hear our Wake Forest University colleague, the Moravian historian Craig Atwood, read the Declaration of Independence where it has been read every Fourth of July since 1783.

On July 4, 2007, our daughter Stephanie and I accompanied James Dunn to Old Salem Village, a site established by Moravians in 1753 in an area south of what is now downtown Winston-Salem. We went to hear our Wake Forest University colleague, the Moravian historian Craig Atwood, read the Declaration of Independence where it has been read every Fourth of July since 1783.

We neglected to take folding chairs so the three of us leaned against the white picket fence that borders Old Salem square. The event came during a “troop surge” in the 4th year of the Iraq war and the presidency of George W. Bush. Atwood moved eloquently through the revered document, then came to the Declaration’s list of grievances against the English king, George III:

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount, and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people. . .

As Atwood read each sentence, James Dunn answered back, a July-4-Baptist-call-and-response: “Yes he has!” “Uh huh!” “Oh yes he did!” Dunn didn’t mean the king of England; he meant the president of the United States!

“Whatever else Dunn continues to teach us about life and faith, it is inseparable from the Jesus story.”

People in the crowd looked around to see who was answering the Declaration, some frowning at Dunn, Stephanie and me. James, of course, was undeterred. It was the 4th of July, by George, and he let his freedom of dissent ring.

I finally said, “James, if you don’t quiet down, even the peaceful Moravians are going to throw us out of here!” James didn’t quiet down; and the Moravians didn’t ask us to leave.

Oh, freedom. Freedom over all of us that 4th of July 2007. But I wonder: What would James have said out loud last week on July 4, 2019?

James Milton Dunn died of heart failure on July 4, 2015, less than a month after his 83rd birthday. An ordained Baptist minister, Dunn’s sense of vocation took him into a variety of settings as pastor, campus minister, Executive Director of the Texas Baptist Christian Life Commission, Executive Director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (BJC) and Resident Professor at Wake Forest’s School of Divinity. In all those locales, where justice and religious liberty were at stake, James Dunn would not keep silent.

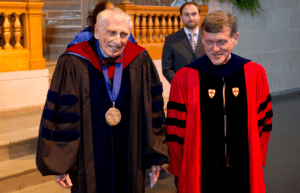

James Dunn and Bill Leonard following a Wake Forest University convocation service in 2012. Photo courtesy of Bill Leonard.

Aaron Weaver’s book, James M. Dunn and Soul Freedom (2011), documents Dunn’s life and thought in all their prophetic, pastoral and iconoclastic vigor. In the introduction, PBS journalist Bill Moyers, one of Dunn’s closest friends, commented: “In the long tradition of religious liberty in America . . . Dunn has carried a steady flame as both a believer and patriot. He is unique in our time for his courageous opposition to the politicizing of religion and for his many battles in defense of individual conscience.”

In the same volume, Baptist historian Walter Shurden noted that, “Dunn, whose cornbread and pot ‘likker’ persona masked a universe of biblical, theological, ethical, and denominational sophistication, is one of the most important Baptists in America for the last fifty years.” I would echo that assessment and add that Dunn’s deepest commitments were to Jesus Christ, his beloved spouse Marilyn McNeely Dunn, Baptist ways of being the church, a ceaseless struggle for religious liberty, his Texas heritage and the Democratic Party – all in that order, except on Election Day!

Audaciously outspoken, Dunn’s abiding love and care for persons was equally legendary. Reflecting on Dunn’s life, Jorene Taylor Swift, a minister at Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, wrote: “We loved James for many reasons – I was proud of him because he said things we all want to say and he said them in such a pithy, direct way – he was our own Baptist folk hero and probably the most important – once he met us he never forgot our names.” When James Dunn was one-on-one with you, it was like you were the only person in the world. North Carolina Council of Churches leader George Reed said that Dunn “probably left more people with more memories than anyone else I’ve known.” No argument there.

“Dunn would have no patience with those who continue to insist that America is a ‘Christian nation,’ a historic and gospel heresy from the beginning of the Republic.”

Four years after his death, Dunn’s theological, ethical and political insights; his fearless candor, steeped in a Christian faith uncoerced by government or religious establishments; and his forthright advocacy of freedom of conscience in the church and the public square prompt some folks (including me), to ask: In this era of political turmoil and ecclesiastical identity crisis, WWJDD – What Would James Dunn Do? That question led David Wilkinson, executive director and publisher at Baptist News Global, to invite me on the eve of this year’s July 4th celebration – shoved into political and partisan territory by President Donald Trump – to reflect on a response. I agreed, with fear and trembling.

Fortunately, Weaver also edited a collection of Dunn’s articles, addresses and sermons in a text entitled A Baptist Vision of Religious Liberty & Free and Faithful Politics: the words and writings of James M. Dunn (2018). My speculations on Dunn’s response to the current religio-political scene are drawn from Dunn’s written reactions to related issues during his tenure of Baptist leadership.

First, whatever else Dunn continues to teach us about life and faith, especially in the public square, it is inseparable from the Jesus story.

Throughout his life, Dunn was haunted by Jesus, who he was, what he taught and the implications of Jesus’ most basic message: “The kingdom of God (God’s New Day) has come near you.” Moyers wrote of Dunn: “Like his mentors, J.M. Dawson and T. B. Maston, the mystery of the Christ event has been central to James’ understanding of his faith and practice. The encounter occurred early on and it transformed him, producing a principled commitment to action and aware[ness] at every turn of that transcendent Presence.”

It was Jesus who claimed James, and James who claimed Jesus. Indeed, one of his most famous declarations – “Ain’t nobody gonna tell me what to believe except Jesus” – got him into considerable trouble with folks right and left of center. For Dunn, that statement and its accompanying theology was neither glib platitude nor quirky individualism, but a heart-driven confession grounded in the power of uncoerced faith and the transforming community of God’s New Day in the world.

Second, doubtless it is the Jesus story to which Dunn would have us depend in this specific moment in the life of America’s churches.

He would warn us not to blame secularism or religious indifference for impacting current declines in church attendance, membership, finances and social privilege without first giving serious attention to ways in which churches themselves contribute to declines and indifference. Amid such realities, churches should not expect the state to prop them up with new favors or privilege.

In a 1991 essay in the BJC’s Report from the Capital, Dunn wrote that a church that maintains so close “a partnership with government that one cannot tell when worship leaves off and patriotism begins has slipped into idolatry.” Lacking that “healthy distance. . . the prophetic vision is blurred, the witness is muffled, and the gospel compromised.” He added that “when the church’s mission is tinted, tainted, or tailored by the state, she ceased to be the bride of Christ and has fallen into an incestuous bed of cultural captivity,” warning that “too many Christians have been willing to let public institutions do too much of the church’s job.”

Third, now more than ever, Dunn would encourage Christians to become politically engaged, especially given his own Baptist heritage of dissent in the public square.

In 1984 he wrote, in words that seem equally applicable to 2019: “We see in the United States today a deliberate attempt to collapse the distinction between mixing politics and religion (which is inevitable) and merging church and state (which is inexcusable).” From his perspective, “Not to take a stand in the political context is to support the status quo…. To fail to alarm another morally assures that one will remain morally asleep . . .”

Fourth, these days, Dunn would bring down considerable wrath on those religious and political figures who denounce the free press as “enemies of the people,” labeling their reports as “fake news,” while themselves unable to tell the truth to the American people.

In another 1984 essay (an ironic year to be writing on this topic), Dunn declared: “If freedom of religion offers the profound theological base for the American experiment, freedom of the press proves that we mean business…. We live in a day when those at the highest levels of government seem to fear truth-telling. They try to restrict the truth-tellers or ridicule them as being guilty of ‘leaks.’”

“Dunn would surely be a leading voice in denouncing the government’s inhumane treatment of immigrant children on the border of his beloved Texas.”

He concluded: “A heavy-handed government, whether exercising censorship on writers or prescribing religion for the public schools, is the enemy of freedom.”

Fifth, Dunn would have no patience with those who continue to insist that America is a “Christian nation,” a historic and gospel heresy from the beginning of the Republic.

Like Roger Williams before him, Dunn declared that there are no “Christian nations,” only Christian people, bound to Christ by faith, not citizenship. Dunn said it straight up: “The trouble with a theocracy is that everyone wants to be Theo!” Likewise, he would reject the growing clamor that Christians should reject movements for “social justice,” writing, “The Christian who denies the social dimension of the gospel is putting a premium on ignorance, resting on an immoral nostalgia for things once learned, and modeling mediocrity.”

Dunn would surely be a leading voice in denouncing the government’s inhumane treatment of immigrant children on the border of his beloved Texas – and the preachers who have steadfastly defended those cruel actions.

Like his dissenting Baptist forebears, Dunn simply gave a witness, whatever the outcomes might be.

I will never forget the day (January 19, 2001) when I was sitting in my office at Wake Forest University watching my colleague and friend testify at the cabinet appointment hearings for John Ashcroft to be attorney general of the United States. Dunn’s name appeared at the bottom of the screen, as did the words “Wake Forest University.”

Dunn testifies at a congressional hearing. Photo/BJC.

“O God,” I said out loud (in this instance, a prayer rather than an oath). Minutes later the phone rang. A voice on the other end asked, “Does this man who’s testifying against Mr. Ashcroft work at Wake Forest?”

Yes, I replied. “Well,” she continued, “he’s criticizing a fine Christian. Can you stop him?”

“No, ma’am,” I answered. “I’m just the dean; you’d have to talk with Jesus if you want to stop him.”

“You’re no better than he is!” she declared, and hung up.

I’ve never received a better compliment.

Today, as the Trump administration promotes government aid to parochial schools, redefines elements of church/state separation and even politicizes, militarizes and reorients a previously nonpartisan celebration of American independence, would Dunn have kept silent? Never!

Dunn taught us to follow Jesus, voicing grace and dissent when justice and conscience require. Reverend Abigail Pratt, then a student in the religion and public policy class taught by Dunn and Melissa Rogers at the Wake Forest School of Divinity, summed it up well: “Thank you, Dr. Dunn, for the smiles and laughs, for supporting us as young ministers, for advocating for women in ministry, for fighting for religious freedom, for always raising hell when there was hell to be raised (and even when there might not have been).”

At this moment in the history of American Christianity and American government, gospel dissent – sometimes in the form of “raising hell” for conscience’s sake – won’t come easy. It didn’t for James Dunn. Jesus either, BTW.

Related opinion article:

Wendell Griffen | On July 4, I will not be celebrating. Here’s why