As dire as the global climate crisis is, human action to mitigate disaster actually has made the future less bad than it would have been, according to one of the world’s foremost climate scientists — who also happens to be a devout Christian.

Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist at the Nature Conservancy and professor at Texas Tech University, not only is a Christian but is married to a pastor. She embodies on the global stage a way to hold faith and science together, melding both spiritual hope with academic rigor.

In a recent Twitter thread addressing the climate crisis, Hayhoe emphasized the real dangers of climate change and the seriousness of this issue for everyone. At the same time, she offered some optimistic advice on how global warming can be slowed.

And for the sake of skeptics — 37% of white evangelicals believe there is no evidence to support climate change — she explains how the mitigating work already done has made a difference.

Holding the line

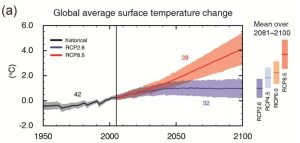

She began the thread with a graph showing global average surface temperature change, noting that “less than 20 years ago, the world was headed for a >4C” increase in temperature. This rate of change would have created an unsurvivable environment for humans.

After this, she offers a brief explanation of why this rate of change has been reduced, emphasizing the human role in climate change, and the world’s collective effort to “hold the increase in global temperature to 2C” and work toward limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Currently, according to a United Nations analysis Hayhoe links to in her thread, the U.N. Environment Program predicts the world is “on track for a temperature rise of between 2.4C and 2.6C by the end of this century,” but that “only a 45% emissions reduction will limit global warming to 1.5C.”

“We have significantly reduced the projected rate of warming but have not attained our goal of holding the temperature change to needed levels.”

What does that mean? We have significantly reduced the projected rate of warming but have not attained our goal of holding the temperature change to needed levels. However, the evidence now proves that further reductions in temperature change are still possible if essential and rapid changes are made.

Three solutions

How to do this? Hayhoe gives three solutions.

First, focus on reducing emissions. The temperature increase never will be lowered to 1.5C without this. Hayhoe says this is attainable by accelerating the transition to clean energy sources, preventing deforestation and reforming food systems.

Second, identify where in the atmosphere there is too much carbon and remove it. This carbon can then go “back into our soils, ecosystems and fields through nature-based solutions” that utilize up to 37% of the carbon produced by humans.

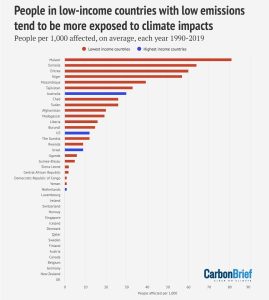

Third, because there are impacts of climate change that no longer can be avoided, the world must adapt. And the word “we” is important here: Hayhoe explains that the impacts of climate change disproportionately affect “those who have done the least to cause the problem.”

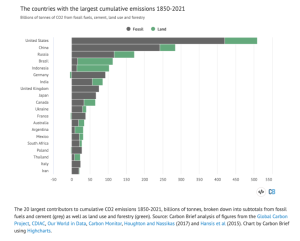

She then shows two graphs, one that compares countries with the largest cumulative emissions, the U.S. being the highest, and another that shows what countries are most affected, broken down by low- vs. high-income nations. These graphs show that countries with the highest emissions are typically the least affected, while many of the countries most affected by climate change are low-income and do not contribute to major amounts of global emissions.

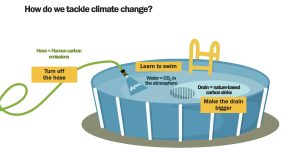

Nearing the end of her thread, she offers readers a simple metaphor.

Showing a diagram of a swimming pool, she says, “We need to turn off the hose as fast as we can, enlarge the drain at all speed, all while learning how to swim” and helping “others learn as well.” In other words, we need to quickly reduce carbon emissions, adapt to irreversible climate impacts and drain extra carbon back into nature systems that can use it.

This is a hopeful view of climate change and one that calls on humans to take action to create a better, more liveable future. However, not everyone is so optimistic.

Carbon emissions are still rising

An article by the Economist titled The World Is Going to Miss the Totemic 1.5C Climate Target, offers less hopeful projections. This briefing offers readers a history of the 1.5C goal, which stems from the Paris Climate Summit in 2015 where the goal was a “red-line item” for many countries, including the Caribbean states who were prepared to walk away from negotiations if they found the goal would not be included in the Paris Agreement.

Although many countries have pledged to make changes (and some have made progress) in an effort to fight climate change, carbon emissions are still rising, and the article states that “this year, as the climate world meets in Sharm el-Sheikh on the Red Sea for cop27, hosted by Egypt, it would be far better to acknowledge that 1.5 is dead.”

According to the Economist, this is because “an emissions pathway with a 50/50 chance of meeting the 1.5°C goal was only just credible at the time of Paris. Seven intervening years of rising emissions mean such pathways are now firmly in the realm of the incredible.”

The magazine explains that temperature projections have been made under the assumption that the world will commit to “negative emissions,” meaning removing carbon from the atmosphere. This is the “drain” Hayhoe talks about in her thread.

“To reach our goal, we actually have to put in the work, which does seem to be happening fast enough.”

These negative emissions would allow the carbon budget to be overspent. The problem with utilizing negative emissions to balance projections is, if we do not make the proper emissions cuts and find higher projected temperatures, we can just add more negative emissions into our future plan to make it look nice. However, to reach our goal, we actually have to put in the work, which doesn’t seem to be happening fast enough.

And then there’s public opinion

There are also differing views about climate change among average citizens.

According to data from Pew Research Center, 25% of all U.S. adults believe there is no solid evidence for climate change. Of religiously affiliated adults, when compared to other demographics, white evangelicals are the least likely to believe climate change is caused by human activity (28%), the most likely to believe it is caused by natural patterns (33%), and also the most likely to believe there is no evidence to support climate change (37%).

Of all demographics polled, the groups most likely to believe climate change is caused by human activity are Hispanic Catholics (77%) and unaffiliated persons (64%).

Why are Christians apathetic about climate change? It could be a result of dispensational theology, or beliefs about what we call the “end times.”

A recent journal article published from Cambrige University Press states that “those who believe the biblical end times are near tend to devalue environmental action.”

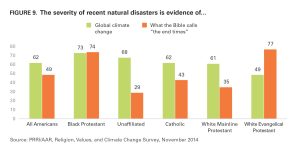

PRRI research backs up this claim in a 2014 study that found some religious Americans believe the severity of recent natural disasters is related to the “end times,” not climate change. These beliefs are especially prevalent among white evangelical protestants (77%), and Black protestants (74%).

There are two schools of thought surrounding dispensational beliefs and climate change. The first is that we must use all the earth’s resources before this “dispensation” is over because that is how God intends us to live. (A dispensation refers to a time period in which God allows something specific to happen; in this case, access to vast amounts of natural resources would be part of our current dispensation.)

The second belief is that the impacts of climate change are signs of the coming end times and cannot be stopped by human intervention.

Other Christians either believe climate change is due to human activity, there is no evidence, or do not have a strong personal opinion on the matter.

Where can hope be found?

How do we balance these differing views? If Hayhoe is hopeful about the 1.5C goal, other climate scientists are not and Christians across the board disagree on the causes and seriousness of climate impacts, what do we do?

Catherine Wright, an ecotheologian holding degrees in both science and religion, embraces both disciplines in her approach to climate.

In a 2017 journal, she called upon believers to embrace an “ecotheological anthropology” as they view the self, their God and the world as intrinsically connected. There are “four primary commitments” believers take on when juggling with this approach, she said: “a grander horizon for eschatological hope; a radical optimism for our interdependent, cosmic web of life; an avowal of a cosmic-numinous communion; and an embrace of the dynamic, unfolding nature of the universe which is necessarily both creative and destructive.”

“If we lack eschatological hope, our care for the world in which we are all intertwined declines.”

In other words, we live in a world in which everyone and everything is interconnected. The ways we care for, or choose not to care for, one another have deep and dynamic implications. The same goes for the ways we interact with our environment. If we lack eschatological hope, our care for the world in which we are all intertwined declines.

Wright goes on to say that an embracing of ecotheological anthropology allows jugglers to pay attention to “both the shadowy and fecund side of our unfolding universe.” Believers will be able to understand the creative yet sacrificial nature of the world, learning how to differentiate between the “inherent finitude and suffering we ought to participate in” and the “inflicted, anthropogenic suffering that can and should be eradicated.”

So, science and religion can go hand in hand in our quest to respond to the environmental crisis of climate change. But, as Hayhoe states, it is essential that we work together to do this. The inflicted suffering we have placed upon the planet by lacking action should be eradicated. And the 1.5C goal may not be entirely plausible, but that does not mean we must give up hope for radical positive change.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves this semester as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

The fantastical world of climate change denial: Slouching toward annihilation | Opinion by Rodney Kennedy

Christians and climate change: A chance to take the Bible seriously | Analysis by Chris Conley

Oregon is burning while most white Christians deny climate science | Opinion by Susan Shaw

National Association of Evangelicals joins call for attention to climate change