Lost amid a contentious presidential election, COVID-19 and Senate confirmation hearings for a Supreme Court justice, the high court opened its new term Oct. 6 by hearing oral arguments in a case about the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Due to the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, the court opened this term with eight justices rather than the more customary nine. If Amy Coney Barrett is confirmed by the Senate, she will join the term already in progress but will have missed arguments in the first cases of the term. And due to the coronavirus threat, the court heard arguments by phone rather than in person.

The RFRA case, Tanzin v. Tanvir, concerns whether the federal religious liberty law passed in 1993 allows three Muslim men to sue FBI agents for money damages. The three allege they were placed on the “no fly” list after they refused to become FBI informants.

Muhammad Tanveer

The plaintiffs are U.S. citizens or green card holders: Muhammad Tanvir, Jameel Algibhah and Naveed Shinwari.

They claim their placement on the “no fly” list was in retaliation for their refusal to become informants against fellow Muslims and therefore violated RFRA. That law prohibits the government from placing a “substantial burden” on an individual’s exercise of religion unless that burden advances a compelling government interest and there is not a less restrictive way to achieve that interest.

As written, RFRA allows people to seek “appropriate relief against a government” for violation of the law. Just what that phrase means is at the heart of the case. First, a federal district court in New York ruled that RFRA does not allow claims for damages against officials who are sued in their personal capacity. On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit reversed that ruling.

BJC joined with the Christian Legal Society and 14 religious liberty scholars to file a friend-of-the-court brief in the case.

Holly Hollman

“The Religious Freedom Restoration Act, like other civil rights laws, is intended to hold government accountable for the protection of fundamental rights,” said BJC General Counsel Holly Hollman. “The Supreme Court should affirm that RFRA was always intended to allow for damages under the same principles that are followed elsewhere in federal law protecting important civil rights.”

Challenge to same-sex marriage

As important as this case is, it did not draw the most attention during the court’s opening week. Instead, most attention was focused not on a case accepted by the court for review but by a case rejected by a majority of the court.

In video footage from the county, Kim Davis is seen asking for the video camera to be turned off as she refuses David Ermold and David Moore (pictured) a marriage license.

As is customary, justices during the first week of the term sifted through hundreds of potential cases to choose the ones they are willing to hear and set aside those they do not want to hear. One case denied a hearing is Davis v. Ermold, which relates to Kim Davis, a Rowan County, Ky., clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, citing her religious beliefs. She did so despite the Supreme Court’s landmark 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges that declared same-sex marriage constitutional.

Subsequently, Davis was defeated in her bid for reelection and sued by two same-sex couples for refusing to issue marriage certificates. Both a trial court and an appeals court rejected Davis’ argument that she is entitled to qualified immunity from monetary damages in civil suits brought against her. Now the Supreme Court has denied a hearing to the case as well.

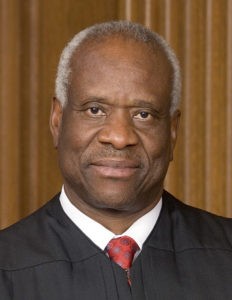

But that’s not the big news. Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito agreed with the court’s denial of Davis’s appeal, but they used the occasion to voice their objections to Obergefell.

“Davis may have been one of the first victims of this court’s cavalier treatment of religion in its Obergefell decision, but she will not be the last,” Thomas wrote. “Due to Obergefell, those with sincerely held religious beliefs concerning marriage will find it increasingly difficult to participate in society without running afoul of Obergefell and its effect on other anti-discrimination laws.”

Clarence Thomas

He added: “It would be one thing if recognition for same-sex marriage had been debated and adopted through the democratic process, with the people deciding not to provide statutory protections for religious liberty under state law. But it is quite another when the court forces that choice upon society through its creation of atextual constitutional rights and its ungenerous interpretation of the Free Exercise Clause, leaving those with religious objections in the lurch.”

Thomas called Obergefell a “ruinous” decision that gave privilege to a “novel constitutional right” instead of the religious liberty interests “explicitly protected in the First Amendment.” He added: “By doing so undemocratically, the court has created a problem that only it can fix.”

Civil liberties groups and LGBTQ advocates expressed outrage at the statement signed by the two conservative justices and saw in it a warning that a more conservative court with three justices named by President Donald Trump could overturn marriage equality.

BJC Executive Director Amanda Tyler saw in the two justices’ comments exaggerated and dire warnings that will only serve to increase the tensions between religious liberty and other important civil rights.

“This hyperbolic statement from Justices Thomas and Alito only makes this tension worse.”

“There are serious and difficult questions about how best to protect religious freedom for all as Americans hold different religious views related to human sexuality,” she said. “But this hyperbolic statement from Justices Thomas and Alito only makes this tension worse.”

Another case already accepted

Before the new term began this month, the high court already had accepted and scheduled another important religious liberty case, which is scheduled for a hearing Nov. 4, the day after the presidential election.

This case goes to the heart of the culture wars fought by the Religious Right for the past four decades: Can religious agencies receiving government funding discriminate on the basis of religion, gender, marital status or sexual orientation?

In Fulton v. Philadelphia, Catholic Social Services challenges the city of Philadelphia’s foster care contracting practices. The city requires agencies that recruit, screen, train and certify foster parents to adhere to the city’s nondiscrimination law, which prohibits agencies from rejecting prospective foster parents based on religion, sexual orientation and other protected categories.

For years, many evangelical faith-based child service agencies have placed various restrictions on who they will work with. Some require foster or adoptive parents to share the agency’s particular religious views, while others focus on household living arrangements that exclude single parents or same-sex couples.

For years, many evangelical faith-based child service agencies have placed various restrictions on who they will work with.

These faith-based agencies — often backed by their parochial donors or denominational bodies — claim the First Amendment’s guarantee of free exercise of religion allows them to discriminate based on their deeply held religious beliefs. The rub comes when agencies cling to those restrictions while accepting government funding or servicing. Critics say that puts government in the role of establishing or supporting one religious belief over another — also a violation of the First Amendment.

This is the heart of the case in Philadelphia, where the city says it has sought to create a level playing field for all agencies that work with foster parents. Because Catholic Social Services would not meet the nondiscrimination requirements of the city, its contract to provide certain foster care services was allowed to expire, even though the city still worked with Catholic Social Services on other issues.

The faith-based agency sued, claiming discrimination by the city. And that, in turn, has set up a monumental case that observers on both sides hope or fear could shift government policy in many other areas where faith-based groups want to set limits on who they will work with and under what terms.

This case has the potential to overturn another controversial Supreme Court ruling called Employment Division v. Smith. Thus, while on the surface the current case is about foster parents, the ripples of this case’s outcome will reach much further into the culture wars.

The plaintiffs in this case paint a dire scenario in their filings with the court, saying the matter involves “urgent issues of national importance.” Catholic Social Services says Philadelphia “offers pro forma arguments, claiming imaginary factual disputes and simply ignoring the precedents that make up the splits on both free exercise and free speech.”

Further, the charity’s filings allege, Philadelphia continues to “exclude Catholic Social Services from foster care while avoiding judicial scrutiny.”

This is an excellent case to revisit Employment Division v. Smith, the charity’s filing asserts, adding: “The Court has known for years that this issue would arise.”