Drive through any city or rural village in the American South and you’ll recognize the buildings. They carry a distinctive appearance even though they may wear slightly different facades like tract housing. But as sure as you can recognize an original McDonald’s or Pizza Hut building, you can spot a Southern Baptist church.

That’s because in the greatest era of growth for Southern Baptists, many of these new and expanding churches turned to the same place for building designs — the Baptist Sunday School Board in Nashville, Tenn.

And that architectural help was driven not by aesthetics — although many of these buildings are attractive — but by the practicality of providing space for age-graded Sunday schools.

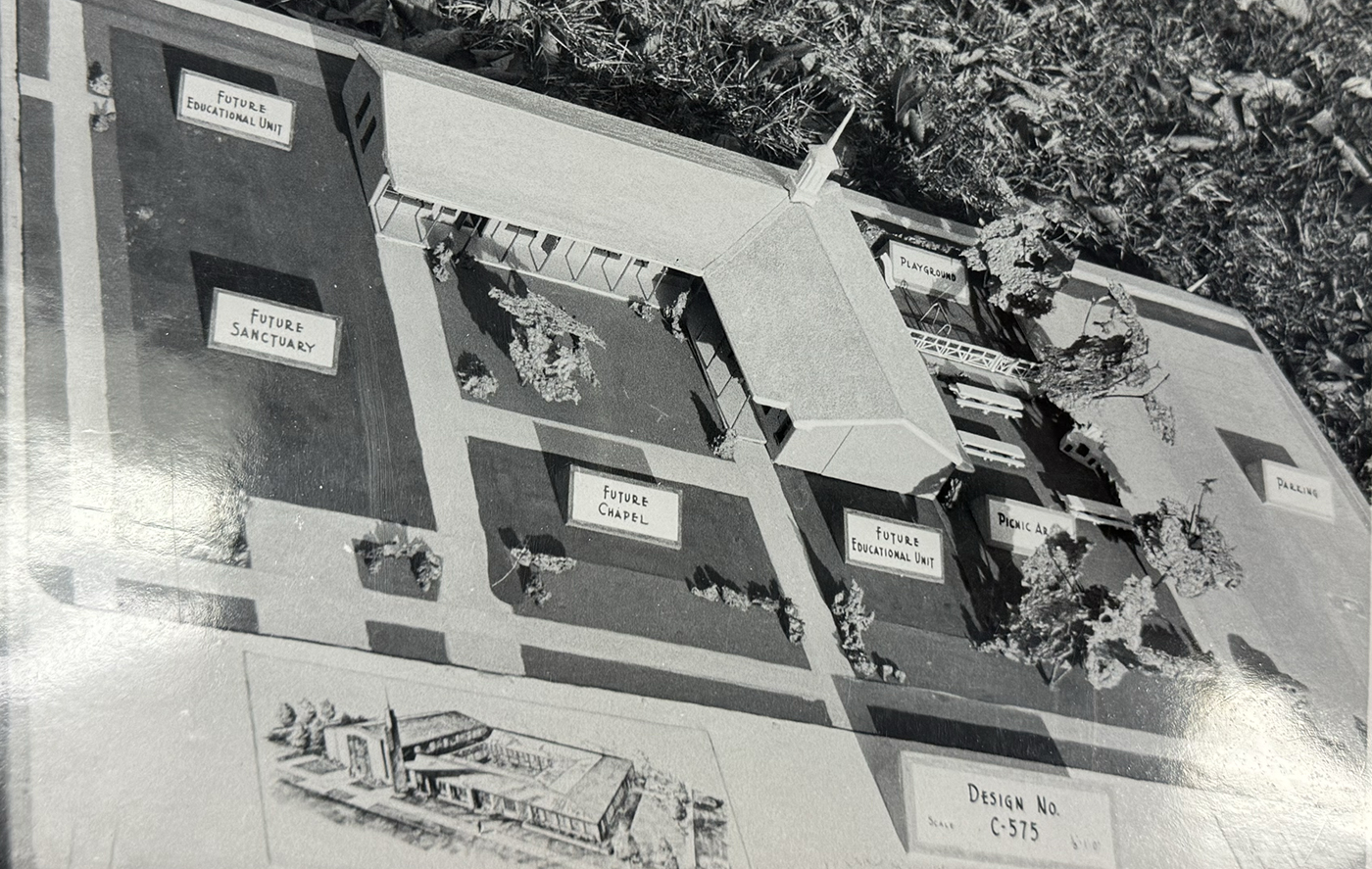

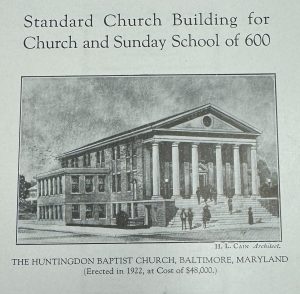

Model of a proposed Southern Baptist church building provided by Baptist Sunday School Board. (Southern Baptist Archives)

Driven by Sunday school

While other denominations placed architectural services in their missions agencies, the Southern Baptist Convention placed its building design services at the Sunday School Board, which had the primary focus of growing church membership and attendance through Sunday school.

To this day, Southern Baptists stand apart from other denominations because of the size and success of their graded education program that gathers people from birth through senior adults into small groups for education and nurture. Doing that right, Sunday School Board leaders said, required the right kind of physical space.

Thus, the Church Architecture Department was born in 1917.

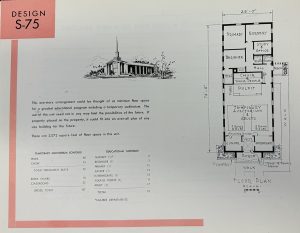

Brochure from Baptist Sunday School Board Church Architecture Department (Southern Baptist Archives)

Although the Great Depression reduced the department to a shell of its origins, the work came roaring back a decade later and grew exponentially as the Baby Boom swept America and new churches were planted and church membership nationwide soared to new heights.

“On a typical Sunday morning in the period from 1955-58, almost half of all Americans were attending church — the highest percentage in U.S. history. During the 1950s, nationwide church membership grew at a faster rate than the population, from 57% of the U.S. population in 1950 to 63.3% in 1960,” according to research by USC Today.

Gallup reports: “U.S. church membership was 73% when Gallup first measured it in 1937 and remained near 70% for the next six decades.”

Among Southern Baptists, this growth was uniquely driven by age-graded Sunday schools and other small-group experiences, such as women’s groups, men’s groups, youth groups and Wednesday night fellowship meals.

These programs required specialized spaces, and the Church Architecture Department offered easy-to-access solutions at little or no cost to Southern Baptist churches. These services could be provided at low cost because the real money-maker for the Sunday School Board was literature — Sunday school curriculum and books. The more Sunday school units that were established, the more curriculum could be sold.

The Sunday School board was giving away razor handles in order to sell more razor blades.

A franchise model

Although Southern Baptist churches never have been franchises like fast-food restaurants — the Baptist doctrine of autonomy of the local church prohibits that — they functioned in the 20th century very much like franchises. Most SBC churches bought all their supplies from the Sunday School Board — everything from Communion cups to Bibles to worship folder covers to music to literature.

Why pay a local architect — who may have no experience with churches — thousands of dollars to draw up building plans when you can get off-the-shelf blueprints from Nashville?

Brochure from Baptist Sunday School Board Church Architecture Department (Southern Baptist Archives)

“If the church was just beginning and had bought property, we would analyze the information they provided … and the goal for the first unit of space. Then we would recommend a plan that would meet their needs,” said Charles Businaro, an architect who worked 24 years in the Church Architecture Department.

“That would be a stock drawing. After that, we would work with the church. Before we did the plan, we would look at their property and do a master plan to see where the first unit and future units should be located. Prime space on the property was saved for future worship space and future educational space.”

The services available were so detailed that even a landscape architect was provided.

“We really tried to help the church see the validity of building educational space and going to two or three worship services in their smaller space,” Businaro explained. “Usually square-footage wise, the cost of worship space would be more expensive than for educational space. The Sunday school and educational space supported the worship space.”

Building plans from the Sunday School Board also showed churches how to make multiple use of the same spaces — often with folding walls that could divide worship spaces and fellowship spaces into smaller classrooms.

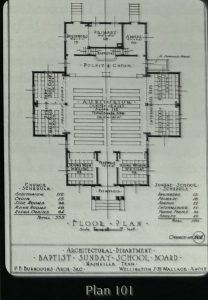

A basement fellowship hall that doubles as education space. (Southern Baptist Archives)

For churches with the space and the funding, separate education buildings were recommended that provided large assembly rooms surrounded by smaller classrooms. Throughout the majority of the 20th century, this model of an opening assembly followed by smaller group sessions in adjacent rooms was the ideal model for Sunday school departments of all ages.

“We wanted to have appropriate types of space for Sunday school,” Businaro said. “We knew that took 10 to 12 square feet per person for adults, 20 to 25 square feet for children. We had charts to work with on amounts of space.”

The Church Architecture Department worked closely with the Sunday School Department to implement the best practices being promoted nationwide in conferences and books.

“While we had the stock plans, lots of states still required churches to meet local building codes and often required a local architect to be involved in adapting our stock plans,” Businaro said. Thus, the Church Architecture Department began holding training sessions for architects across the country.

All this work was coordinated through state Baptist conventions, many of whom had their own church architecture departments that collaborated with the Sunday School Board.

Model of a church site plan created by Baptist Sunday School Board (Southern Baptist Archives)

Distinctive plans

The end result was not just efficiency of scale but also a landscape that made Southern Baptist churches easily recognizable. As mission work expanded into the West and Northwest, the recognizable buildings of the American South popped up from Phoenix to Boise.

What makes these buildings distinctive from other church structures is the relatively large amount of classroom space compared to worship space and the intentional staging of a first worship space that later was converted to a chapel or fellowship hall when a second worship space was built.

One of the most popular plans began with a chapel on one end of the property, which was followed by a ranch-style educational building adjacent. Ultimately, a larger sanctuary was built in the center of this site, with educational space spanning out like wings on either side, connected to the chapel at the end.

Basic church design plan from Baptist Sunday School Board (Southern Baptist Archives)

While the basic layouts stayed much the same, the outward forms and finishes changed with the times, running from classic Georgian style buildings with white steeples to mid-century modern buildings with colored glass and sharp angles.

At its peak, the Church Architecture Department employed about 35 people and divided its work into four regions of the country. Businaro said he alone worked with about 50 churches a year.

Multiplied over the years, tens of thousands of SBC churches got their building plans from Nashville. And it wasn’t just building plans; the Sunday School Board also provided design services for exterior signs, steeples and even parsonages.

Booklet promoting designs for church parsonages. (Southern Baptist Archives)

In 1955, the Sunday School Board published a 22-page brochure titled “Home for the Pastor.” Floor plans for 14 styles of parsonages were offered, ranging from a 1,595-square-foot “economical style” to a 3,100-square-foot “contemporary” plan.

Most often, these homes for pastors and their families were built adjacent to the church. Sunday School Board literature extolled the parsonages as a source of local pride for a church, a convenience for the pastor’s family and a potential for additional fundraising.

Origin story

How all this got started is recounted in an essay written by Bill Sumners, former director of the Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives. His essay was published in a 2015 Journal of Florida Baptist Heritage devoted to church architecture.

The story begins with establishment of the Sunday School Board in 1891.

By the early 20th century, the board was promoting efficiency and standards — a movement to create “standard” Sunday School and Training Union programs in churches nationwide.

“As the board ventured into grading and departmentalization for religious education, the demand for adequate buildings and space increased,” Sumners wrote. “Places of worship needed to be designed and built to meet the new demands of the 20th century church. Most churches, both city and rural, erected buildings with an emphasis on corporate worship, but had little space for Christian education and Bible study. Older churches needed to be remodeled to fit this new standard for efficiency and productivity.”

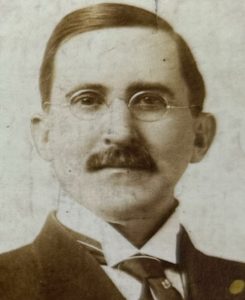

Harvey Beauchamp

Harvey Beauchamp became a pioneer in this work, guided by his interest in helping churches develop graded Sunday schools with trained teachers.

“He also knew that successful schools needed adequate space, placing great emphasis on adequate church buildings,” Sumners said. “He devoted extensive time helping churches build and remodel. He sought to provide adequate facilities for both teaching and training but had a high regard for beauty.”

In 1911, Beauchamp wrote The Graded Sunday School, in which he offered suggestions and designs for church structures.

“He added information about lighting, ventilation and heating,” Sumners noted. “He cautioned churches not to debase the Sunday school by relegating it to a side room or basement. Beauchamp provided plans and layouts for both large and small churches and Sunday schools. He closed his chapter with information on equipment and furnishings.”

The next champion for church architecture among Southern Baptists was P.E. Burroughs who, like Beauchamp was a native Texan. Burroughs had the distinction of attending Baylor University with such Baptist legends as L.R. Scarborough and Pat Neff. His ministerial ordination council included R.C. Burleson, B.H. Carroll and George W. Truett.

In 1906, he was called as pastor of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, which at the time had the largest Sunday school in Tarrant County Baptist Association.

P.E. Burroughs (Southern Baptist Archives)

From there, J.M. Frost hired him to work at the Sunday School Board in Nashville and ultimately he became the first head of the new Architecture Department in 1917.

In his book Church and Sunday School Buildings, Burroughs “used his experience as a pastor and educator to provide a comprehensive guide book to building and remodeling a church for multi-purposes,” Sumners wrote. “The book was full of architectural renderings, design plans, and photographs. The author credited numerous architects who drafted the design plans for the books.”

In 1923, Burroughs wrote A Complete Guide to Church Building in which he said: “With our increase in wealth, with our diffusion of architectural taste, and above all, with our enlightened appreciation of religion as a prime factor in our civilization, is it too much to expect our churches will more and more in their buildings seek beauty and impressiveness, as well as practical utility?”

By 1924, the Architecture Department had assisted 4,631 churches since its inception in 1917, Sumners said.

The Great Depression sidelined all this work for a time, but it came back to life in the mid-1930s as the SBC picked up its own growth rate.

“From 1916 to 1936, Sunday school enrollment had shown a gain of 1,347,229 and had moved to a well-designed graded Sunday school,” Sumners wrote. “Burroughs estimated that 90% of Southern Baptist churches had problems with lack of space, or dealing with poorly designed space, to meet the needs of Sunday school. If the church was to reach people for Christ, the facilities needed to be functional and inviting for the new age of people.”

Burroughs continued writing books about church buildings and capital campaigns and Sunday school growth. He was promoted to another role in 1940 and retired in 1943.

Collection of Burroughs books from Southern Baptist Archives

“What was the impact of this department and Prince Burroughs on the face of Southern Baptist architecture?” Sumners asked. “A brief survey of the booklets and books produced by the department and a view of Southern Baptist churches illustrate the significant imprint of Burroughs and the department. The images found in these publications are found across the tapestry of the Southern Baptist landscape. This is certainly true among rural churches that depended on the assistance of the Church Architecture Department and the recommended suggestions.”

Current-day resources

The work started by Beauchamp and Burroughs rode a high wave into most of the 20th century, but by the end of the century the landscape was changing.

Not only was church attendance declining nationwide and church buildings closing, the majority of growth was trending toward megachurches that have the money and access to other architectural services.

In 2013, Lifeway Christian Resources — successor to the Baptist Sunday School Board — began a partnership with Visioneering Studios, a nationwide design-build firm. A 2018 Baptist Press story said Visioneering Studios at the time was working with churches in four states.

The Institute for Sacred Architecture explains: “In the two decades after World War II, American Christians built an unprecedented number of churches as a postwar baby boom and suburban expansion created tremendous demand for new houses of worship. The trend began in 1947, when Americans spent $126 million on church construction, and peaked in 1965 at some $1.2 billion.”

In the 21st century, construction spending on religious facilities hit a record low of $3 billion in June 2021, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s a 66% decline from the $8.8 billion record high in August 2003.

Cover image from a Baptist Sunday School Board brochure on church architecture (Southern Baptist Archives)

While some churches are building or remodeling, more and more churches are struggling to know what to do with unused space and unused buildings.

The Lake Institute on Faith and Giving reports that between 1% and 2% of U.S. churches are closing their doors every year. That’s somewhere between 75 and 150 congregations closing every week.

Rick Reinhard

New industries have arisen that specialize in converting church properties into new uses. One leader in that movement is Richard Reinhard, who is an occasional columnist for BNG.

“Church boards often want to hang on to properties until the bitter end,” he told a National Association of Realtors publication. “But they tend not to reinvest in the property in the meantime. That ends up being a problem for communities, because they don’t want buildings that are falling down.”

And just as the Sunday School Board decades ago developed formulas for how much space a church needs for every type of classroom, Reinhard has his own formulas today.

Church property costs $7 to $10 per square foot annually to operate, which can mean $70,000 to $100,000 for a modest 10,000-square-foot property, he says.

With declining budgets, that means more and more of those recognizable Southern Baptist church buildings in every village and town across America could begin to look like an outgrown McDonald’s or Pizza Hut.

Those in the know will drive by and remark, “That sure looks like it used to be a Southern Baptist church.”

Editor’s note: Research for this article was greatly aided by the staff of the Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives in Nashville. Their collection includes documents, photographs and blueprints from the Church Architecture Department.