Contrary to popular opinion, young people of color have not abandoned religious belief and in fact are praying, meditating, reading Scripture and building sacred fellowship on their own terms, youth ministry expert Megan DeWald said.

Megan DeWald

This reality escapes or frightens many faith leaders and congregations, said DeWald, director of the Institute for Youth Ministry at Princeton Theological Seminary, who spoke during an Instagram forum hosted by the Springtide Research Institute.

“Young people aren’t waiting on the church anymore. They’re doing it themselves. They’re creating communities of belonging,” she said. “They’re engaging in faith-based and spiritually grounded practices, including acts of justice and peacemaking, which are central to how they understand their faith to be lived out in the world. And they are doing it without the stamp of approval from churches.”

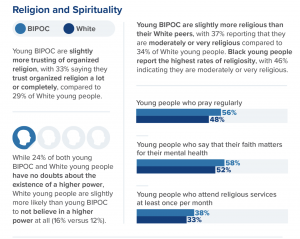

The webinar was held to discuss the institute’s February report, “Navigating Injustice: A Closer Look at Race, Faith and Mental Health.” The study found that young BIPOC — Black, indigenous and people of color — are slightly more religious and enjoy better mental health than their white Generation Z peers.

DeWald and BIPOC Research Fellow Cassandra Ogbevire delved into the study’s implications for churches and specifically for parents and youth ministers.

Many churches are missing an enormous opportunity to connect with this demographic by failing to see the authenticity of the religious focus and practices of youth and young adults of color, DeWald said. “Leaders of churches and Christian communities most often miss the boat when they only confer theological legitimacy on the faith and spiritual practices that are happening inside the four walls of the church or in church-sponsored activities of some kind.”

Clergy must abandon the notion that young people of color need formal ministries to understand their own spiritual formation and challenges, she said. “Gen Z is acutely aware of the existential threats that are facing their generation. … Gen Z folks know about school shootings and other forms of gun violence that impact their lives and their communities. They’re deeply aware of the existential threats posed by climate change, by racial injustice, by the attempted eradication of trans and nonbinary identities — and this list goes on and on.”

Further still, the generation is keenly aware the church often has been either silent or hostile on these issues, DeWald added.

“They are so wrapped up in the narrative of decline, and their fears around that, that the church gives off this weird and desperate energy.”

That’s made worse when congregations make awkward overtures to young people, she said. “Churches tend to often fall into this wishy-washy ground where they are so wrapped up in the narrative of decline, and their fears around that, that the church gives off this weird and desperate energy for the presence of young people in their midst. It can be off-putting and suspicious to young people.”

Many churches also have designed youth ministry programs based on 1980s and 1990s models that do not take any of these modern realities into account, DeWald said. “It’s this professionalization of the youth ministry landscape that gives parents and caregivers this illusion that just dropping your kids off at church — into the hands of the professionals — should result in some kind of lifelong, faithful Christian discipleship.”

Religious communities must see that formation for young people of color happens in a relational way that can be incorporated into youth ministry, DeWald said. “It’s really important for youth ministry to be a place that equips and empowers parents and caregivers so they understand themselves as the transmitters of faith.”

Religious communities must see that formation for young people of color happens in a relational way that can be incorporated into youth ministry, DeWald said. “It’s really important for youth ministry to be a place that equips and empowers parents and caregivers so they understand themselves as the transmitters of faith.”

One of the most surprising findings in the Springtide study is the connection young people of color see between their faith and ethnic identity, Ogbevire said.

“Gen Z BIPOC are not just subscribing to Christianity, for example, because it’s tradition. It’s because this particular religion has given them spiritual tools such as prayer, meditation and Scripture to navigate racial oppression and affirm their cultural identity,” she said. “They’re active ethnic culture has shaped how they think about and experience religious concepts like God, prayer, justice and different ritual practices.”

Their disconnect from institutions of faith comes in part when congregations deny the importance of race, culture or gender identity as issues of spiritual importance, Ogbevire said.

“That leads us to this whole concept of spiritual bypassing — people just avoiding talking about race. People avoiding talking about social injustice. It’s the guise of using your spiritual beliefs because you don’t want to engage with the discomfort,” she said. “This whole concept that ‘There is no color. We are all one. Talking about racism is divisive. Let’s just focus on God,’ right? And I think something that we need to be mindful of about spiritual bypassing is that it robs individuals and faith communities of the opportunity for spiritual growth.”

Related articles:

What absurdism and a parody conspiracy theory tell us about why Gen Z is sleeping in on Sundays | Analysis by Laura Ellis

Study finds racial and ethnic identity plays a role in mental health of Gen Z