Prowling through the sleeping Abbey of Gethsemani on a “Fire Watch” July 4, 1952, Thomas Merton wrote in his journal, later published as The Sign of Jonas:

Prowling through the sleeping Abbey of Gethsemani on a “Fire Watch” July 4, 1952, Thomas Merton wrote in his journal, later published as The Sign of Jonas:

And now my whole being breathes the wind which blows through the belfry, and my hand is on the door through which I see the heavens. The door swings out upon a vast sea of darkness and of prayer. Will it come like this, the moment of my death? Will You open a door upon the great forest and set my feet upon a ladder under the moon, and take me out among the stars?

On Dec. 10, 1968, in Bangkok, Thailand, Merton ended a lecture to religious leaders noting:

And I believe that by openness to Buddhism, to Hinduism, and to these great Asian traditions, we stand a wonderful chance of learning more about the potentiality of our own traditions, because they have gone, from the natural point of view, so much deeper into this than we have. The combination of the natural techniques and graces and other things that have been manifested in Asia and the Christian liberty of the gospel should bring us all at last to that full and transcendent liberty which is beyond mere cultural differences and mere externals—and mere this or that.

Then, in words that captured the last of many ironies scattered across his life, Merton commented: “I will conclude on that note. I believe the plan is to have all the questions for this morning’s lectures this evening at the panel. So I will disappear.”

And disappear he did. Fifty years ago this December, death found Thomas Merton—Father Louis to his Trappist brothers—not in the “great forest” or the cloistered fortress of Kentucky’s Gethsemani Abbey but in the teeming, Buddhist-dominated city of Bangkok. It came, not with the dignity of a monastic opus dei, but in a freak accident, electrocuting the life out of one of the 20th century’s most formative and formidable religious sages. (Some current research challenges the circumstances of his death.)

“Merton’s appeal is multi-faceted and complex, then and now.”

In A Documentary History of Religion in America since 1865, Edwin S. Gaustad noted that, “No twentieth-century American monastic attracted more attention than Thomas Merton (1915-1968), a member of the Reformed Cistercians of the Strict Observance, or Trappists.” In a Cross Currents essay 1999/2000, Jewish writer Shaul Magid observed:

Thomas Merton’s popularity in America remains peculiar. . . . Many of his avid readers are not sure whether he was a voice from the past or from the future, a voice to return or a call to renew. In many ways Merton served as the spiritual conscience of late twentieth-century America, gently teaching with his life and letters the substantive difference between religion and spirituality.

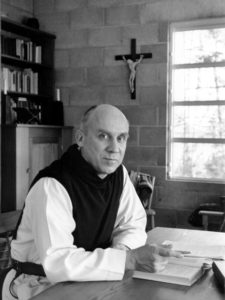

Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton remains an anomaly in American Catholic, indeed spiritual, life. Some see him as perhaps America’s best-known representative of monastic vocation, an immensely popular spiritual guide, grounded in Catholic theology and Trappist tradition. Others understand him as the harbinger of a new spiritual pluralism, freely exploring complementary and contradictory traditions, offering a hopeful progressivism in a Church now plagued by scandal, decline and ecclesiastical retrenchment. In the 50th year since his death, religious communities across the interfaith spectrum continue to need his words and his witness, desperately.

That Merton, born “on the last day of January 1915, … in a year of a great war, and down in the shadow of some French mountains on the borders of Spain,” should die so far from his monastic home is one of multiple ironies that characterize the life of this amazing individual. In some sense, he was a man of the world, engaging life at its depths from the very beginning. His artist-parents carted him and his younger brother John Paul from France to England and then America where both father and mother died before their sons reached adulthood.

As described in his best-selling memoir, The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton’s early “worldliness” led to poor grades and dismissal from Cambridge University, then took him to Columbia University where he thrived on literature and philosophy, cigarettes and night life. A gifted teacher and literary, he was, by his own confession, “a true child of the modern world, completely tangled up in petty and useless concerns with myself.”

Ultimately, Merton found himself by withdrawing from that world in 1942, entering the Trappist order that provided community, solitude, spiritual sustenance and an opportunity to reflect and write. And did he write! Ironically, the literature he produced from that cloistered environment became the source of an extensive international reputation, a phenomenon neither he nor his monastic superiors anticipated.

Merton’s appeal is multi-faceted and complex, then and now. Unashamedly Christian, his literary skills and spiritual insights continue to impact persons of varied faiths and of no discernable faith at all. An articulate guide to the solitary life, he also sought to confront the world, addressing the challenges of his own day including the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, peace and nuclear proliferation.

Drawn to faith by the spiritual and liturgical traditions of Catholicism, Merton died at the very moment when he was forging spiritual exploration with Buddhists, anticipating interfaith dialogue amid religious pluralism. His extensive literary corpus (Merton seems never to have had an unpublished thought) offers guidance in meditation, contemplation, self-examination and spiritual discipline for individuals inside and outside the Catholic Church. Ironically, he now represents certain classic monastic ideals at a time when almost no one (at least in the West) wants to become a monk.

“Merton’s words, like the Word made flesh, haunt us yet. These days, we need that kind of haunting.”

To read Thomas Merton is often to be captivated by his use of words, his spiritual insights and his quest for the mysteries of life and death, faith, hope and love. Sometimes his essays are so incredibly profound that you return to them again and again; sometimes his ideas are so obscure, convoluted or frightening that you revisit them at your peril.

From the The Seven Storey Mountain to his final thoughts in The Asian Journal, Merton’s life is in full review, ever a struggle with sin and salvation, doubt and celebration. In certain works, he is too “Catholic” for many moderns; in others he seems too “Protestant” or “Secular” for many contemporary Catholics.

What draws us back to Merton 50 years after his death is his haunting ability to unite the transcendent and the worldly, the inner and outer life with wondrous prose, occasional poetry and enduring spiritual insight.This call to prayer and action occurs throughout his writing, often as relevant now as when he wrote it over a half century ago. At Advent in this year of political, religious and cultural crisis, as racism deepens its hold on American life and faith, we need to hear his prophetic word from Raids on the Unspeakable:

Into this world, this demented inn, in which there is absolutely no room for Him at all, Christ has come uninvited. But because He cannot be at home in it, because He is out of place in it, and yet He must be in it, His place is with those who do not belong, who are rejected by power because they are regarded as weak, . . . tortured, exterminated. With those for whom there is no room, Christ is present in this world.

Thomas Merton’s words, like the Word made flesh, haunt us yet. These days, we need that kind of haunting.