By Bob Allen

Healing America’s racial rift will require changing not only hearts and minds but also systems that oppress racial minorities and the poor, said a speaker at a recent gathering of Baptists in Missouri focused on building peace and reconciliation.

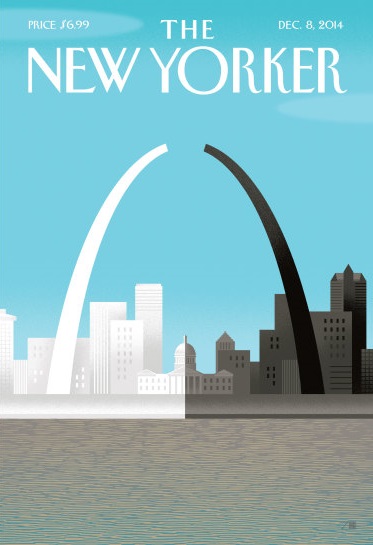

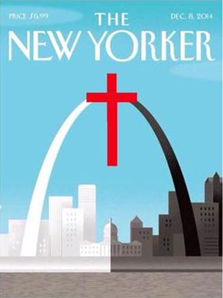

Brian Kaylor, communications and engagement leader for Churchnet, cited a New Yorker cover from last December depicting St. Louis with a “broken” Gateway Arch separated by shades of black and white. Someone “fixed” the image by superimposing a cross over the gap, and the image went viral over the Internet.

Brian Kaylor, communications and engagement leader for Churchnet, cited a New Yorker cover from last December depicting St. Louis with a “broken” Gateway Arch separated by shades of black and white. Someone “fixed” the image by superimposing a cross over the gap, and the image went viral over the Internet.

Speaking at the 13th Churchnet annual gathering April 24-25 in Jefferson City, Mo., Kaylor said the feel-good image embodies a problem within U.S. churches “that waters down the gospel to a privatized faith” concerned only with the afterlife.

Speaking at the 13th Churchnet annual gathering April 24-25 in Jefferson City, Mo., Kaylor said the feel-good image embodies a problem within U.S. churches “that waters down the gospel to a privatized faith” concerned only with the afterlife.

Addressing a theme of Share Hope: Building a Community of Peace and Reconciliation, Kaylor said one product of such a view is a “spiritualized, individualistic, colorblind faith” that assumes people could get along if they stopped worrying about the color of each other’s skin.

“The problem remains that while souls may not have a color, people and systems do,” Kaylor said. “The colorblind approach ultimately fails because it reduces racism down to merely interpersonal issues.”

Kaylor, a former communications professor at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., and author of three books, said reducing personal racism in the United States “would be great,” but doing just that would still leave structural racism in place.

“What colorblind people miss is that many laws create an unjust imbalance that particularly targets racial minorities or people with lower incomes,” Kaylor said. “As we learned in the Justice Department’s damning report on Ferguson — a report that led to several city officials losing their jobs — injustice thrives at systemic levels.”

Kaylor said “colorblindness” makes some Christians blind to systemic sins such as mass incarceration of African-American males, racial inequality in imposing the death penalty and preachers who peddle eternal life while people suffer in the shadows of their steeples.

“Surely our scriptures must have something to say about the fact that as you move from one ZIP code in Kansas City to another, the life expectancy drops 16 years,” Kaylor said, “or that as you move from one ZIP code in St. Louis to another, the life expectancy drops 18 years.”

Kaylor dismissed the notion that America is a “post-racial” society. He also was dubious about talk of a “post-Christian” culture, because it implies some sort of “Christian” past.

Kaylor dismissed the notion that America is a “post-racial” society. He also was dubious about talk of a “post-Christian” culture, because it implies some sort of “Christian” past.

“If we really are a post-Christian society, the years of 1957 and ‘58 would likely be nominated by many as that golden era when we existed as a Christian society,” Kaylor said. Back then, Kaylor said, Clarence Jordan, founder of Koinonia Farms and author of the Cotton Patch Gospels, wrote upon confronting urban black poverty in Louisville, Ky., during his time at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, “No, America isn’t Christian yet.”

Kaylor said the same is true today. “No, America isn’t Christian yet,” he said. “We don’t live in a post-Christian society, but I hope we still live in a pre-Christian one.”

Churchnet is a network providing resources to Baptist churches founded in 2002 as the Baptist General Convention of Missouri. Breakout sessions at the 2015 annual meeting featured titles including “Worship that Advances Peace and Reconciliation,” “Understanding Racial Issues from a Historical Perspective,” “An Introduction to a Conversation on Race” and a screening of Beneath the Skin, a documentary on Baptists and racism produced by the Baptist Center for Ethics.