Wayne Flynt is a Baptist minister whose calling frequently lands him in controversy.

“My role is to move the Kingdom of God one step closer, day by day,” says Flynt, 78, an acclaimed author and teacher on Alabama politics, Southern history and religion. He is an emeritus professor at Auburn University.

The native Alabaman says he felt that divine nudging as a teenager. He began to find his voice during the Civil Rights era by calling out the hypocrisy of a Southern culture that claimed Christ but seethed with racism.

Liberty University President Jerry Falwell Jr., right, has openly and enthusiastically endorsed the presidency of Donald Trump. A religion scholar said some evangelicals are desperate for help from Trump to save their dying churches. (Photo/The White House)

Nowadays Flynt’s ministry includes pointing out the way religious conservatives idolize, even worship, Donald Trump.

“The fundamental problem with Trump, for most white evangelicals, is that he is a messianic figure with feet of clay up to his armpits,” says Flynt, a long-time member and Sunday school teacher at Auburn First Baptist Church.

Illuminating contradictions between Christian belief and practice is Flynt’s bread and butter. It’s a role for which he is well known across the state and region. His critiques are delivered in op-ed pieces, speeches, sermons and lectures to all manner of audiences.

His profile has been on the rise since religious conservatives helped send Trump to the White House. When it comes to the president, he pulls no punches.

“He is the worst sort of narcissist, the worst hedonist in American public life, the worst materialist; he has spent all his life building bigger barns,” Flynt says. “He is a serial adulterer, a pathological liar. He is the worst, most flagrant liar in the history of American politics.”

Despite the both-barrels explosiveness of those words, Flynt speaks them in the calm, assuring tone of a chaplain comforting the sick.

‘A very personal level’

That gentle and humble demeanor is familiar to those who have worked and worshiped with him.

“We know him just as Wayne,” says Tripp Martin, pastor of Flynt’s home congregation, which is affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.

Tripp Martin

Viewing Flynt only for his criticism of Southern culture and Christianity overlooks his deep concern for social justice and those in poverty, Martin adds.

Flynt performs “a very ministerial role” as an academician, a public voice for justice and as a teacher and mentor, says his pastor. “He uses history to speak to the needs of today, which is where his ministry occurs outside the church.”

Flynt also provides a valuable pastoral presence within the congregation, Martin adds.

“He’s always sitting down with church members over coffee or lunch to hear their stories on a very personal level. He is one of those strong lay leaders who offers encouragement to the entire staff.”

‘The heart of the Hebrew Bible’

At the same time, Flynt knows when and how to take the gloves off, whether in writing, media interviews or speaking engagements.

Like in 2011, when The Birmingham News published a story including Flynt’s perspective on House Bill 56, a strict anti-immigrant measure that has since become state law.

“This is the most mean-spirited, hateful thing I have ever read,” Flynt states in the article.

Mean-spirited and racist because it claims migrant workers are taking jobs from Alabamans that, in truth, most Americans do not want, he explains to the newspaper.

The legislation also runs counter to the biblical imperative to show kindness to strangers, he adds.

“That message is right at the heart of the Hebrew Bible. Is that what we’re doing in Alabama? No, of course not.”

‘I slipped the bonds of my culture’

Flynt attributes his views to the Bible, which, as a Baptist growing up in a small-town, he was taught to read and take seriously.

“I was 14 or 15, and I was letting the Bible speak to me because that’s what my preachers were telling me to do.”

In its pages, however, he found a very different Jesus from the one proclaimed throughout much of the South.

“The more I read the Bible, the more I could not reconcile Southern culture with what I was reading in the Bible,” he recalls. “It was then I slipped the bonds of my culture.”

He went on to earn a bachelor’s degree from Howard College (which later became Samford). It was there, during the 1950s, that he began to encounter others who shared his views on scripture and race.

“I was hearing from my professors what I was hearing in the Bible,” he explains.

The experience convinced him of the potentially transformative nature of scripture. “The most powerful way to affect someone’s understanding of race and society and the cosmos is to read the Bible and take it seriously.”

He responded to a calling into ministry, though not in the traditional ways.

“I thought if I persisted with seminary, no one would call me as pastor – not with my ideas on race.”

And especially not in the South, where he wanted to stay.

He earned advanced degrees in American political history, with a focus on the South, at Florida State University. Being a scholar and author outside the church has enabled him to live into his calling.

“I can take the most advanced, outrageous positions on justice because my tenure depends on my teaching and my scholarship and not on what people think of me.”

‘Hang on to your day job’

He certainly wasn’t concerned with the Trump administration’s view of him in 2018 when he publicly scolded then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, a fellow Alabaman.

Sessions had quoted Romans 13:1 to justify the president’s policy of separating immigrant children from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border. Sessions’s claim that Trump’s anti-family policies are justified by scripture sparked a firestorm of criticism.

Jeff Sessions

Flynt responded with an open letter to Sessions published by The Birmingham News.

“Dear Attorney General Sessions,” the letter began. “Hang on to your day job at the Justice Department. I don’t believe you have much future as a theologian or Sunday school Bible study writer.”

Flynt then warned against quoting scripture out of context, especially when trying to justify a political position. The verse urging obedience to authorities, he noted, was once notoriously quoted to justify slavery.

Moral conscience must always supersede national law, he continued, adding that other verses in Paul’s letter to the Romans aren’t often quoted by conservative Christians these days. especially Romans 13:9 which forbids adultery.

“I bet you won’t quote that one to the BOSS!” Flynt wrote.

If a frightened, undocumented refugee carrying a toddler shows up in Auburn, Flynt declared, he would not report them to authorities but instead offer to help. “So will a LOT of other Auburnites.”

‘I wanted him to run for governor’

Descriptions of Flynt as fulfilling a prophetic role are not exaggerated, says church historian Bill Leonard, once an interim pastor at Auburn First Baptist.

Leonard says he was immediately impressed with Flynt’s inspired mixture of minister, social activist and historian.

“I wanted him to run for governor of Alabama because I thought he had the political savvy and the institutional and personal compassion” needed to govern justly, Leonard recalls.

Instead, Flynt has chosen to remain true to his mission of bringing biblical insight to issues of race, culture, politics, history and religion, Leonard says.

James Dunn and Bill Leonard following a Wake Forest University convocation service in 2012. Photo courtesy of Bill Leonard.

The scholar’s written works are prolific. They include a history of Alabama and accounts of women, governors and poor whites in the state. He also is author of works like Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie and Southern Religion and Christian Diversity in the Twentieth Century.

His academic achievements lend authority to his ministerial calling to speak truth to power, Leonard says. “He is in keeping with that very important tradition of Baptist progressivism, and especially Baptist progressivism in the South.”

Forerunners of Flynt’s ministry include 20th-century Baptists such as James Dunn, a champion of church-state separation and former leader of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, and Social Gospel theologian Walter Rauschenbusch, Leonard says. He can even be compared to Roger Williams, the 17th-century advocate for abolition and religious freedom.

“He is prophetic, yes, but also reasoned and deliberative in his approach,” Leonard says. “He does not hesitate to challenge Southern culture on a variety of issues: race, segregation or religious liberty.”

Flynt also is an inspiration to progressive Baptists in an age when the word ‘Baptist’ has a negative connotation for many Americans.

“He has inspired many people to remain or to accept Baptist identity because of the way he both articulates and lives it,” Leonard says.

‘Process God the way you want to’

One of the places where Flynt articulates and lives his faith is the Sunday school class he teaches at Auburn First Baptist Church.

No biblical topic is off limits. Passages some Christians may want to avoid are routinely examined.

During a Sunday morning session this summer, Flynt presses the adult participants to consider God’s apparent command to the Hebrews, in the Book of Joshua, to kill every man, woman, child and animal in Jericho following their defeat of the city.

Flynt presses the question: Did God desire genocide or was this the Hebrews’ understanding of God at that time in their history?

Responses come flying in. Flynt handles each one calmly and without judgment.

He asks class members for their own conceptions of Christ. They offer words like loving, forgiving, compassionate, gentle, teacher, savior, friend.

Another adds “troublemaker” to the list. Flynt agrees, noting that Jesus was considered an agitator because he introduced a conception of God contrary to prevailing notion of his time.

There is nothing wrong with challenging and debating any concept in scripture, he says.

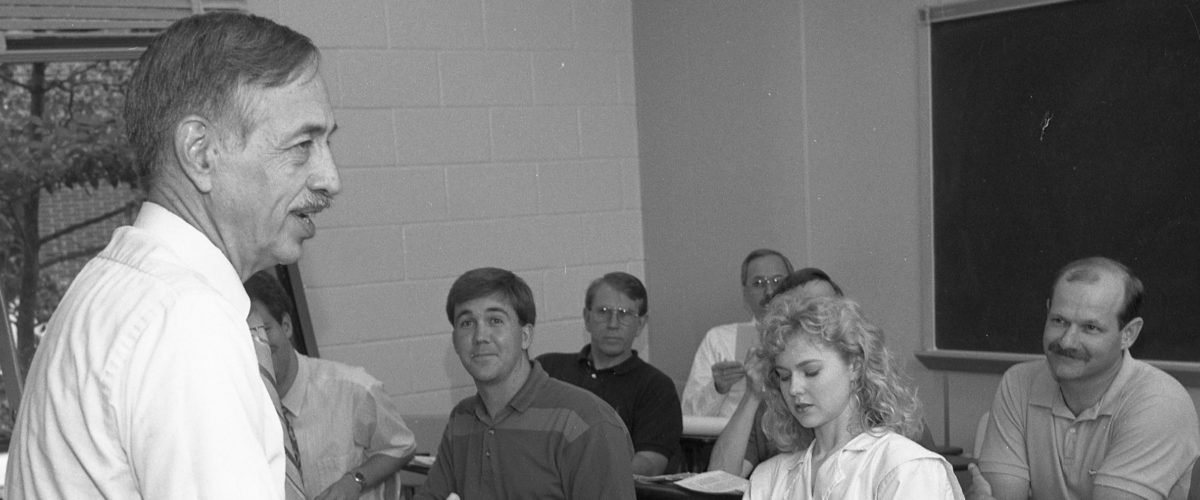

Wayne Flynt takes a question during the Sunday school class he leads at Auburn First Baptist Church.

“You have the option as Baptists to choose how you want to interpret that,” he explains. “We perceive God in different ways. The ‘priesthood of believers’ means you process God the way you want to.”

Several class members push back during the discussion. That’s also key to the faith, Flynt says.

“We are Baptists because we allow each other to exist in that framework.”

It’s an approach to interpreting scripture that inspires non-Baptists, too.

In an interview, Connie and David Rosenblatt eagerly share that the tension encouraged by Flynt has revolutionized their faith.

“I grew up Baptist,” says Connie, a Methodist who attends Flynt’s class. “It was ‘do it and don’t ask why.’”

Her husband is Jewish. Flynt ties together Hebrew and Christian scriptures in a way that brings Judaism to life for him.

“He not only cites the biblical references but also what was going on at the time when this was being written,” David says. “He puts things into context from the Old Testament that I didn’t know about or understand because I didn’t have much Jewish education.”

The couple has known Flynt for many years through Auburn University, where David was also a professor. They started attending his Sunday school class a few years ago after hearing a lot of buzz about it.

Connie says the gatherings have given her a new respect for Baptists, helped her embrace scripture and re-energized her Methodist faith: “This is the first time in my life I have heard things that actually made sense.”

It’s brought the couple deeper mutual respect, too.

“Dr. Flynt’s class has brought us together so much more in our different religious backgrounds,” says Connie.

‘No more Matthew 25’

It may sound radical to some, Flynt says, but it’s just an outgrowth of reading scripture.

“I consider myself a biblicist. I read it every day.”

Which brings him back to the president and the lust for political power he says is trumping biblical values among many white evangelicals.

Flynt recalls a time when conservative Christians, especially in the South, would never have endorsed a politician who is divorced – even once. But that steadily shifted as white evangelical ministers started getting divorces. “Then it switched to same-sex marriage and abortion” as top moral concerns.

Christ has a lot to say about divorce, he adds. “But show me the passages where Jesus said anything about same-sex marriage and abortion. Well, there are none.”

Similarly, there was a time when Protestant Christians, especially Baptists, staunchly supported the separation of church and state. Their ancestors’ experience in Europe demanded it. But that changed as they tasted political power and influence.

“Once they become insiders and dominant, like Alabama Baptists have, they try to impose their theology on everybody else,” Flynt says. “They want to make (the United States) a theocracy, not a democracy.”

Also gone from their witness is anything approximating Christ’s commands to support the poor and to welcome the stranger, Flynt continues. Political necessity for some has made those values secondary, at best.

“There’s no more Matthew 25,” he says of the passage about visiting the sick and imprisoned, helping the poor, hungry and thirsty, and welcoming the stranger.

Still, Flynt remains “resolutely upbeat” about the future. He sees white evangelical support of Trump less about endorsement of a demagogue and more about rejection of a government they feel has let them down.

Besides, progress has always come gradually in the church. Slowly it came around on slavery and Civil Rights, on labor and fair wages.

For Flynt, pessimism has no place in a Christian life thoroughly steeped in Scripture. He recommends white evangelicals give it a try.

“Instead of preaching to everybody and talking about how bad (former President Barack) Obama and Hillary (Clinton) are, just spend a year reading the Bible quietly to yourself,” he suggests.

If nothing else, he says, it would reduce the influence of cultural and politics on the church.

“I can’t think of anybody who was less influenced by his environment than Jesus.”