With memories of the 9/11 terrorist attacks still raw, Charles Kimball, a professor, Baptist minister and expert analyst on the Middle East, drew on three decades of experience to write a book released in 2002 about why people do bad things in the name of religion.

In When Religion Becomes Evil, Kimball, at the time a professor at Wake Forest University, identified five warning signs common to all religions – absolute truth claims, blind obedience, the impulse to establish an “ideal” time, belief that the end justifies the means and the declaration of holy war – and gave advice about how to recover what is best and healthy in all religions.

Charles Kimball

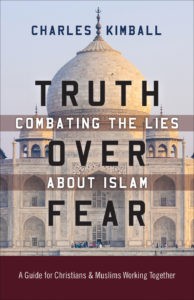

In his latest book, Truth over Fear: Combating the Lies about Islam, Kimball explores a new development in Christian-Muslim relations – the mainstreaming of Islamophobia as a pathway to political success.

Now presidential professor and chair of religious studies at the University of Oklahoma, Kimball discussed ways Christians and Muslims can work together in this Q&A about the recent release of the new 180-page paperback published by Westminster John Knox Press.

Why did you write this book?

The 21st century may well be defined by interfaith relationships. The most dangerous and widespread flashpoints center on relationships between adherents of the world’s two largest religious communities: Christians and Muslims.

This book grows out of more than 40 years of work focused on my vocation with a teaching ministry and constructive interfaith cooperation in the U.S. and the Middle East. Speaking in more than 500 colleges, universities, seminaries, divinity schools, churches, mosques, synagogues, civic organizations, etc., I have a clear sense of the kinds of questions and concerns about Islam that foster widespread fear in the West.

While there remains a lot of goodwill, a large majority – including a large majority of Christian clergy – still lack the resources to address growing Islamophobia or pursue constructive programs with Muslims (and others) in their local setting.

This book seeks to address this urgent need by providing a new paradigm for how Christians and others of goodwill can better understand Islam as most Muslims live out their faith. And, it offers an accessible guide for positive initiatives individuals and congregations can take to work toward a more healthy future between Christians and Muslims.

Is America Islamophobic?

Sadly, in 2019 all evidence suggests the answer is “Yes.”

Christians and Muslims have traveled a long, circuitous, and often bumpy road together for more than 1,400 years. There has been far more cooperation in lands with Muslim majorities than most people in the West perceive.

The roots of mistrust, misunderstanding and fear of Islam run deep in Europe and North America. Many developments in the tumultuous events of the 20th century world of nation-states – particularly in the decades since the 1979 revolution in Iran and the emergence of militant Muslim non-state groups – have led to a clear rise in the growing, generic fear of Islam as a religion that is somehow inherently violent and menacing.

What are the lies that people tell about Islam?

There are many, but the most prominent ones include the following: the true goal of all Muslims is world domination; Muslims want to impose Sharia (Islamic Law) on all people in the society; Sharia is rigidly fixed and it requires a harsh, corporal system of punishments for criminal and moral infractions; the Qur’an tells Muslims to kill Jews and Christians; Allah is a false god or demonic spirit; Islam is completely incompatible with democracy; and women in Islam are all oppressed.

There is another “lie” about Islam that also needs to be addressed. More than a few Muslims (and others) say “Islam means peace” and suggest that this ends the discussion. Islam is not monolithic any more than Christianity or any other major world religion. One cannot simply dismiss anyone or group claiming inspiration from your religion and behaving in ways that appear to contradict the most fundamental teachings. Militant Muslim extremists are part of the picture just as the KKK, Crusaders and the untold millions of Christians who have persecuted Jews and other Christians down through the centuries.

There is another “lie” about Islam that also needs to be addressed. More than a few Muslims (and others) say “Islam means peace” and suggest that this ends the discussion. Islam is not monolithic any more than Christianity or any other major world religion. One cannot simply dismiss anyone or group claiming inspiration from your religion and behaving in ways that appear to contradict the most fundamental teachings. Militant Muslim extremists are part of the picture just as the KKK, Crusaders and the untold millions of Christians who have persecuted Jews and other Christians down through the centuries.

Here is the problem: Most people tend to think of their own religion in the “ideal” and everyone else’s religion in terms of the flawed lived reality one observes in the behavior of adherents. Reducing the religious traditions of hundreds of millions of people to a caricature or stereotypical image is, by definition, misleading.

Who is stoking these fears, and why?

Many politicians, preachers and self-appointed pundits fuel Islamophobia on a daily basis. The book cites prominent examples to illustrate the point. Whether or not leaders are sincere or cynical, many appear to believe that stoking fear about Islam and Muslims serves their purpose(s).

Ramping up fear and hostility toward Muslims has real-world consequences as public harassment of individuals and families as well as threats and malicious attacks on mosques continue to rise. Recall and consider the implications of President Trump’s highly visible declaration in the summer of 2019 that the two Muslim women elected to the U.S. House of Representatives should “go back” to where they came from. A sickening reminder of the real-world consequences of Islamophobia occurred in March of 2019 when more than 50 Muslims were slaughtered as they gathered for prayer at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand.

What should Christians make of attempts by state legislatures to prohibit the practice of “Sharia law?”

My home state of Oklahoma was the first state to take an initiative to “ban” Sharia with a hastily prepared referendum placed on the November 2010 ballot. (Note: Many people refer to Sharia law, but this is redundant. Sharia means “Islamic law.”) Oklahomans voted strongly in favor of “banning Sharia and all other forms of international law” by a 70 percent majority.

Although this initiative was quickly struck down in federal court, the swell of support for the referendum was instructive: Most Oklahomans were fearful and clearly didn’t want Sharia coming across the Red River to somehow take over U.S. and state laws. Research and articles by journalists revealed quickly that almost no one who was in favor of the referendum could even define Sharia! People in my state – and in more than 20 states subsequently where similar measures have been proposed – were both fearful and uninformed.

The first step is education. In Truth over Fear, I devote attention to this issue, explaining how Islamic law is supposed to work in the life of faith for Muslims, how it is not static but always a “work in progress” as circumstances dictate the need for adaptation and changes.

I know hundreds of Muslims, and not one wishes to have Sharia be the law of the land here in the U.S. Christians should seek first to understand what Sharia represents, how it is supposed to work (in its many variations), and then speak to those who are pushing efforts to prohibit Sharia in their settings. Here is a great question to pose to Muslims in educational forums and/or Christian-Muslim dialogue programs in churches: What is Sharia, and how is it integrated into the life of faith from your perspective?

Is Islam a religion of peace?

Without question, this is how the vast majority of Muslims would characterize their religion. The term “Islam” literally means the religion of those (Muslims) who submit themselves to God and therefore are at peace. The root of the word is from the same Hebrew word for peace: Shalom (salam in Arabic). Of course, as with Christians, Muslims have not always lived up to the ideal they affirm.

The 21st century may well be defined by interfaith relationships. The most dangerous and widespread flashpoints center on relationships between adherents of the world’s two largest religious communities: Christians and Muslims.

Religion is complex, and we must always seek to understand what is happening and why, and how self-professing devout people justify behavior that is clearly at odds with what is at the heart of their religion. A little self-awareness and self-reflection among Christians helps make the point. As a close rabbi friend once put it to me bluntly: “While we Jews welcome and celebrate this new day in Jewish-Christian relations, it is still not easy. It comes against a large backdrop: Two thousand years of ‘Christian love’ is almost more than we Jews can bear!”

What can readers of your book do to advance “truth over fear?”

Reading the book is a significant first step, since it addresses and, hopefully, clarifies many of the issues that fuel the fear of Islam and Muslims. Perceiving the worldview, basic ritual-devotional practices and Islamic history as most Muslims do will demystify the world’s second-largest religion and elucidate ways Christians and Muslims have a great deal in common. The final two chapters of the book offer a contemporary framework and very practical guidance on how to pursue dialogue initiatives and cooperative work in communities.

Since a great deal of positive work has been done by leaders in the Vatican and among Protestant and Orthodox ecumenical organizations as well as many denominations, individuals and congregations don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Rather, it is possible to build on the educational programs and initiatives in community that have proven to work well. The foundation begins with education.

This book seeks to provide a good deal of that foundation. But, the most effective form of education comes through personal encounter. The more people of faith and goodwill can do to help “humanize” the “other,” the less people will be susceptible to generic, monolithic images based on the behavior of extremists who get far too much attention.

The book is structured in a way that makes it work well for serious adult study programs in churches. The chapters are manageable in length and questions to facilitate discussion are included at the end of each chapter.